Debate on adoptionism

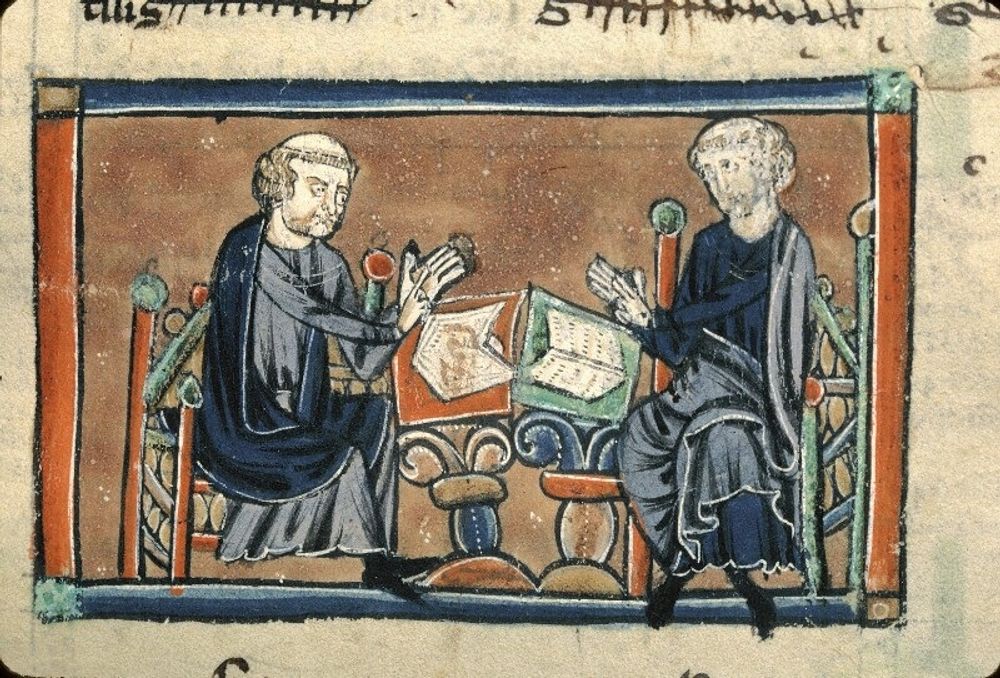

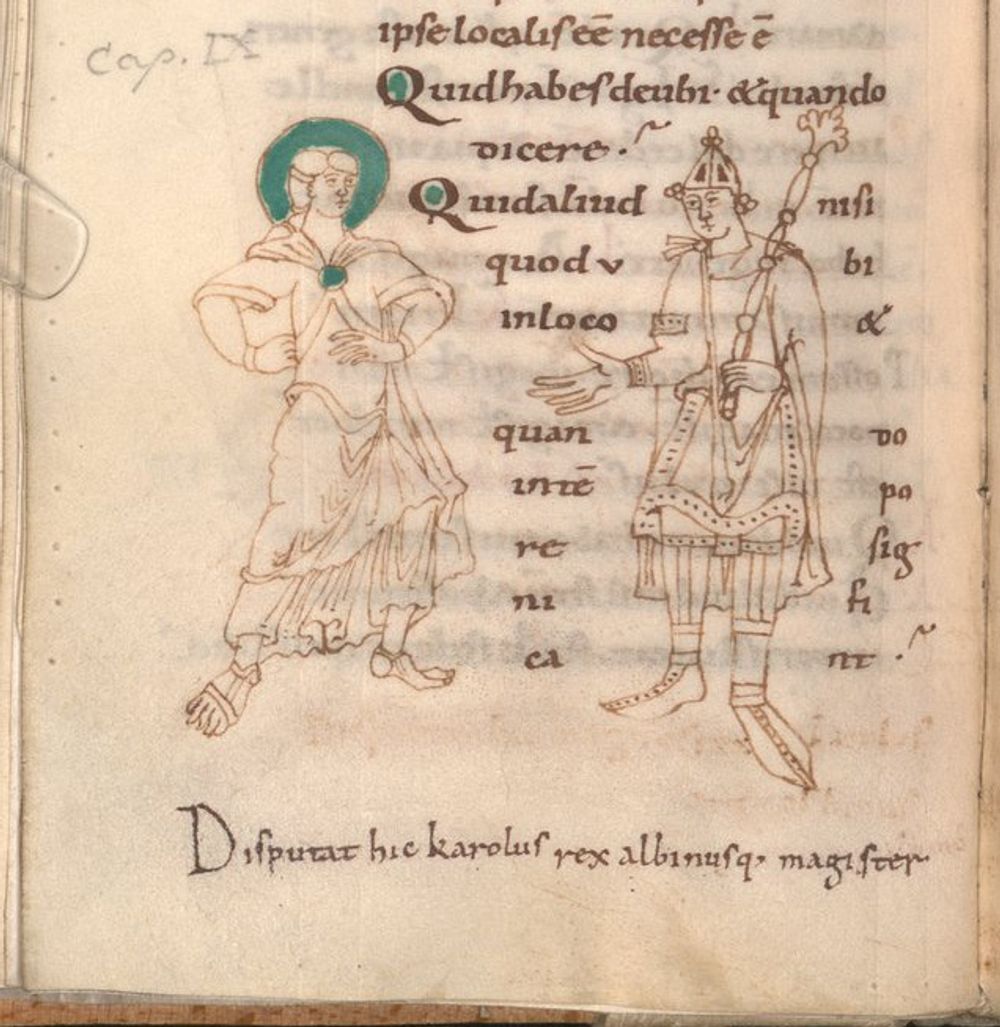

Disputing in front of the king1

In the last decade of the eighth century, Hispanic and Frankish scholars became embroiled in a dispute over the nature of Christ. The immediate cause of the conflict were the teachings of Bishop Elipand of Toledo (d. 808), who, according to his opponents, taught that Christ was the adopted son of God. Elipand was supported in his beliefs by Felix, bishop of Urgell (d. 818), whose influence reached across the Pyrenees, into the southern part of the Frankish kingdom. The Frankish king, Charlemagne, who considered himself a guardian of orthodoxy, felt the need to eradicate these, in his opinion, heretical beliefs and asked his most prominent courtiers to respond. This part of the exhibition addresses the role of texts in the debate on adoptionism. Did the participants learn their techniques of argumentation from studying treatises on rhetoric and dialectic, or did their knowledge derive from elsewhere?

Background of the controversy

The teaching of the Hispanic bishops is usually referred to as adoptionism, but this is actually a misnomer. The epithet goes back to a second-century sect, whose adherents held that God adopted the man Jesus as his son at the moment of his baptism. The label ‘adoptionism’ has been used since then to stigmatize different groups of Christians, who believed (or were thought to believe) that God the Father was superior to the Son.

A mosaic in the Arian baptistery in Ravenna, built around 500 by King Theoderic the Great, shows the baptism of Christ. The fact that Christ is depicted as a young and beardless man is meant to convey the Arian stance that Christ the Son is inferior to God the Father and not ‘of one substance’ with him.

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Baptism_of_Christ._Mosaic_in_Arian_Baptistry._Ravenna,_Italy.jpg

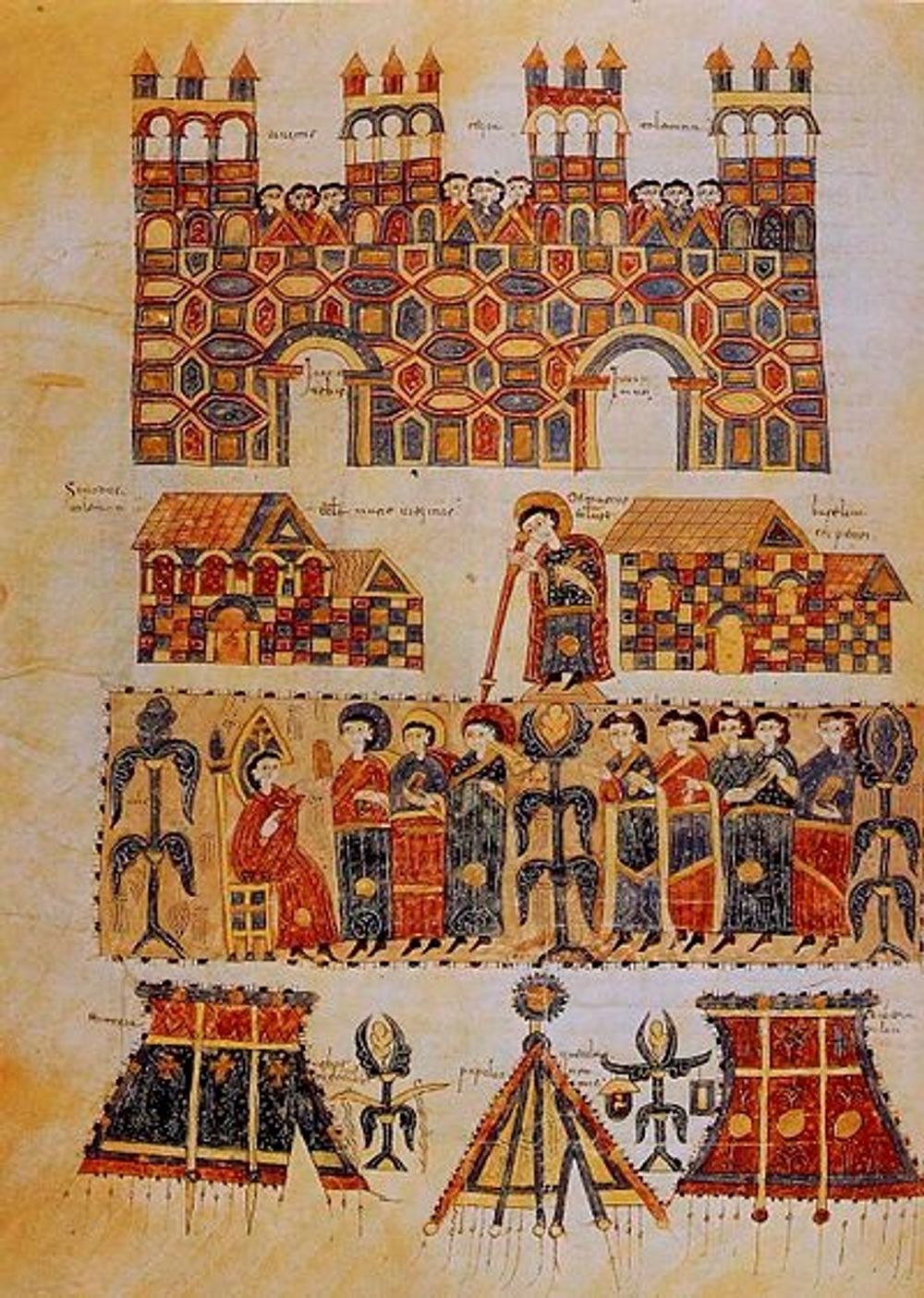

Elipand and Felix, however, did not teach that Christ was the adopted son of God. Rather, they held that Christ had adopted a human body when he became man. When they used the word ‘adopt’ they meant ‘accept’. Yet for the Franks, the very word adoptio or adoptivus set off alarm bells. It reminded them of heresies of the past. The conflict between the Frankish and Hispanic scholars ultimately sprang from a divergence between two cultural traditions. The theology and terminology of Elipand and Felix had grown from Hispanic conciliar traditions, in particular from the acts of the councils of Toledo.2 This manuscript from the tenth century (Codex Aemilianense, San Millán de la Cogolla, Biblioteca del Monasterio de El Escorial, D. I. I.) features an illustration that represents the Council of Toledo, or to be precise: it represents each Visigothic council held in Toledo in the sixth and seventh centuries.

https://www.wikiwand.com/es/Escritorio_de_San_Mill%C3%A1n

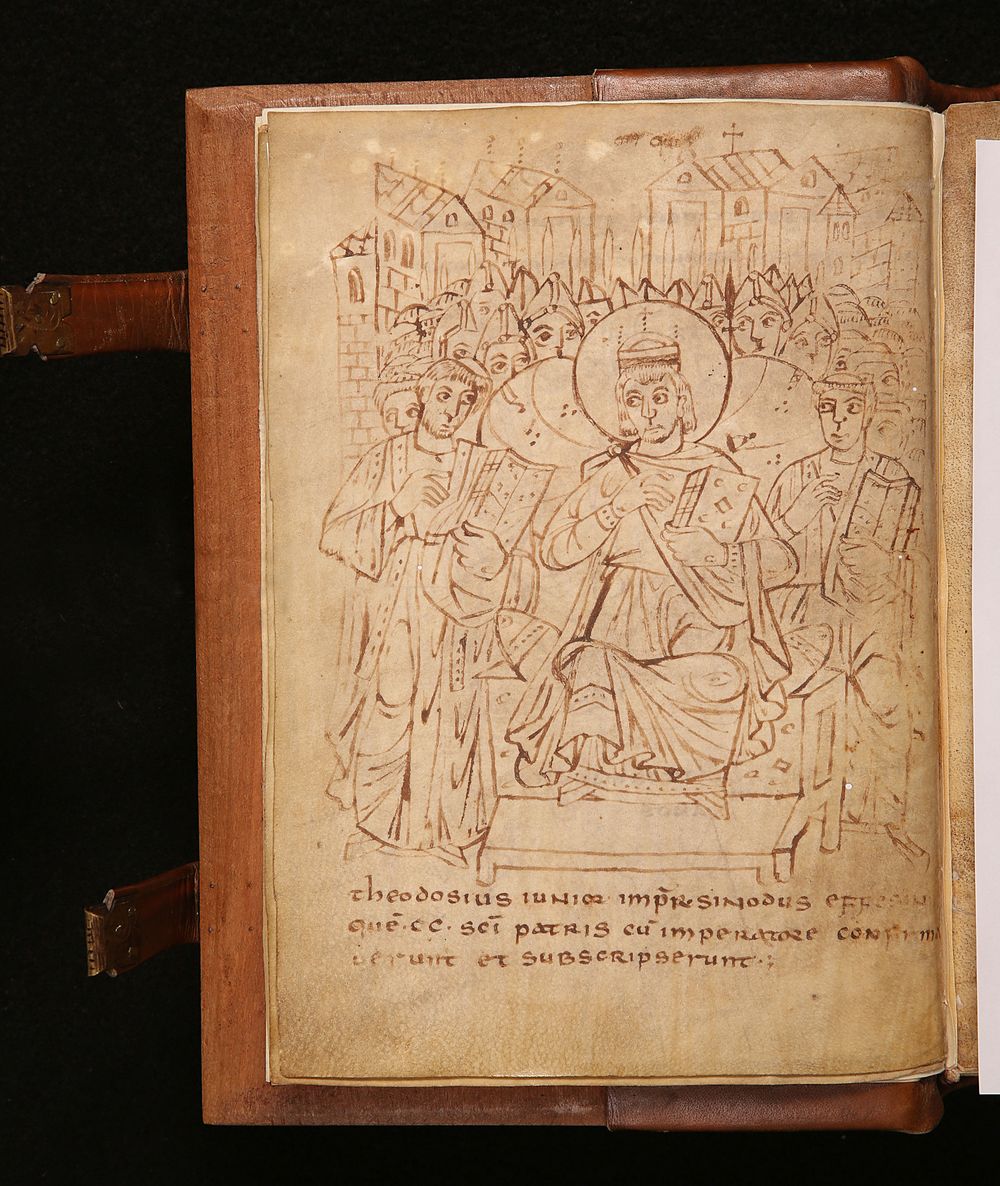

The terminology of the Franks, in turn, was shaped by the ecumenical councils of the East, in particular by the council of Ephesus of 431. At this council the doctrine of Nestorius of Alexandria (d. c. 450) was examined and condemned. Nestorius was another teacher who had been labelled an adoptionist. In the eyes of the Franks, Elipand and Felix were reviving Nestorius’ heresy. Here we see an illustration representing the Council of Ephesus of 431 that condemned Nestorius. The illustration is part of a series depicting the early ecumenical councils in a canon law collection (Biblioteca Capitolare of Vercelli, ms. 165) dated to the late eighth or early ninth century.

The Council of Ephesus produced a dossier of texts that provided a source of inspiration for the Frankish disputants. They borrowed arguments against Nestorius from this dossier to combat their Hispanic opponents. Nestorius had made use of the language of Aristotle’s categories to define his doctrine. He had argued that Christ had two natures (ousiae), human and divine, which corresponded with two masks (personae). Since Frankish scholars interpreted the teaching of their Hispanic opponents through the lens of Nestorius’ teaching, Aristotelian language and logic also resonated in the eight-century debate on adoptionism.

The debate

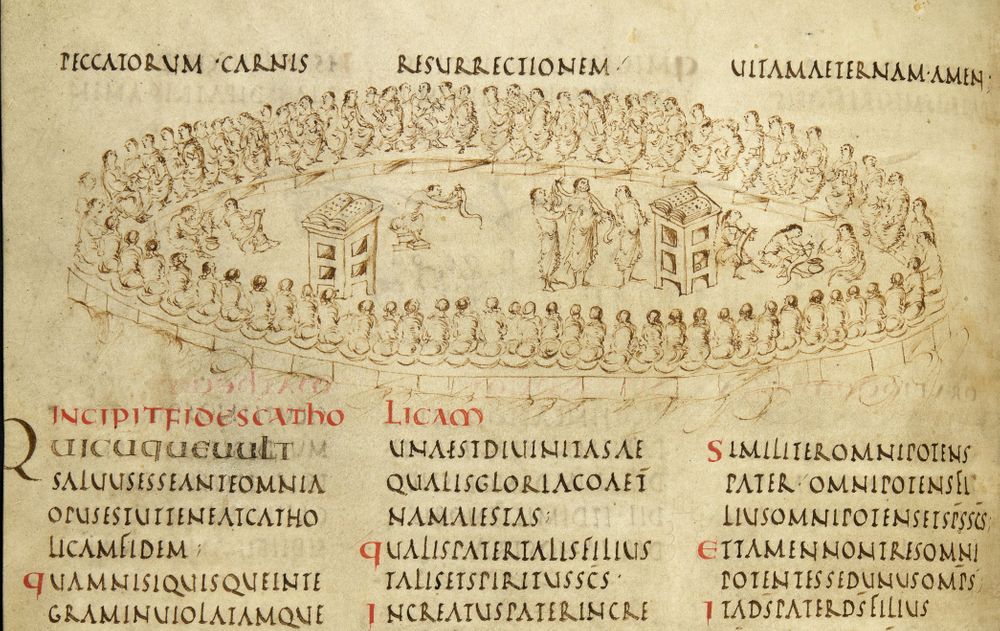

In an attempt to solve the controversy, King Charlemagne (r. 768- 814, emperor from 800) convoked a council to examine the teachings of the Hispanic bishops. At the council of Regensburg in 792, Felix was questioned by one of his most vociferous critics, Bishop Paulinus of Aquileia (d. 802). The assembly at Regensburg rejected and condemned Felix’s doctrine, and so did the council that was held two years later in Frankfurt. This illustration from the Utrecht Psalter (Utrecht, UL, Ms 32) dated to c. 820 is believed to represent the council of Frankfurt of 794. It has been suggested that the man in the middle, flanked by two other figures, is Felix of Urgell or his colleague Elipand of Toledo.3

http://psalter.library.uu.nl/

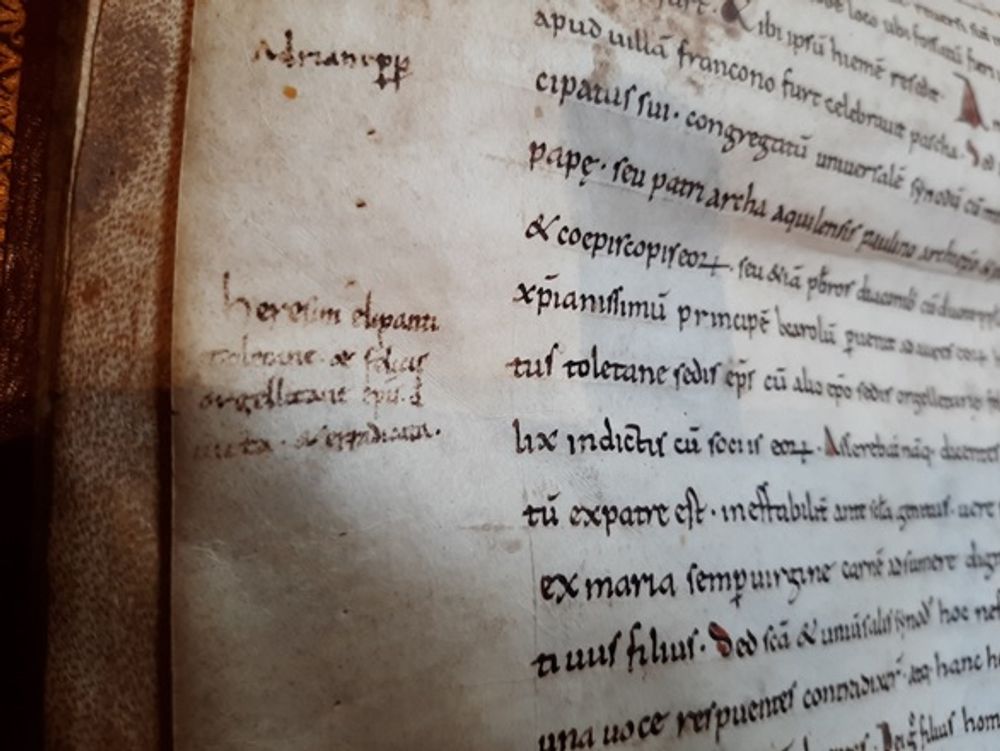

The council of Frankfurt that condemned Hispanic teaching is commemorated in the tenth-century Chronicle of Moissac, written in the Catalonian monastery of Rippol, some 150 kilometres to the north-east of Urgell, Felix’s territory. The chronicle is preserved in ms. Paris, BnF, lat. 4886, dated to the eleventh century. On folio 48v, next to the entry to the year 794, a note in the margin says: “heresim elipanti toletane et felicis urgelletane episcopis (con?)uicta et erradicata”; “The heresy of bishops Elipand of Toledo and Felix of Urgell conquered(?) and eradicated”

https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b10540997j

Yet the doctrine of Elipand and Felix was hardly eradicated at these councils. Once back in Urgell, Felix continued to teach his old doctrine. In 799, Charlemagne summoned Felix to his palace in Aachen, to engage in a public disputation with the court scholar Alcuin of York (d. 804), to settle the matter once and for all. This is a reconstruction of the palace at Aachen, where the debate was held, as archaeologists think it must have looked in the ninth century.

https://www.mozaweb.com/Extra-3D_scenes-Palace_of_Charlemagne_Aachen_9th_century-38645

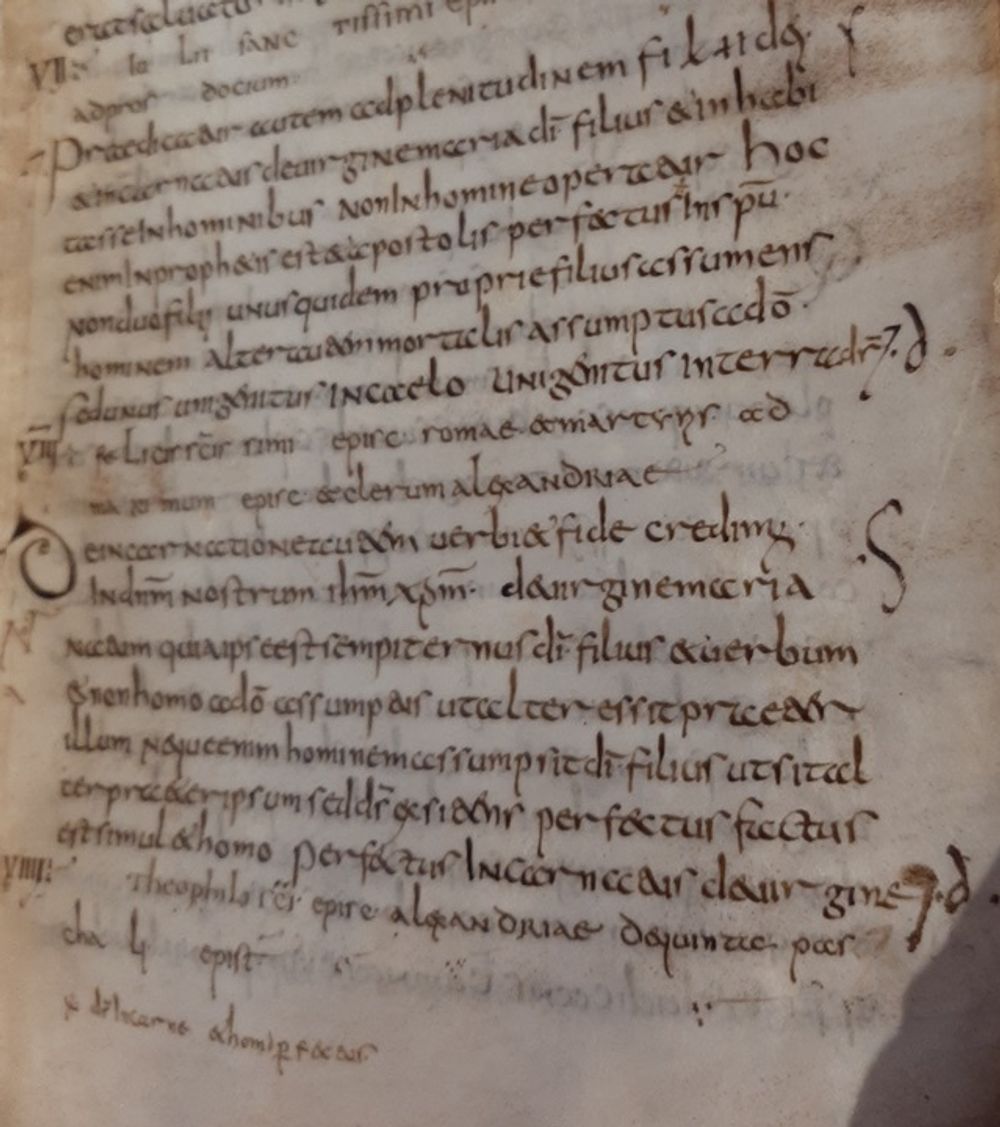

Felix was an experienced debater. A text circulated in the Frankish realm (now lost) of a disputation Felix held with a Saracen. In preparation of the disputation in Aachen, Alcuin consulted the Acts of the Council of Ephesus to find arguments against the teaching of Nestorius so he could use them against Felix. Manuscript Paris, BnF, lat. 1572 that was made in the eighth century and preserved in Tours, contains the Latin translation of the acts of the Council of Ephesus that Alcuin consulted. According to Bernhard Bischoff, Alcuin or his assistant wrote s’s and d’s in the margin to indicate which passages should be copied. The s stands for scribe (copy) and the d for dimitte (stop).4 The s’s and d’s are clearly visible here in the right margin of folio 79r.

https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b9078172j

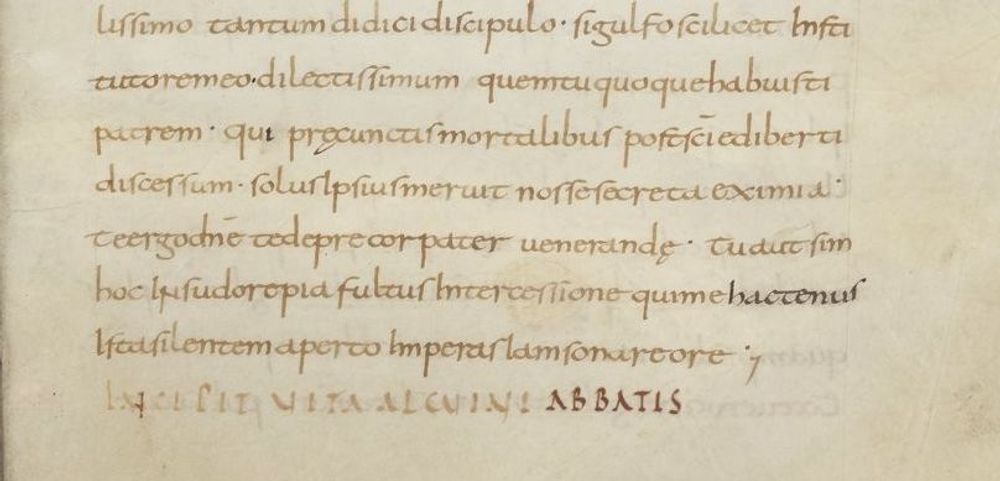

The disputation between Alcuin and Felix in Aachen is described in the Life of Alcuin, written some 20 years after the event. In manuscript Reims, BM, Bibliothèque de Carnegie, 1395, produced in the ninth or tenth century, the Life of Alcuin is part of a collection of martyrdom accounts (passiones). This is an interesting setting, seeing that Alcuin did not suffer a martyr’s death but died of old age. Perhaps his role in fighting the adoptionist heresy made him a martyr in the eyes of the compiler.

https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b8448987p

According to the anonymous author of the Life of Alcuin, the disputation between Felix and Alcuin lasted six days and took place before an audience of bishops, in the presence of King Charlemagne. The author depicted the disputation as an armed clash, in which heavy blows were dealt and arrows flew back and forth. On the sixth day, as the narrative has it, Felix was fatally wounded and fled from the blows of Alcuin’s weapons.5 It was not unusual to use military metaphors to describe the public performance of a disputation, as you can see also here: A controversial art?

https://parker.stanford.edu/parker/catalog/nz663nv2057

Modes of argumentation

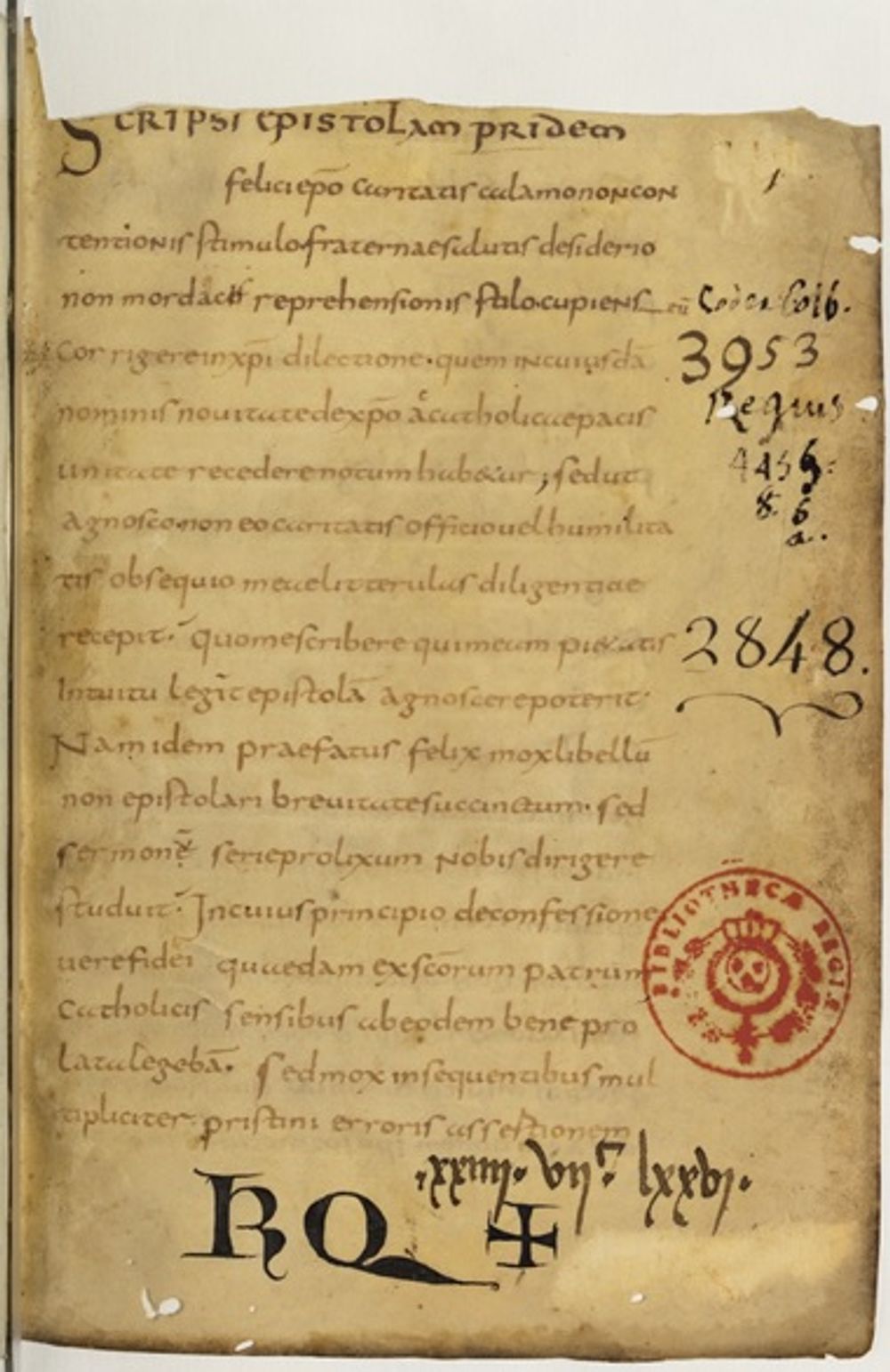

So what were these ‘weapons’ that Alcuin used to out-argue Felix? According to the author of the Life of Alcuin, Alcuin’s weapons were quotations from the Church Fathers. Felix was won over when Alcuin quoted from a letter of Cyril of Alexandria (d. 444), the main opponent of the heretic Nestorius. Alcuin had come across this letter in the dossier of the Council of Ephesus. Manuscript proof was brought to Felix, and when Felix read this quotation from Cyril, the author of the Life wrote, he burst out in tears and recanted his errors.6 Alcuin’s arsenal of dialectical weapons contained, however, more than quotations. Shortly after the debate in Aachen, Alcuin completed his Seven Books Against Felix, based on research he had undertaken in preparation for the disputation. This text offers us a glimpse of the type of argumentation that may have been employed during the disputation. Here we see a ninth-century manuscript from the Tours area (ms. Paris, BnF, lat. 2848) containing Alcuin’s Seven Books against Felix.

https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b90659686

Certain passages in the Seven Books indicate that both participants made use of Aristotelian categorical logic. Yet whereas Alcuin focussed on predicates that are in a subject, Felix appears to have taken the semantic approach, concentrating on predicates that can be said of a subject. To Alcuin’s mind Felix’s logic is inconsistent:

“‘True’ and ‘not true’ can in no way be one; thus ‘true son’ and ‘not true son’ may not both refer to one son; nor can ‘true God’ and ‘God nuncupative’ (i.e. God in name only) be one God [...] There is no way that both predicates can be in one persona.”7

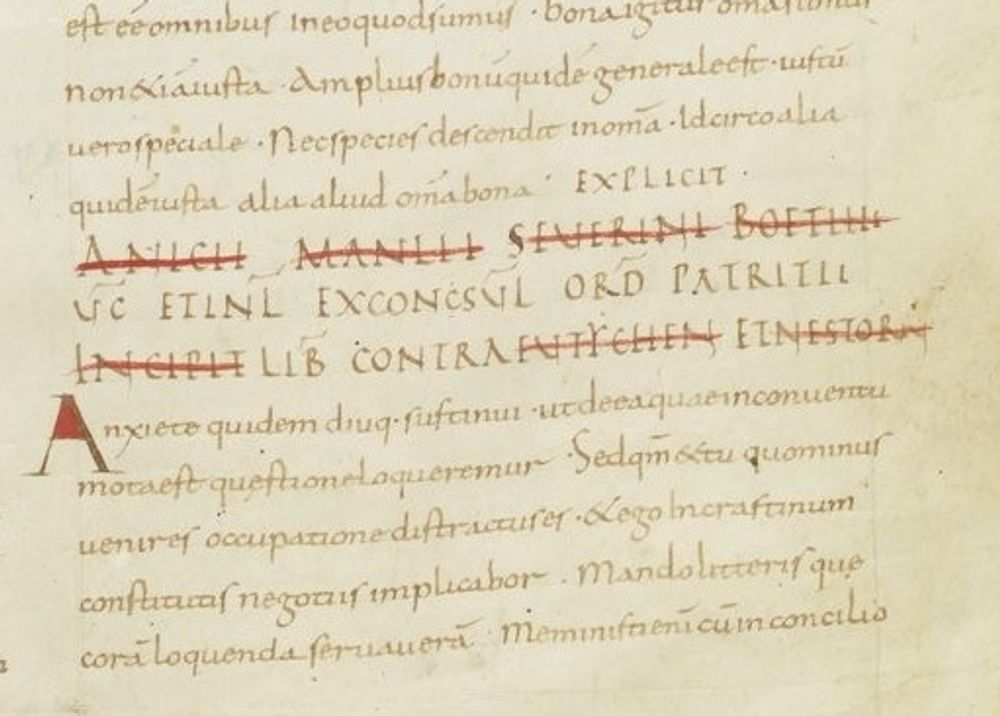

The terms persona and natura were central to Alcuin’s arguments against Felix. They were also key concepts in the debate on the teachings of Nestorius at the council of Ephesus, the council from which Alcuin drew inspiration. Also Boethius (d. 525) discussed persona and natura in his treatise against Nestorius, and his opponent Eutyches.

http://initiale.irht.cnrs.fr/decor/34208

The treatise against Nestorius is one of the five theological treatises of Boethius’ Opuscula sacra. The debate on adoptionism sparked an interest in Boethius’ theological treatises. No less than 14 manuscripts of the opuscula sacra have survived from the ninth century.8 The opscula sacra became important reference texts for scholars who were interested in dialectical argumentation as a means to combat heresy, such as Alcuin’s student Candidus.9

https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b8478988x

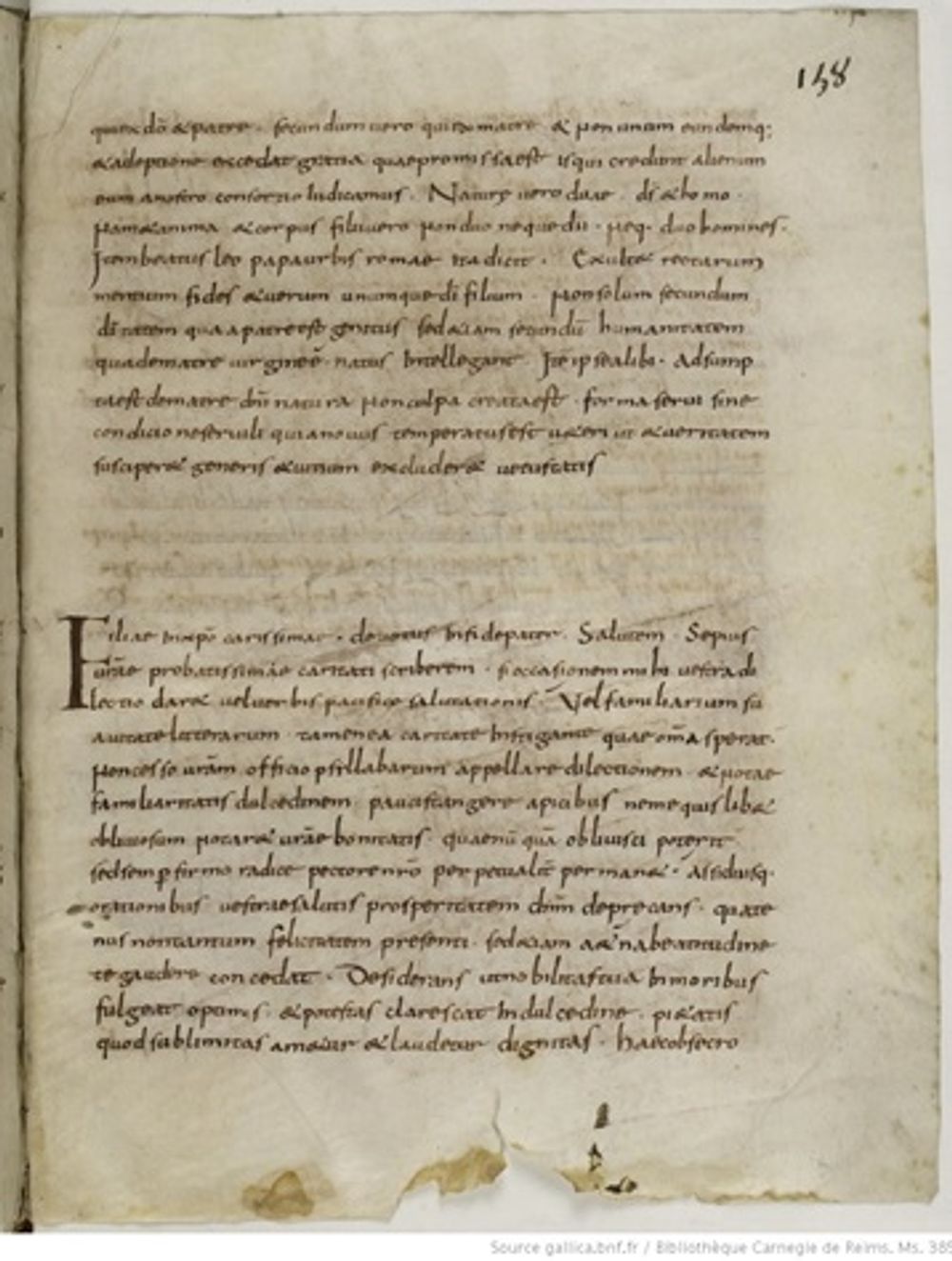

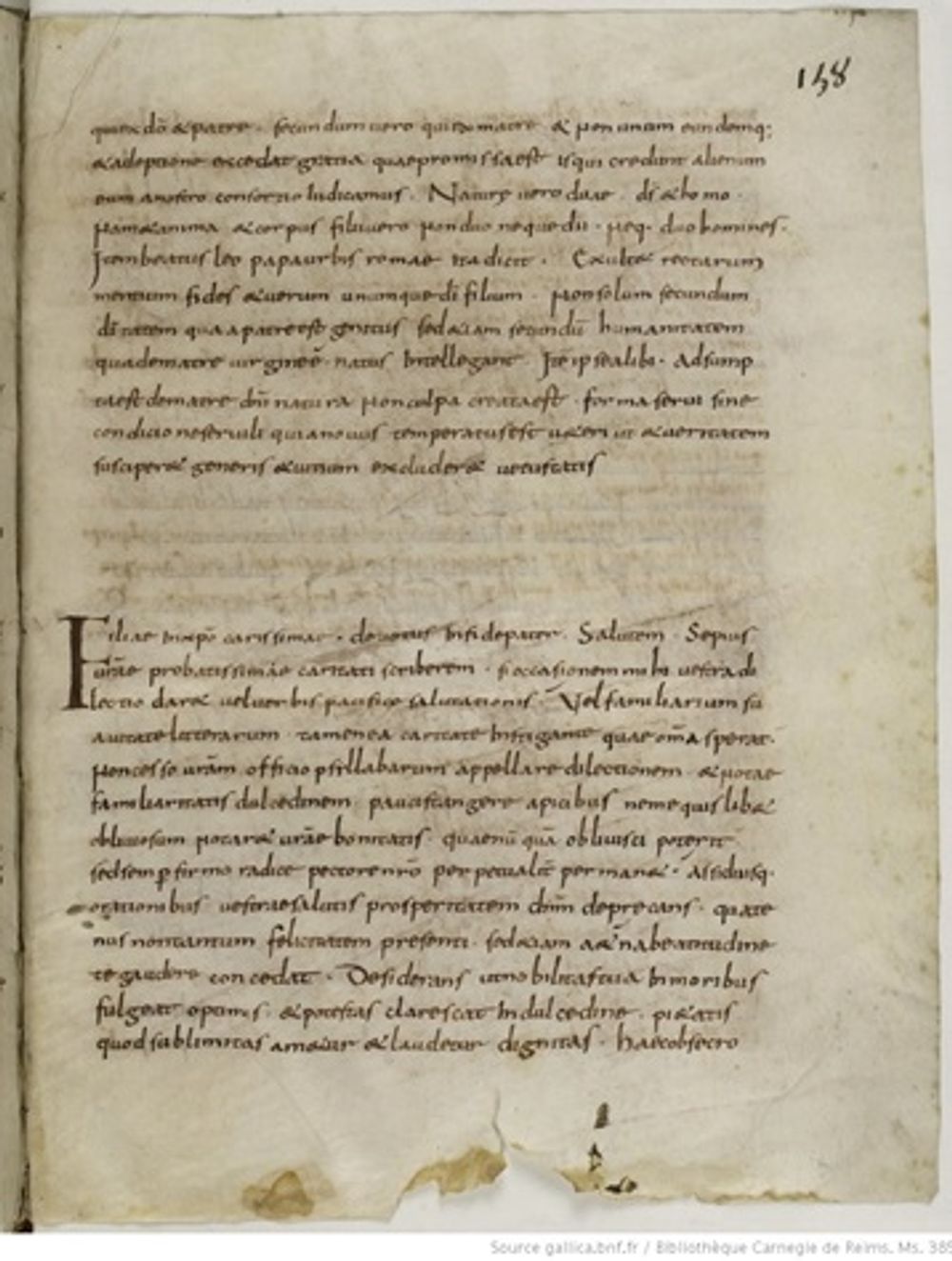

Another glimpse of the argumentation strategies Alcuin may have used during his disputation against Felix in Aachen, is offered in a letter he sent to ‘a noble virgin’ at Charlemagne’s court, who was probably Charlemagne’s relative Gundrada. In this letter, written shortly after debating Felix, he gave Gundrada instructions on how to conduct a disputation with a heretic, and offered to teach her the enquiries of the discipline of dialectic ("interrogationes dialecticae disciplinae") or, loosely translated: the method of dialectical questioning. In manuscript Reims, BM, Bibliothèque Carnegie, 385, Alcuin’s letter to Gundrada follows directly on the profession of faith (confessio) of Alcuin’s opponent Felix (upper half of the page). This manuscript (made in the ninth century in the scriptorium of Reims) formed a dossier on adoptionism that was used as a reference file in another debate, which took place in the Frankish realm some 60 years later.

https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b8448999w

Alcuin presented several examples to Gundrada to illustrate this method of dialectical questioning. This is one such example:

“One should ask whether every man that exists of a body and soul is a proper son of his father. If he says: yes, a proper son, then one should ask whether the soul proceeds from the father just like the flesh. If he says: no, then one should draw the inference: how is a man the proper son of his father if his soul does not proceed from the father, like the flesh?”10

The argumentation scheme that Alcuin presents here is based on the rules of inference. An opponent is led through a series of questions to accept conditional statements, and then ushered to agree upon a conclusion that logically follows from the accepted statements. It is a clear example of a hypothetical syllogism, with an ‘if-clause’ followed by a ‘then-clause’. For the argumentation scheme of a categorical syllogism, which was used more frequently in this period, see here.

http://mdz-nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:bvb:12-bsb00065177-8

It is commonly held that argumentation in the early middle ages mainly rested on arguments found in Scripture and in the writings of the Church Fathers. Although it is certainly true that these texts formed the main body of proof in the debate on adoptionism, Alcuin and Felix did not merely hurl patristic quotations at each other. Participants on both sides of the debate also made use of categorical logic and dialectical methods of enquiry. They acquired their knowledge from intermediate sources, such as the dossier of texts related to the Council of Ephesus or Boethius’ Opuscula sacra, rather than directly from the texts of the logica vetus or the rhetorica vetus. The study of these texts, however, received a boost from the debate on adoptionism, and from the doctrinal debates that followed soon after. For the aftermath of the debate on adoptionism, see the next presentation.

Sources used for this contribution:

Primary sources:

- Alcuin, Contra Felicem Urgellitanum Episcoporum libri septem, PL 101, pp. 119-230.

- Alcuin, Letter to Gundrada (?), Ep. 204, ed. E. Dümmler, Epistolae Karolini Aevi, MGH Epistolae 4 (Berlin, 1895), pp. 337-340

- Vita Alcuini, ed. W. Arndt, MGH Scriptores 15, 1 (Hannover 1887), pp. 182-97.

Secondary literature:

- Bierbrauer, Katharina, ‘Konzilsdarstellungen der Karolingerzeit’, in Rainer Berndt (ed.), Das Frankfurter Konzil von 794. Kristallisationspunkt karolingischer Kultur (Mainz, 1997), pp. 751-765.

- Bischoff, Bernhard, ‘Aus Alkuins Erdentagen’, Medievalia et humanistica 14 (1962) pp. 31-37

- Cavadini, John C., The Last Christology of the West: Adoptionism in Spain and Gaul, 785-820 (Philadelphia, 1993).

- D’Onofrio, Giulio, ‘Dialectic and Theology. Boethius’ Opuscula sacra and their Early Medieval Readers’, Studi medievali 27: 1, pp. 45-47

- Marenbon, John, From the Circle of Alcuin to the School of Auxerre: Logic, Theology and Philosophy in the Early Middle Ages (Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 1981)

- Noble, Thom, ‘Kings, clergy and dogma; the settlement of disputes in the Carolingian world’, in S. Baxter, C.E. Karkov et al. (eds.), Early Medieval Studies in Memory of Patrick Wormald (Farnham, Surrey, 2009), pp. 237-52

- Erismann, Christophe, ‘The medieval fortunes of the Opuscula sacra’, in John Marenbon (ed.), The Cambridge Companion to Boethius, Cambridge Companions to Philosophy (Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2009), pp. 155-178.

- Renswoude, Irene van, ‘The art of disputation: dialogue, dialectic and debate’, in: Early Medieval Europe 25: 1 (2017), pp. 38-53.

- Sieben, Hermann-Josef, Konzilsdarstellungen – Konzilsvorstellungen. 1000 Jahre Konzilsikonographie aus Handschriften und Druckwerken (Würzburg, Echter, 1990).

Contribution by Irene van Renswoude. I thank Janneke Raaijmakers for her critical reading and always excellent suggestions for my contributions, and Renée Schilling for bringing the story of Alcuin and Felix to life.

Cite as, Irene van Renswoude, “Debate on adoptionism”, The art of reasoning in medieval manuscripts (Dec 2020), https://art-of-reasoning.huygens.knaw.nl/adoptionism. ↑Cavadini, 1995, 7. ↑

Sieben, Konzilsdarstellungen, 1990, p. 22; Bierbrauer, ‘Konzilsdarstellungen’, p. 758. ↑

Bischoff, 1962. ↑

Vita Alcuini, c. 10, ed. W. Arndt, MGH Scriptores 15.1, p. 190. ↑

Vita Alcuini, c. 10, ed. W. Arndt, MGH Scriptores 15.1, p. 190. ↑

Alcuin, Adversus Felicem, trans. Cavadini, 1993, 90. ↑

D’Onofrio, 47-48. ↑

Erismann 155, D’Onofrio 48. ↑

Alcuin, Ep. 204, ed. Dümmler p. 338. ↑

Next Read:

Next Read: