Alcuin and dialogue

The use of dialogue as a teaching tool1

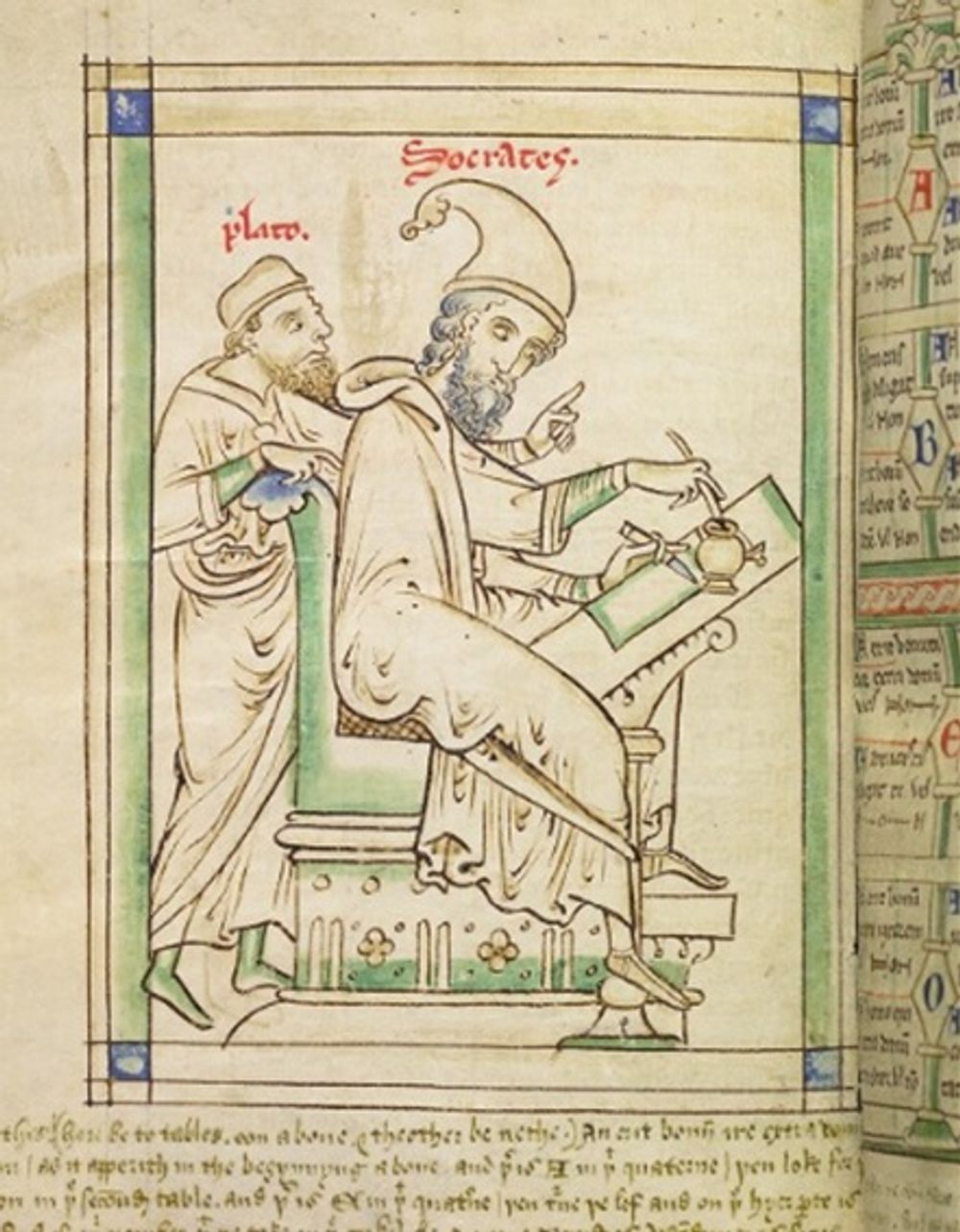

Dialogue was a powerful tool in teaching, as Plato already showed in the dialogues of Socrates and his students: a student could ask his teacher questions, and thus learn from the master’s knowledge, or the teacher could ask his student questions, and thus check whether he had learned properly about the subjects at hand. A famous adopter of the dialogue as a teaching form is Alcuin of York (735−804), the well-known monk/abbot/bishop/teacher and scholar at the court of Charlemagne (742-814).

https://digital.bodleian.ox.ac.uk/objects/5885f370-ffea-4c09-9d01-a0d4399e82af

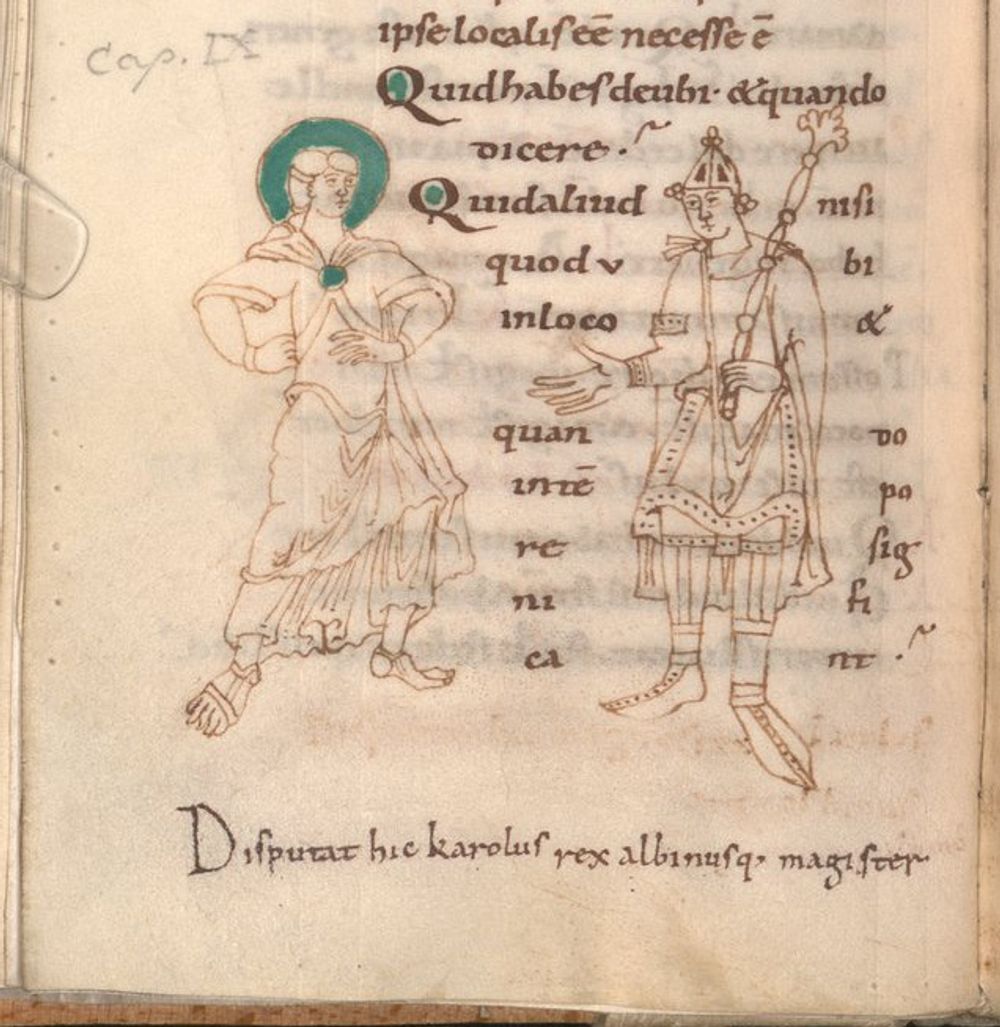

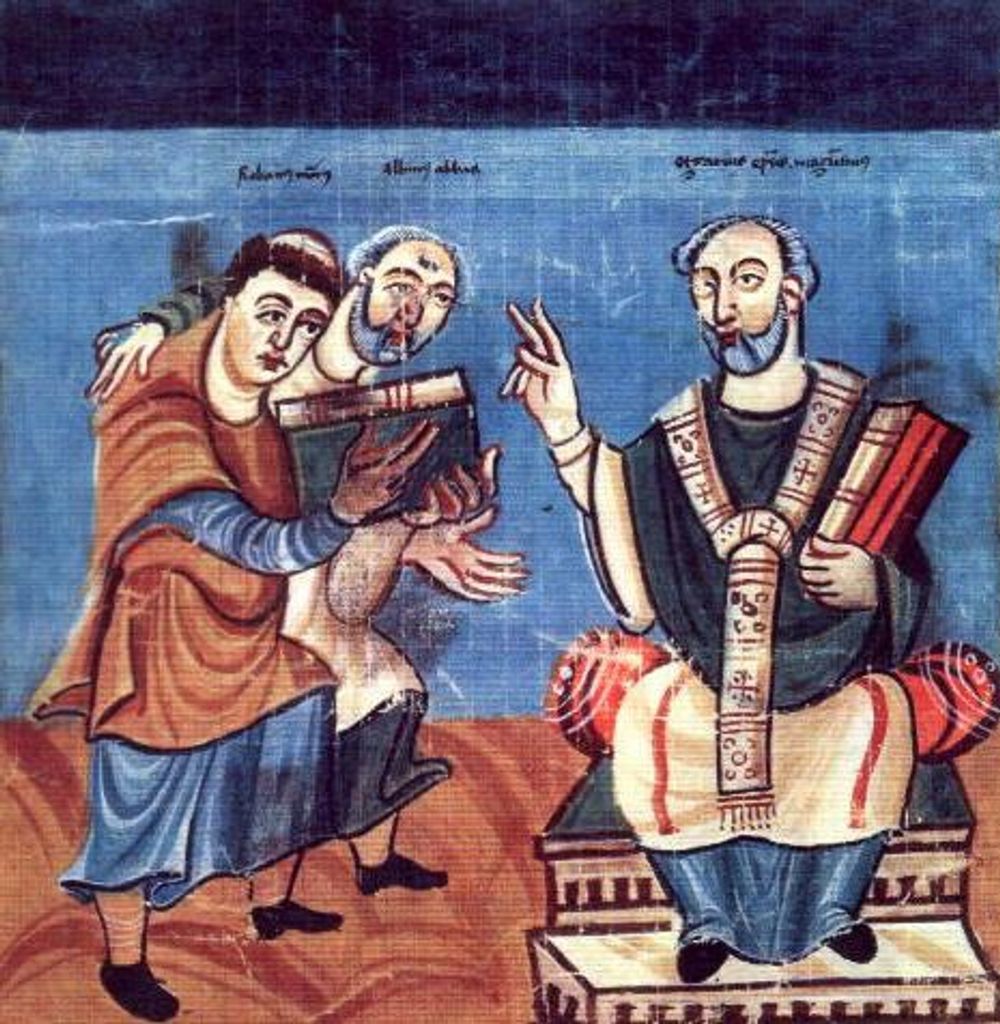

Alcuin of York very much identified as a teacher in his works. Among his didactic works are treatises on grammar, dialectic, dialogues (disputationes), a work on astronomy and a set of mathematical riddles for students. In his teaching, he showed a preference for the dialogue as the ideal form for his didactic texts: his introduction to the art of dialectic is in the form of a dialogue between himself and Charlemagne, with Charlemagne asking questions and Alcuin answering. Here is a copy of Alcuin’s Dialogus de dialectica in manuscript Munich, Bayerische Staatsbibliothek, Clm. 19437, which was made in the tenth, or early eleventh century in Tegernsee. On fol. 19v we see a portrait of Alcuin (on the left) and Charlemagne (on the right) disputing: “Disputat hic karolus rex albinusque magister”, “Here King Charles and master Albinus dispute”. Albinus, “the white one”, was one of Alcuin’s nicknames. Note that Alcuin has been given the halo of a saint.

http://mdz-nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:bvb:12-bsb00065177-8

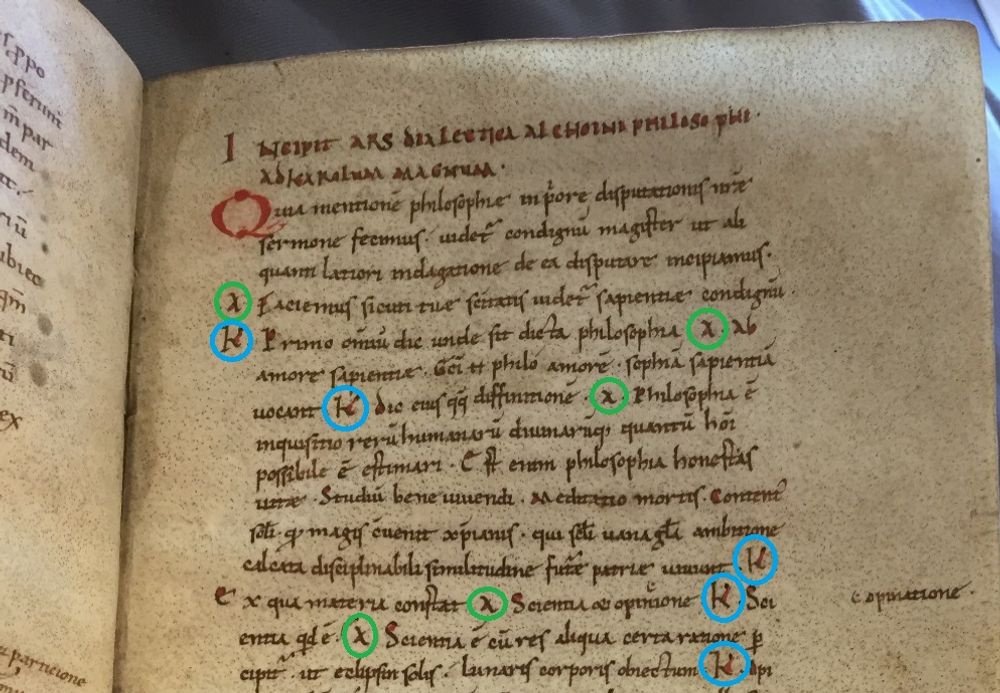

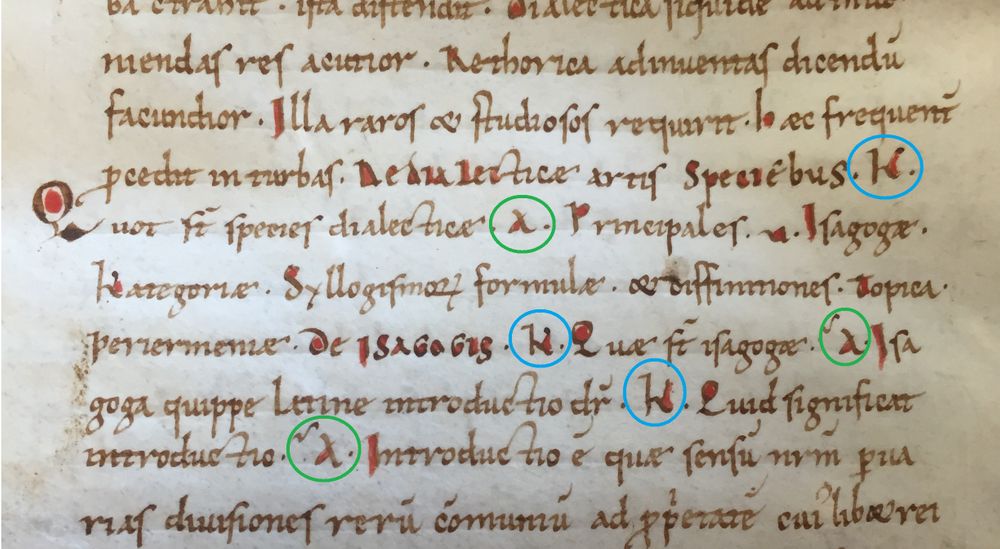

In manuscript Leiden, UB, BPL 84 several texts are found, and among them is Alcuin’s Dialogue on Dialectica. On this page, fol. 90r, the text opens: “INCIPIT ARS DIALECTICA ALCHOINI PHILOSOPHI. AD KAROLUM MAGNUM”; “The art of reasoning of Alcuin the Philosopher for Charlemagne begins.” Questions from Charlemagne are marked with K (Karolus), answers from Alcuin with A (Alcuin).

http://hdl.handle.net/1887.1/item:2348775

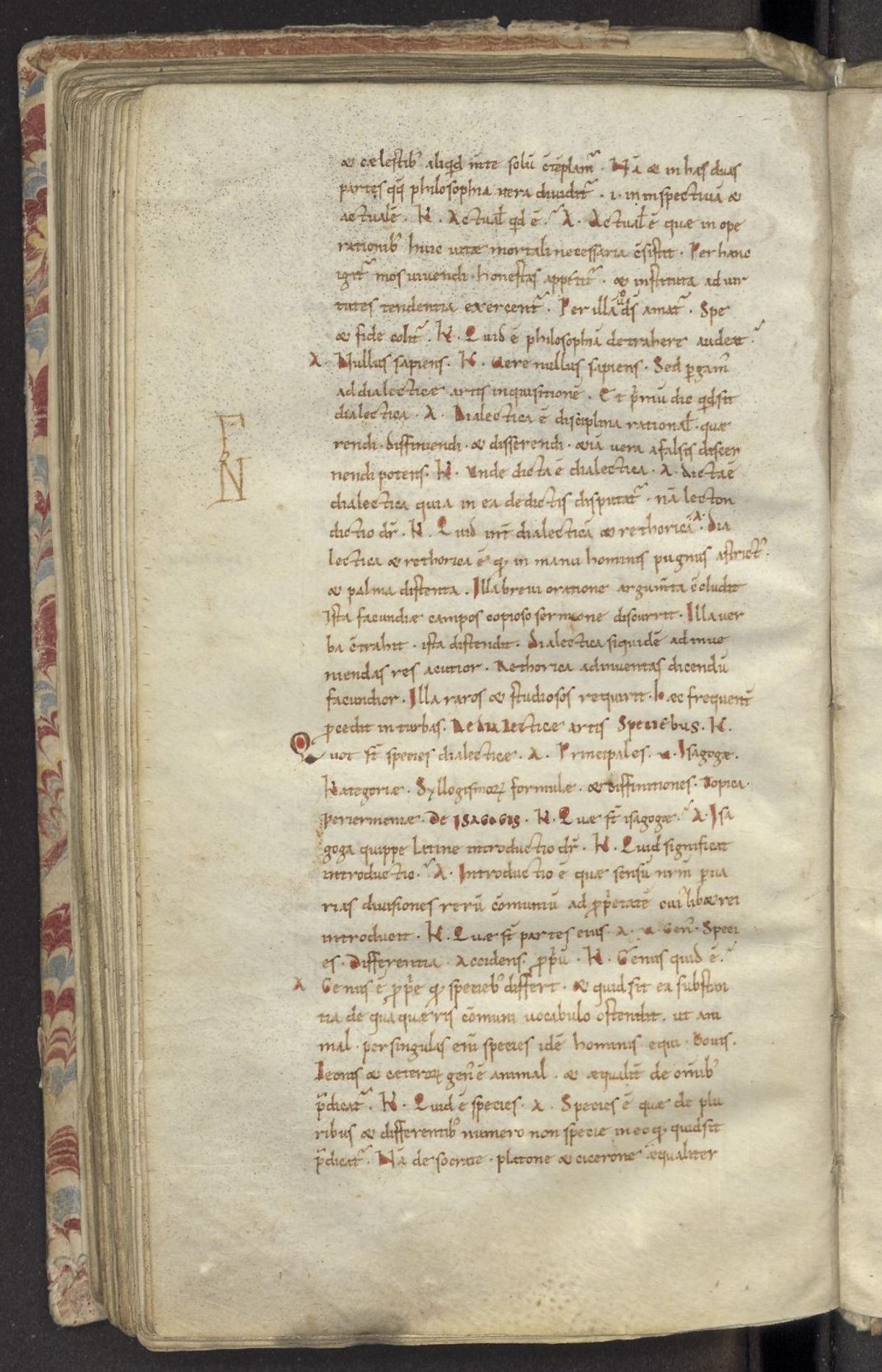

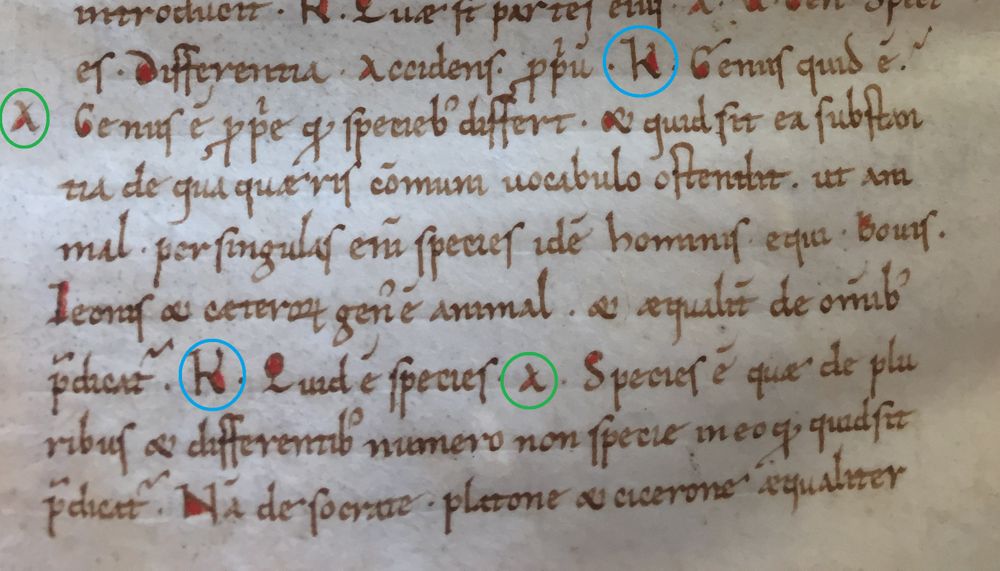

Here, on f. 90v, you can see how Alcuin patiently explains the art of dialectic, its terminology, its components and what you can do with it. In the terminology, one immediately recognizes the basic curricular texts on dialectic: Porphyry’s Isagoge, Pseudo-Augustine’s Categoriae Decem, Boethius’ treatises on syllogisms, Cicero’s Topica, et cetera. He illustrates with examples to make the dry text more lively.

Charles: How many species are there in dialectic?

Alcuin: The most important are 5: ‘isagogae’, categories, syllogistic formulas and definitions, ‘topica’, and ‘perermeniae’.

Charles: What are ‘isagogae’?

Alcuin: Isagoge is the (Greek) word for Latin ‘introductio’, ‘introduction’.

Charles: What does ‘introduction’ mean?

Alcuin: Introduction is …

http://hdl.handle.net/1887.1/item:2348775

Charles: What is ‘genus’?

Alcuin: ‘Genus’ is what can be divided into species: it describes whatever you are investigating in an inclusive word, such as ‘animal’. For each individual species – man, horse, ox, lion etc. – ‘animal’ is the genus and is applied to them all.

Charles: What is ‘species’?

Alcuin: ‘Species’ is …2

http://hdl.handle.net/1887.1/item:2348775

Chains of teachers and students

The relation between teachers and students was important in the Middle Ages: teachers kept in touch with their students and the other way around, and used these relations to define their identity. Alcuin sent letters to his students, gave them affectionate nicknames and admonished them to be good scholars, Christians and friends. Thus these teachers and students formed intellectual networks, which created a sense of shared intellectual identity in the Carolingian empire.

A famous network of teachers and students consists of:

Alcuin, who taught Hrabanus Maurus,

who taught Lupus of Ferrières,

who taught Heiric of Auxerre,

who taught Remigius of Auxerre.

Heiric of Auxerre was also taught by Haymo of Auxerre, who was taught by Murethach. Remigius of Auxerre was the teacher of Odo of Cluny and others. Teachers and students formed tight-knit networks of relationships and knowledge exchange.

We can see such an affectionate relationship depicted here, in manuscript Vienna, ÖnB, cod. 652, on fol. 24: Hrabanus (left) and Alcuin (middle) dedicate a work to Archbishop Otgar of Mainz (right). As the teacher (with more seniority), Alcuin has his arm around Hrabanus’ shoulder, expressing his support when introducing him to the Archbishop.

http://data.onb.ac.at/rep/10048D05

Sources used for this contribution:

- E.A. Matter, “Alcuin’s Question-and-Answer Texts”, Rivista di Storia della Filosofia 45.4 (1990), 645-656

- M. Garrison, “The Social World of Alcuin: Nicknames at York and at the Carolingian Court”, in Alcuin of York: Scholar at the Carolingian Court, eds. Luuk Houwen and A.A. MacDonald, Germania Latina 3/Mediaevalia Groningana 22, Groningen 1998, 59-79

- M. Gibson, “Boethius in the Carolingian Schools”, Transactions of the Royal Historical Society 32 (1982), 43-56 (Artes and Bible in the Medieval West, Variorum, 1993, VI.)

-

Contribution by Mariken Teeuwen.

Cite as, Mariken Teeuwen, “Alcuin and dialogue”, The art of reasoning in medieval manuscripts (Dec 2020), https://art-of-reasoning.huygens.knaw.nl/alcuin. ↑ -

Transl. Gibson, ‘Boethius in the Carolingian Schools’, 46. ↑

Next Read:

Next Read: