Women and disputation

Did women even have a role to play?1

This section explores the role of women in the culture of disputation from late Antiquity to the high Middle Ages. Medieval practices of disputation were intricately connected to education and teaching. Few women in the Middle Ages had the opportunity to study the liberal arts or were allowed to teach and speak in public. The prescription found in Scripture that women were to remain quiet restricted their access to debate and disputation. In his letter to Timothy, the Apostle Paul was believed to have written: “I do not permit a woman to teach or to exercise authority over a man” (1 Tim 2,12). This hardly left any room for women to persuade or dispute. Yet occasionally we do hear of a woman who spoke in public or engaged in disputation with men. Here follow five portraits of disputing women from Antiquity to the high Middle Ages. Many of these portraits were drawn by others, but on some rare occasions we hear a woman speaking with her own voice. The portraits are listed chronologically, by the period in which they were written.

http://initiale.irht.cnrs.fr/decor/104988

Portrait I: Marcella of Rome (325-410)

Marcella was a wealthy aristocrat from a Christian family. She founded a community of women, who practiced an ascetic lifestyle and were dedicated to biblical studies. According to church father Jerome (d. c. 420), who wrote a biography of Marcella shortly after her death, her knowledge of Scripture was widely known. People turned to Marcella to discuss interpretations of Scripture with her.2

Jerome pictured Marcella as a modest woman, who was careful not to present her opinions as her own:

“Whenever she was asked a question she would give her opinion not as being her own but as being mine or someone else’s so as to admit that she was a student in that in which she was a teacher. For she knew that the apostle had said: I do not allow a woman to teach.”3

Although Jerome portrayed Marcella as a humble female scholar who knew her place among men, he also acknowledged that Marcella’s opinions actually were her own. She was a teacher, but presented herself as a student – a clever way to circumvent Paul’s prohibition that barred women from teaching men.

http://initiale.irht.cnrs.fr/en/decor/13176

Jerome said Marcella inspired him to write a commentary on Paul’s epistle to the Galatians. He framed the commentary as a book of consolatory exegesis, written in her honour. This opening miniature of Jerome’s Commentary on the Book of Daniel in manuscript Dijon, BM, 132 (Citeaux, Abbey of Notre-Dame, twelfth century) shows Jerome offering his work to Marcella, who is accompanied by her student Principia. The miniature attests to Marcella’s reputation as Jerome’s patron and muse.

http://initiale.irht.cnrs.fr/en/decor/13176

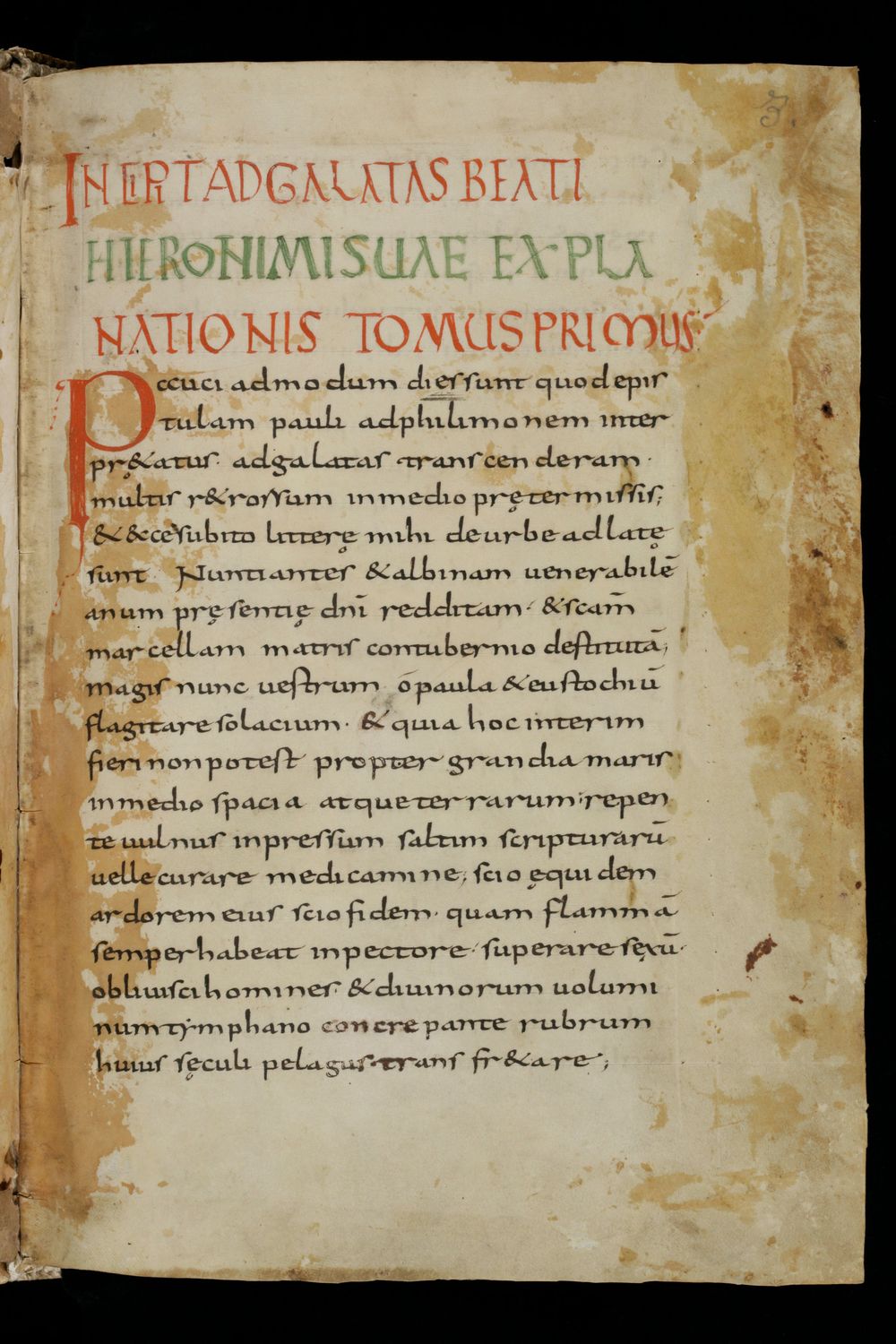

In the prologue to his Commentary on the Epistle to the Galatians (c. 389), Jerome praised Marcella’s zeal for study and her ardour, which motivated her “to transcend her sex”. Her stimulating questions contributed to the genesis of his own work, he said, all the more since she was not easily satisfied with his answers. Jerome wrote: “She did not accept as true whatever answer I would give her; and my authority did not prevail with her if it was not supported by reason. She examined everything and weighed it all in her sagacious mind, such that I felt that she was not so much my student as my judge.”4 The image on the right shows the rubric opening Jerome’s Commentary on the Epistle to the Galatians in manuscript St. Gallen, Stiftsbibliothek, 128, dated to the first third of the ninth century.

https://www.e-codices.unifr.ch/en/searchresult/list/one/csg/0128

When Marcella died in 410, Jerome wrote an obituary, in which he recalled how Marcella publicly opposed those who supported the doctrines of the scholar Origen (d. 254), who had taught that God was incorporeal. At first Marcella refrained from participating in the debate, Jerome wrote, but when it seemed that Origen’s doctrines gained ground in Rome, Marcella stood up: “It was then that the holy Marcella, who had long held back lest she should be thought to act from party motives, threw herself into the breach. Conscious that the faith of Rome was now in danger, and that this new heresy was drawing to itself not only priests and monks, but also many of the laity […] she publicly withstood its teachers choosing to please God rather than men.”5

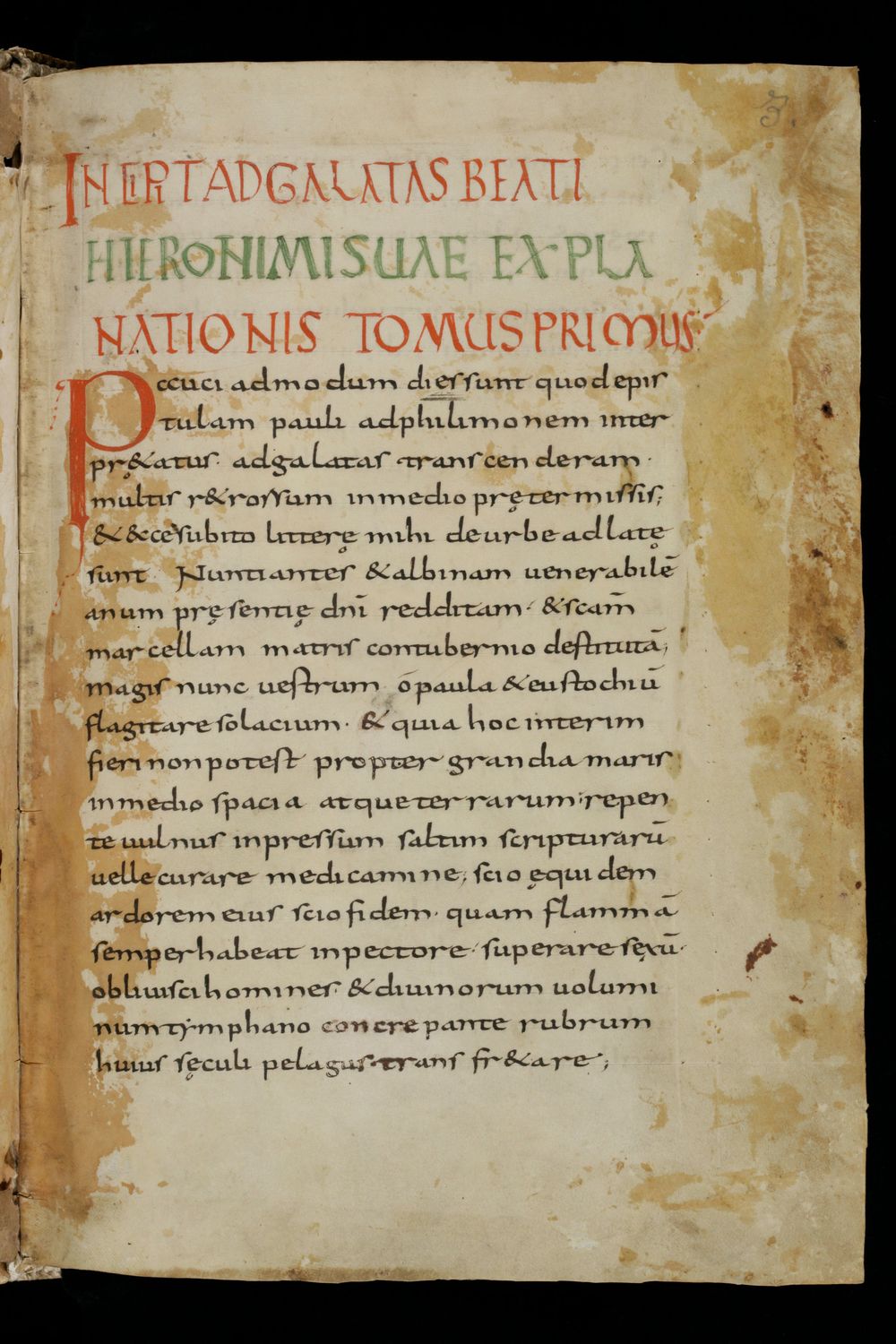

According to Jerome, Marcella played such a vital role in the debate that the success of the condemnation of the heretics should be largely attributed to her efforts.6 On the right you can see a portrait of Origen, ca.1160. Above the portrait is written: “scribere cum penna doceat me sacrata maria” – “May holy Mary teach me to write with a pen.”

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Category:Origen#/media/File:Origen3.jpg

Portrait II: Eulalia of Mérida (d. 305)

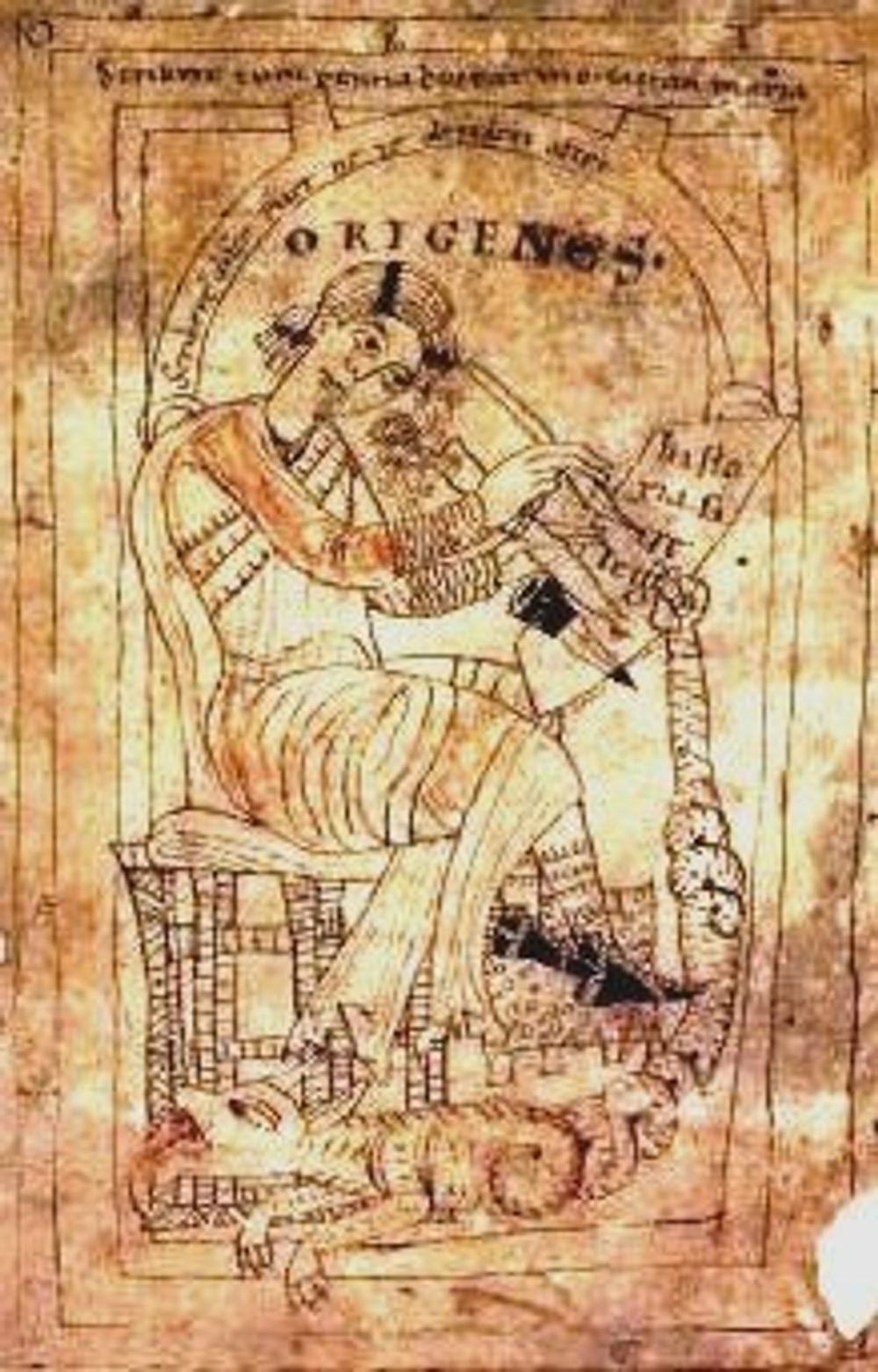

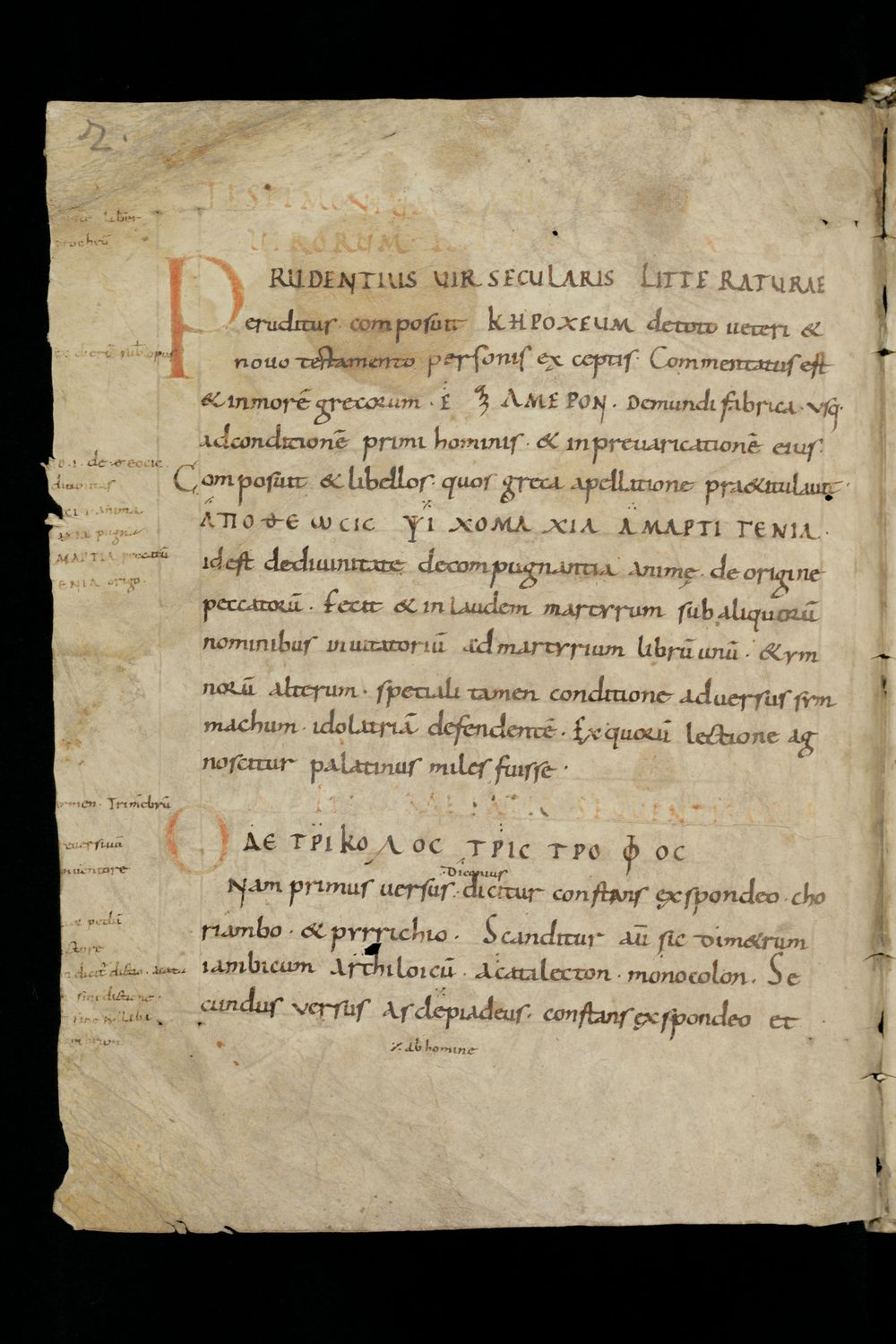

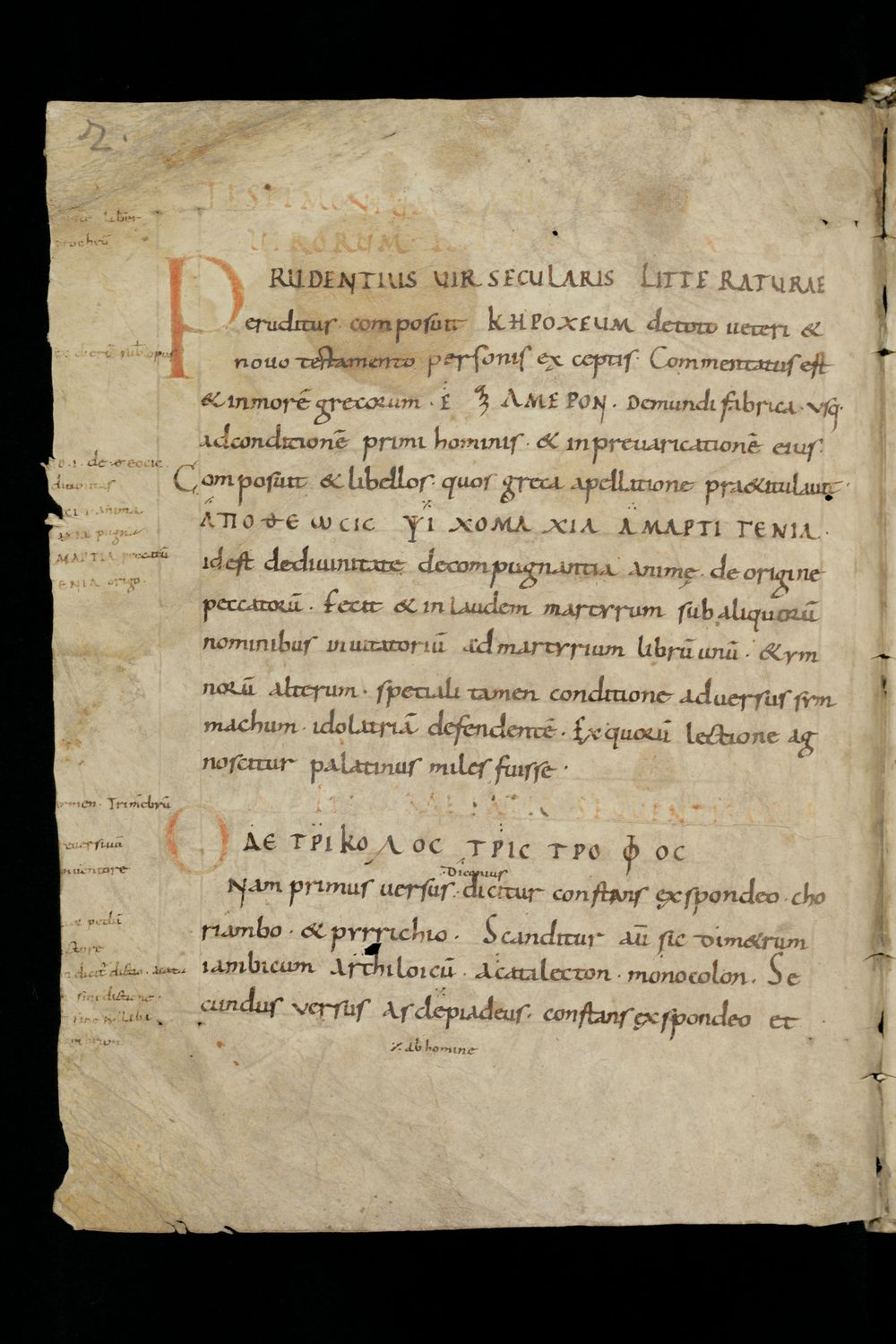

Eulalia of Mérida is believed to have suffered martyrdom in 305 during the Diocletian persecution. The first author to write about Eulalia was the poet Prudentius (fl. 400), born in the Roman province of Tarragon (Northern Spain). In his Peristephanon, ‘Crowns of martyrdom’, he praised Eulalia’s bold resistance to Roman magistrates. This image shows the verso side of the first folio of the first codicological unit of ms. St. Gallen, Stiftsbibliothek, 134, containing Prudentius’ Peristephanon and Cathemerinon. This unit, dating to c. 900, was later bound together with a Latin commentary on Aristotle’s On Interpretation (Periermeneias) (in a copy dating to the thirteenth century) and with Boethius’ Opuscula sacra (in a copy dating to c. 1000).

https://www.e-codices.unifr.ch/en/list/one/csg/0134

In his Crowns of Martyrdom Prudentius recounted how thirteen-year old Eulalia ran away from her parents, who had brought her to the countryside to escape the persecution of Christians. She went straight to the law court of the governor Dacian at Emerita to profess her faith in Christ. During her trial, she defied the Roman magistrates, who were in charge of questioning her, with provocative counter-questions. When the magistrates tried to persuade her to change her position, Prudentius wrote, Eulalia spat in the eyes of her interrogator, abused the governor and destroyed the symbols of his religion.7

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:MEpiscopalVIc-Martorell-Eul%C3%A0lia-neu.jpg

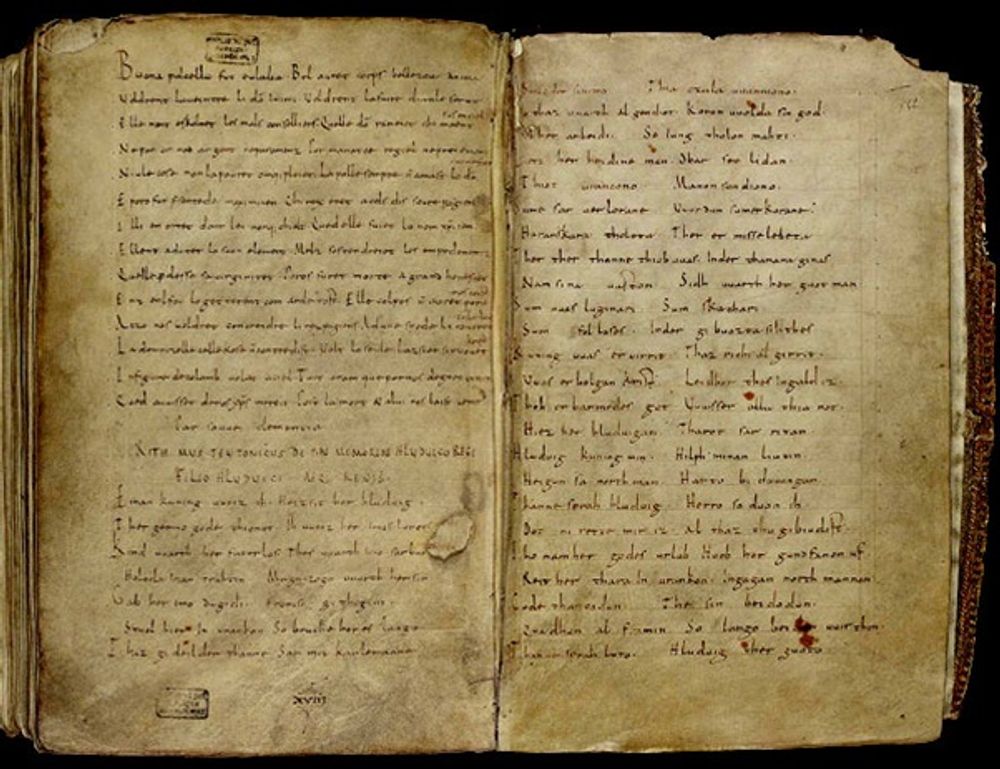

In Prudentius’ portrayal, Eulalia does not participate in a rational, dialectical disputation, but she surely ‘talks back’ when questioned. As is the case with many martyrdom narratives, the historical veracity of Eulalia’s trial, as described by Prudentius, is in doubt. Yet it is significant that Prudentius could imagine a woman arguing with Roman officials. A remarkable feature of late antique martyr narratives is that female martyrs are often depicted as speaking freely in public.8 In the sixth century, Eulalia’s popularity spread from Spain to Gaul. The poet Venantius Fortunatus (d. 610), who resided in Poitiers, wrote a poem about her. Also, the oldest extant French vernacular poem, dating to the late ninth century, is dedicated to Eulalia . This image shows two pages from the Cantilène de Sainte Eulalie (Song of St. Eulalia) in manuscript Valenciennes, Bibliothèque Municipale, 150, made in the abbey of Saint-Amand around 881. The verses are written in the langue d’oil, a vernacular language spoken in northern France and southern Belgium.

https://data.biblissima.fr/entity/Q198631

Portrait III: Gundrada, (fl.800)

Gundrada was a lady at the court of Charlemagne. She was Charlemagne’s cousin and the sister of the counsellors Adalhard and Wala, abbots of Corbie. It has been suggested that Gundrada taught at the court.9 According to Radbert of Corbie (d. 865), who was a close friend of Gundrada’s brothers, Gundrada was “a virgin more close to the king and most noble of noble ones”.10 Janet Nelson has proposed it may have been Gundrada’s decision to remain a virgin that enabled her, in her advisory and educational role, to act as conduit between persons at court and the ruler.11 The court scholar Alcuin of York often addressed Gundrada with her nickname or pseudonym: Eulalia, ‘of noble speech’. In the literary circle of Charlemagne’s entourage pseudonyms were chosen (or given) from a resemblance with a person from Antiquity.12 Presumably Gundrada reminded Alcuin of Eulalia, the outspoken martyr of Mérida.

https://www.wikiwand.com/nl/Spiegel_Historiael_(handschrift)

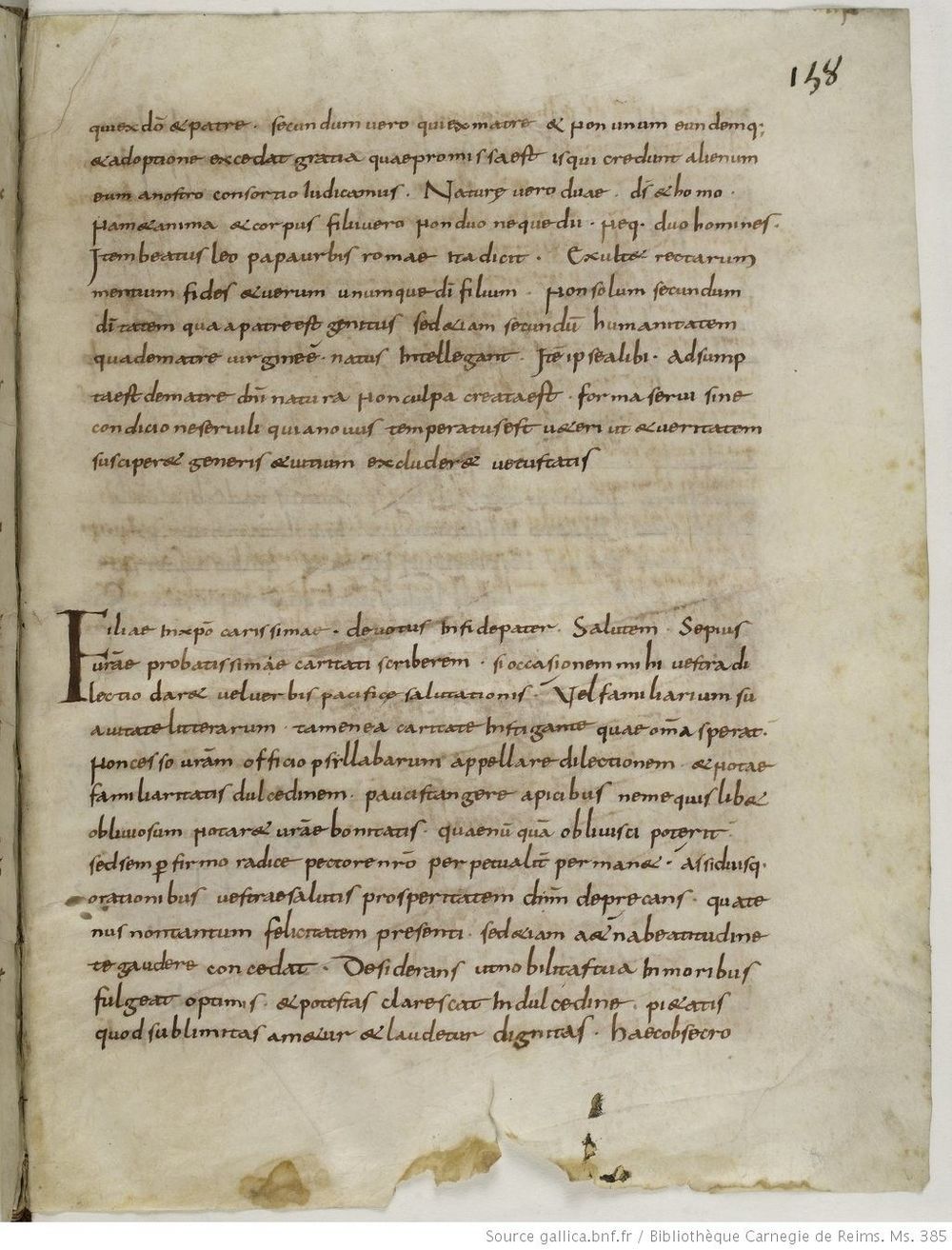

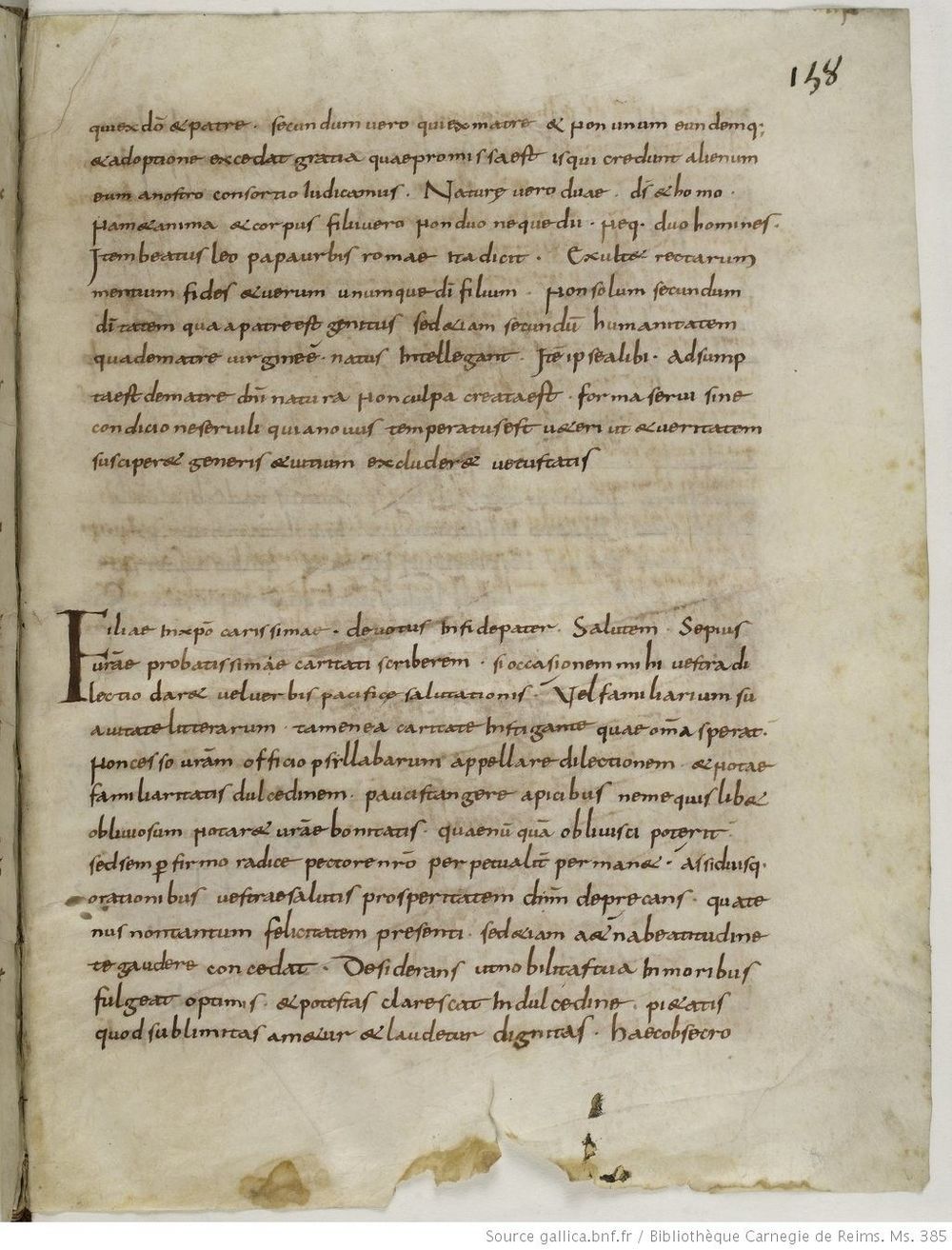

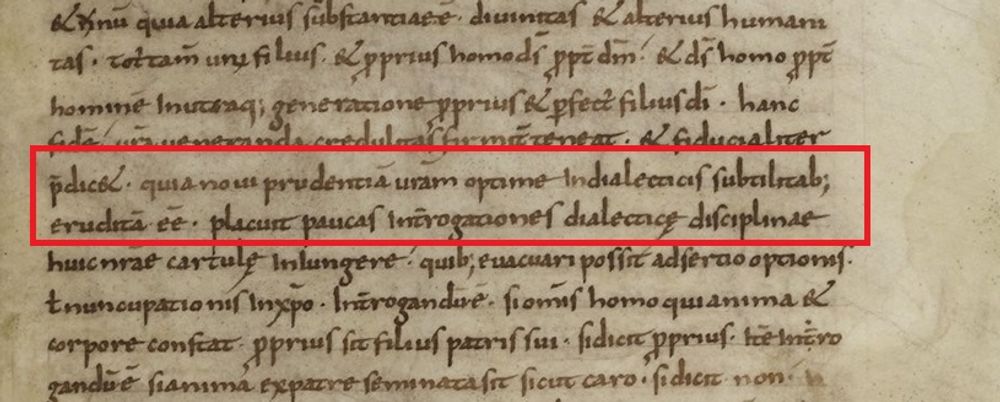

In 799 or 800, Alcuin sent a letter to ‘a noble virgin’ at the court, probably Gundrada, with instructions on how to conduct a disputation with a heretic. In his letter, Alcuin praised Gundrada for her knowledge of dialectic and offered to teach her the method of dialectical enquiry. On this letter and Alcuin’s proposed method, see, furthermore, Debate on adoptionism. Alcuin’s letter to Gundrada directly follows the confessio of Felix (upper half of the page), the bishop whom Alcuin had just defeated in a disputation on adoptionism at the palace in Aachen.

https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b8448999w

In his letter, Alcuin explained that he considers this method to be helpful in refuting heretics, in particular those who teach the doctrine of adoptionism. Apparently, Alcuin had no trouble envisioning his addressee debating issues of doctrine with a heretic, and neither does he consider it inappropriate for a lady at court to engage in a disputation. Alcuin offers Gundrada words of praise: “I have known you to be well versed in the subtleties of dialectic.”

https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b8448999w

Portrait IV: Katherine of Alexandria (d.305)

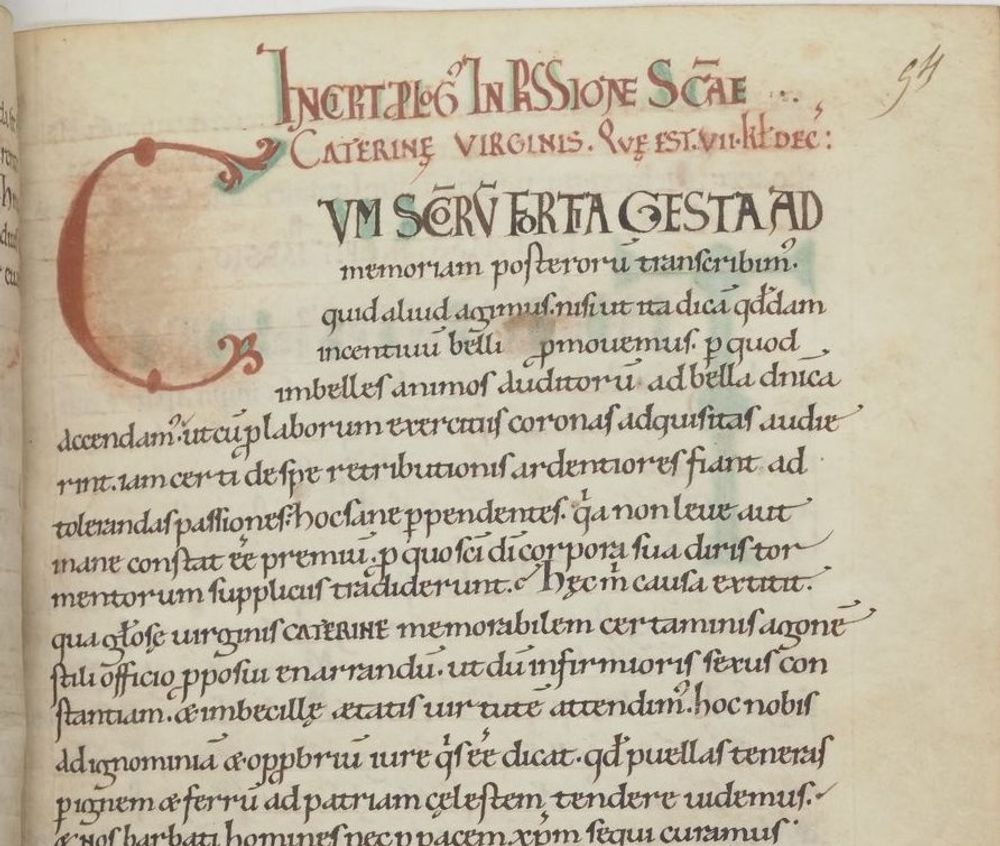

Like Eulalia, Katherine of Alexandria is reputed to have suffered martyrdom in 305. The cult of St. Katherine emerged during the eighth century in the Byzantine East. The earliest extant manuscripts of the Latin passio of her life and death date to the eleventh century. She is also known as ‘Katherine of the Wheel’, after the instrument with which she was tortured

It has been suggested that her legend was modelled on the life and death of the Greek philosopher Hypatia.13 According to the eleventh-century narrative, Katherine was fourteen years old when she went to the court of Emperor Maximian (r. 286-308) to rebuke him for his persecution of Christians. Maximian summoned 50 orators and philosophers to dispute her and to refute her Christian arguments, but Katherine won the debate.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Catherine.Wheel.jpg

Manuscript Paris, BnF, Lat. 1970, written in Fécamp in the eleventh century, is one of the earliest extant manuscripts containing the passio (martyrdom) of Katherine. Katherine’s passio was composed in the eleventh century by an anonymous author who was active in northern France and the Low Countries. The author presents Katherine as a very learned woman, despite her young age. When she became a Christian, Katherine rejected “the philosophical discussions of Homer and the strangling syllogisms of Aristotle”.14 Her dismissal of classical expertise and strategies did not keep her from beating the learned philosophers and orators in debate. Her biographer made use of a familiar literary trope that contrasted simple (but wise) Christian eloquence to sophistic argumentation. For another example of a woman participating in a disputation in a (fictional) dialogue, see Leiden, UB, GRO 22.

https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b10539943g

This mural painting illustrates the disputation and arrest of Katherine. It is part of a set of murals in Catalan Romanesque style that were painted on the walls of the cathedral of La Seu d’Urgell between 1242-1255. We see Katherine holding a book and arguing with a group of philosophers, who are seated on the floor. She is accompanied by a group of preachers. The murals were created after a period of persecution of Cathars in Catalonia. The iconography of the scene underlines the importance of employing dialectic against heretics.15 The murals were removed from the cathedral of La Seu d’Urgell between 1927 and 1933 and are now in the Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya.

https://www.museunacional.cat/en/colleccio/dispute-and-arrest-saint-catherine-cathedral-la-seu-durgell/anonim-catalunya/214241-000

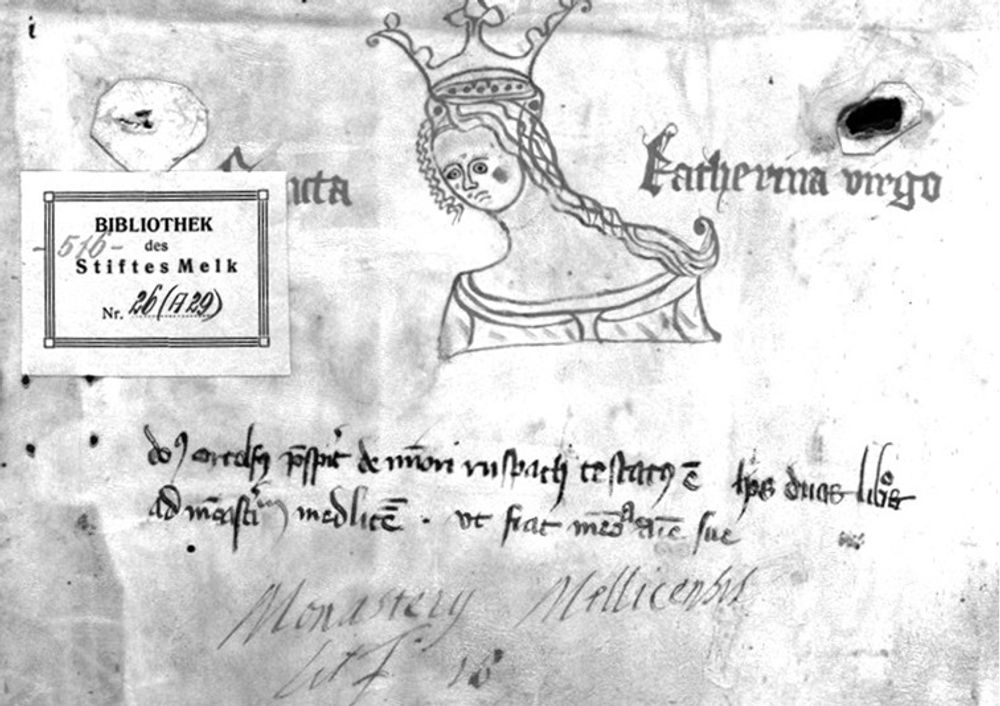

Saint Katherine’s popularity was undiminished in the later middle ages This pastedown on the inside front-cover of manuscript Melk, Stiftsbibliothek, 516 (early fourteenth century) shows a pen-and-ink-drawing of Katherine, wearing a crown. To the left and right of her is written: Sancta Katherina virgo. A label of the monastic library of Melk, with the old shelfmark, is pasted over the word ‘Sancta’. The inscription below says that the book belonged to Ortolfus, a priest from Rusbach, who donated it to the monastery of Melk.

https://manuscripta.at/images/AT/6000/AT6000-516/AT6000-516_VDS.jpg

Portrait V: Heloise d’Argenteuil (1096?-1164)

Heloise is best known for her correspondence and love affair with Abelard, but she was also a scholar in her own right. She was educated at the convent of Argentueil. Her uncle Fulbert, canon of Notre-Dame in Paris, wished to further her studies and entrusted his niece to the tuition of Abelard, who was known for his skills in dialectical argumentation. By all accounts, Heloise was a brilliant student. In the words of Abelard: “she stood out above all by reason of her abundant knowledge of letters […] making her famous throughout the kingdom”.16 However, as Abelard recounts, teacher and student were more interested in each other than in their study books.

https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b6000318d

Their affair caused a scandal. Abelard’s former teacher Roscelin of Compiègne wrote Abelard a letter full of reproach: “Not sparing the virgin entrusted to you, whom you should have taught as a student [..] you taught her not to argue but to fornicate.”17 The accusation implies that Abelard had been employed with the specific purpose to teach Heloise to argue.

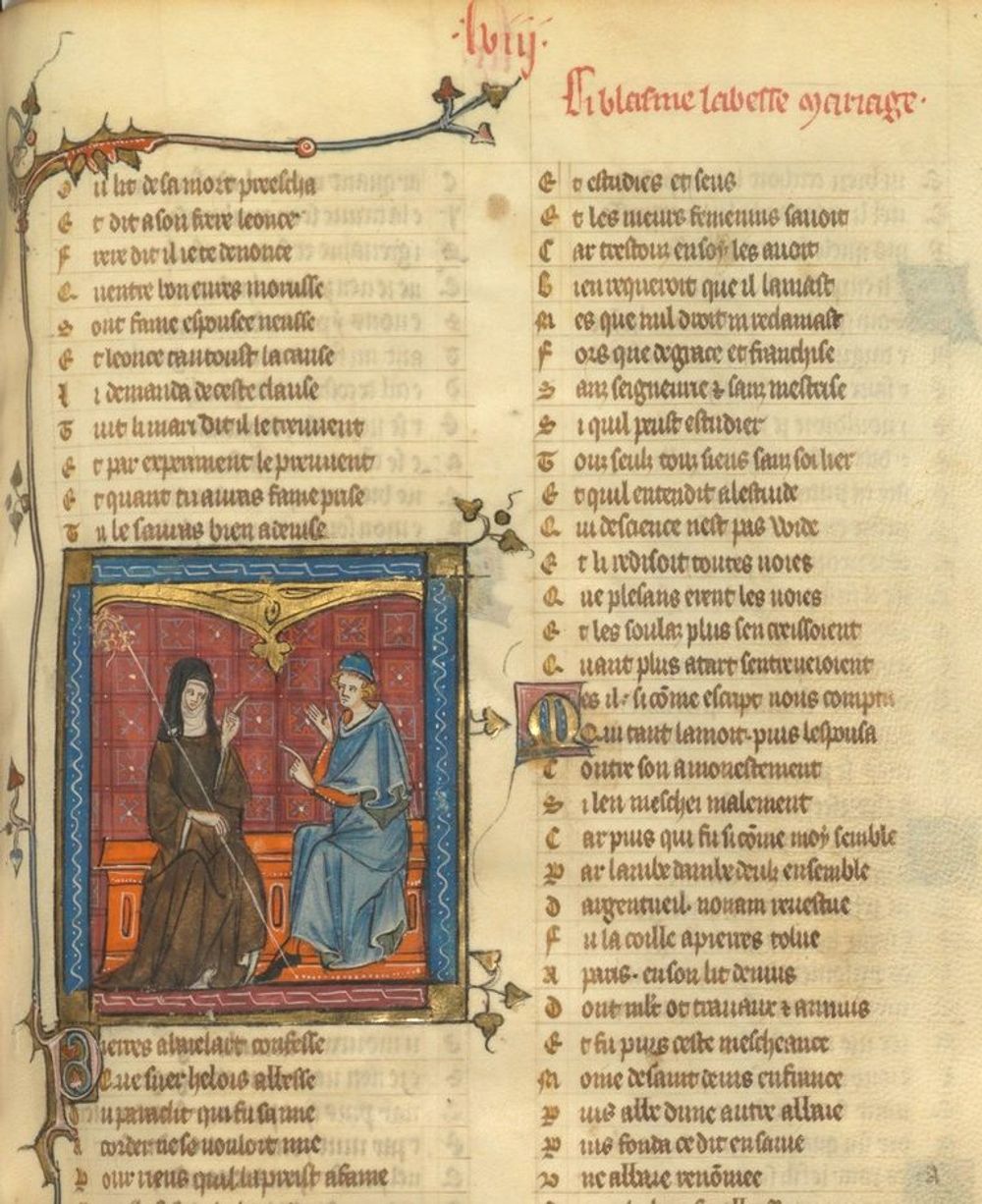

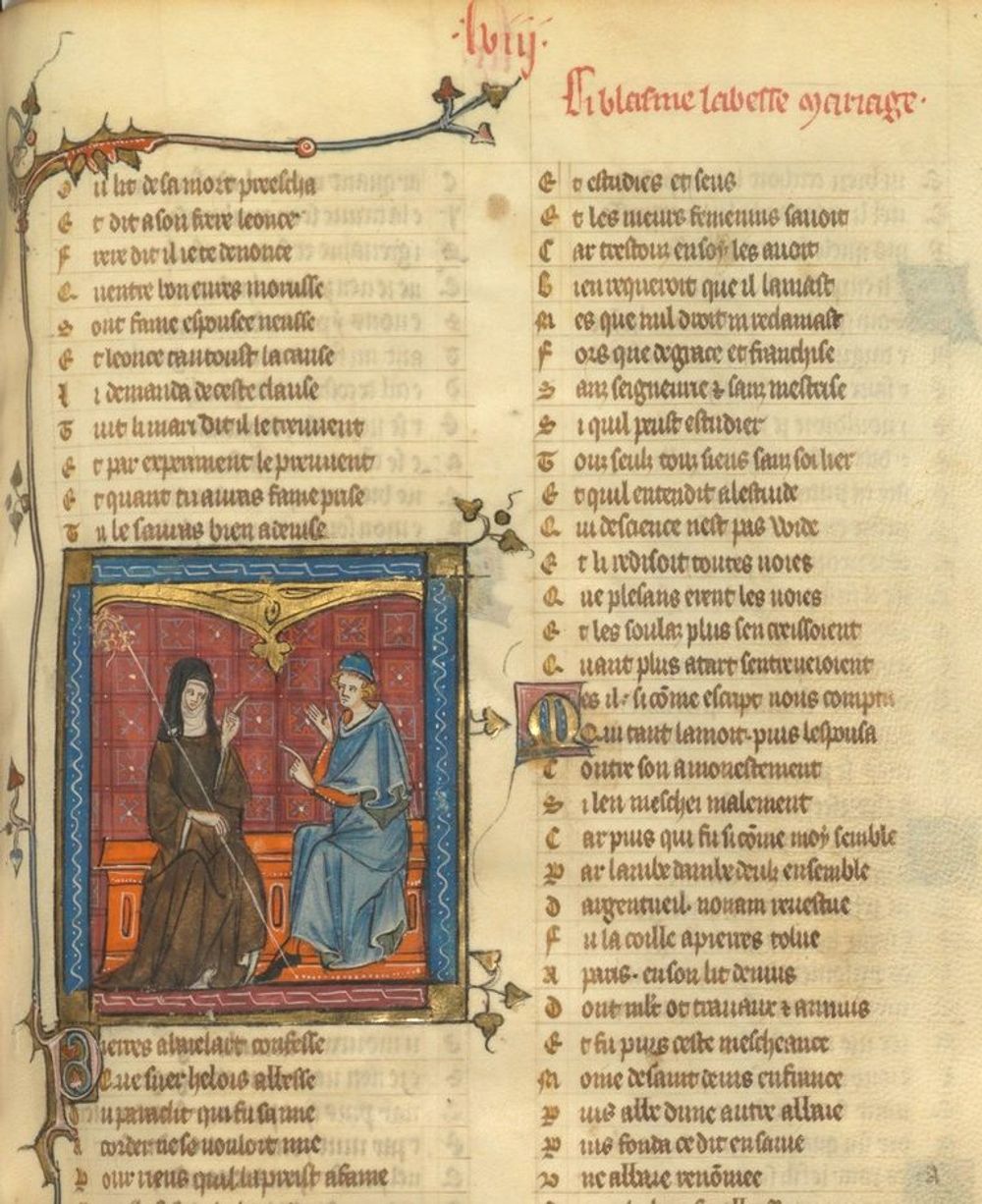

This miniature in a fourteenth-century manuscript of the Roman de la Rose shows Abelard and Heloise debating. Heloise is wearing a habit and a veil, while Abelard is dressed as a layman. The scene depicts the moment when Heloise has entered the convent of Argenteuil, and Abelard has come to visit her. The rubric reads: “Comment helouys labeesse entrodit pierres abalart”: “How Peter Abelard instructs Abbess Heloise”. The hand gestures in the miniature, however, rather indicate debate than instruction.18

http://initiale.irht.cnrs.fr/en/decor/78892

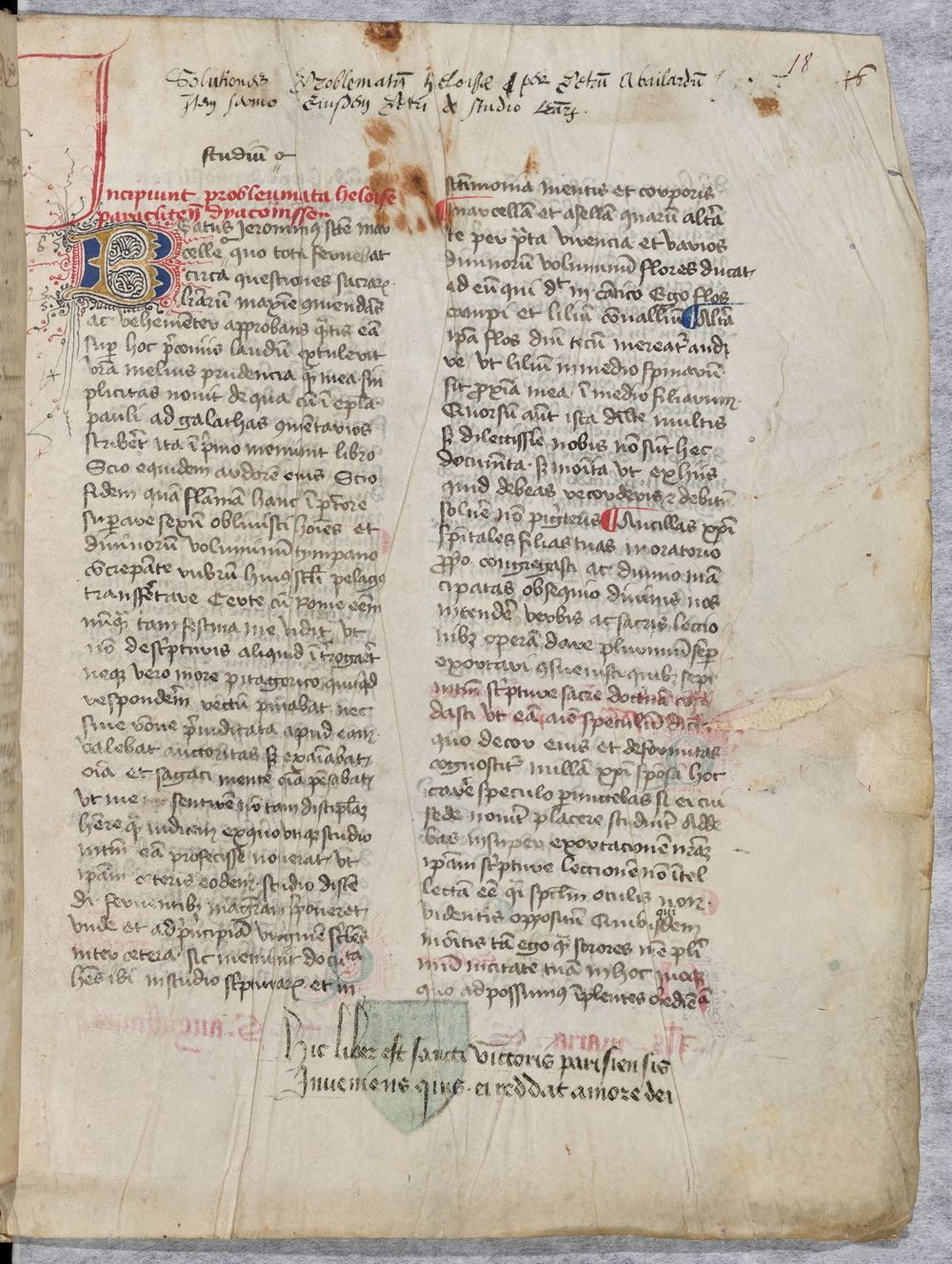

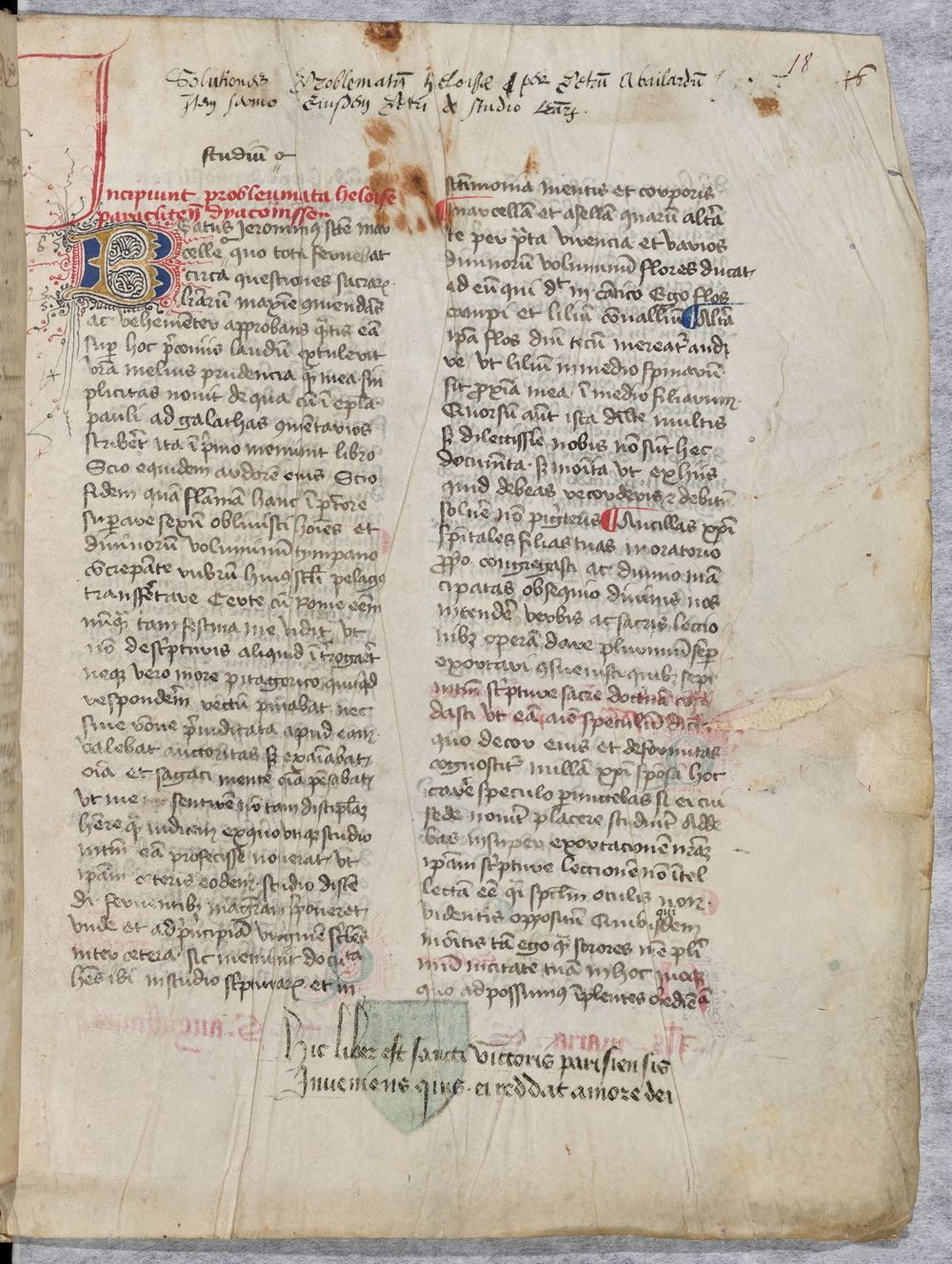

When the convent in Argenteuil closed in 1129, Abelard gave Heloise and the nuns the oratory of the Paraclete which he had built a few years earlier. Here, Heloise wrote the Problemata Heloissae, a collection of forty-two questions, which she and her sisters raised and Abelard answered. In the prefatory letter to the Problemata, Heloise wrote that she has followed the example of Marcella questioning Jerome. She quoted Jerome saying that Marcella was not so much his pupil but rather his judge.

Only two manuscripts with Heloise’s Problemata have survived. This manuscript, Paris, BnF. Lat. 14511, dates to the late fourteenth or early fifteenth century. The text opens on f. 18r with the words: “Here begin the Problemata of Heloise deaconess of the Paraclete”19. A title added above the text in a cursive hand turns the perspective around and attributes authorship to Abelard: “Answers to the questions of Heloise by Peter Abelard”.20 This section of the manuscript was copied for the humanist scholar Simon Plumetot (1371-1443), who collected texts written by Abelard. His predominant interest in Abelard may explain the added title at the top of the page. Plumetot donated this and other manuscripts related to Abelard to the abbey of St-Victor, where he had studied.21

https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b9068387d.r=14511?rk=21459;2

Abelard and Heloise are depicted in this initial S in a mid-thirteenth manuscript, Paris, BnF, lat. 2923. It marks the opening of Abelard’s autobiography The Story of My Misfortunes (Historia Calamitatum), in which he recounted the story of his love affair and subsequent spiritual friendship with Heloise. The figure on the left represents Abelard, the figure on the right, whose face has been erased, is believed to represent Heloise. They are both holding books. The manuscript not only contains Abelard’s autobiography, but also his correspondence with Heloise. Go to the manuscript portrait of Paris, BnF, lat. 2923 to read more about the appreciative remarks that one famous humanist reader added to Heloise’s letters, admiring both her style of writing and her demeanor. Here you will also find an hypothesis as to why Heloise’s face has been rubbed away.

https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b84386206

In the late thirteenth century, the poet and cleric Jean de Meun (d. 1305) discovered the letters of Heloise and Abelard. He was much impressed by Heloise’s erudition and in particular by her arguments against marriage. He retold their love story in his continuation of the Roman the la Rose. This miniature in manuscript Paris, BnF, Département des manuscrits Français, ms. 1560, containing the Roman de la Rose, shows Heloise and Abelard debating love and marriage. The text below the miniature reads: “Peter Abelard admits that sister Heloise, abbess of the Paraclete, would not for anything agree to his marying her.” The column on the right lists Heloise’s arguments against marriage. Jean de Meun concludes: “By my soul, I do not think there has ever been such a woman since. I believe that her erudition enabled her better to conquer and subdue her nature and its feminine ways . If Peter [Abelard] had believed her, he would never have married her.”22

https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b6000318d

The five women we have encountered in this portrait gallery were remembered for their skills in argumentation and for participating in debates, both in private and in public. But did Marcella, Eulalia, Gundrada, Katherine and Heloise really engage in disputations, or did their biographers and correspondents imagine and idealize their performance and skills? In some cases, we cannot be certain. Yet it is important to note that martyrdom narratives, letters, poems and saints’ lives inspired poets, authors and miniaturists to at least entertain the possibility of women engaging in disputation, amongst themselves, but also with men. This may have opened up possibilities for women to actually participate in debates, in spite of the apostle Paul’s restrictions on women teaching and speaking in public.

Sources used for this contribution:

Primary sources

- Abelard, Historia calamitatum, ed. J. Monfrin (Paris, 1967, 3rd edition)

- Jerome, Commentaria in epistolam ad Galatas, PL 26, 307-438

- Jerome, Ep. 127 (Ad Principiam virgins de vita sanctae Marcellae), ed. I. Hilberg, CSEL 56 (Vienna, Leipzig, 1918), p. 145-156, translation https://www.newadvent.org/fathers/3001127.htm

- Guillaume de Lorris and Jean de Meun, The Romance of the Rose. Translated with an introduction and notes by Frances Horgan (Oxford World’s Classics, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1994, reissued 2008)

- Radbert of Corbie (Paschasius Radbertus), Vita Adalhardi, ed. PL 120 (Paris, 1852), 1507-1556

- Passio sanctae Katharinae Alexandriensis, https://la.wikisource.org/wiki/Passio_S._Katharinae

- Prudentius, Peristephanon liber, ed. and trans. H. J. Thomson, LCL 102, new edn (Cambridge-Mass, London, 1961), pp. 98-345.

- Roscelin, Epistola ad Abaelardum, PL 178 (Paris, 1855), 357-372.

- The Letters of Abelard and Heloise. Translated with an introduction and notes by Betty Radice, revised by Michael T. Clanchy (Penguin Classics, London and New York: Penguin Books, 2003)

Secondary literature

- Cain, Andrew, ‘Rethinking Jerome’s portraits of holy women’, in Andrew Cain, Joseph Lössl, Jerome of Stridon. His Life, Writings and Legacy, pp. 47-57.

- Castiñeiras, Manuel, ‘Patrons, Artists and Audiences in the Making of Visual Culture in Medieval Iberia (eleventh – thirteenth centuries)’, in J. Muñoz-Basols, L. Lonsdale, M. Delgado (eds.), The Routledge Companion to Iberian Studies (London: Taylor and Francis, 2017), pp. 118-133

- Garrison, Mary, ‘The social world of Alcuin: nicknames at York and at the Carolingian court’, in L. A. J. R, Houwen, A. A. MacDonald (eds.), Alcuin of York. Scholar at the Carolingian Court (Groningen, 1998), p. 59-79

- Jenkins, J. and K. J. Lewis (eds.), St Katherine of Alexandria: Texts and Contexts in Western Medieval Europe (Medieval Women: Texts and Contexts 8, Turnhout: Brepols Publishers, 2003).

- Mews, Constant J., ‘Interpreting Abelard and Heloise in the fourteenth and early fifteenth centuries. The criticisms of Christine de Pizan and Jean Gerson’, in P. J. J. M. Bakker, E. Faye, & C. Grellard (eds.), Chemins de la pensee medievale. Etudes offertes a Zenon (Turnhout: Brepols Publishers, 2002), pp. 709-724

- Mews, Constant J., Abelard and Heloise. Great Medieval Thinkers (Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, 2005)

- Nelson, Janet L., ‘Gendering Courts in the Early Medieval West’, in L. Brubaker, J. Smith (eds), Gender in the Early Medieval world, East and West, 300-900 (Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2004), pp. 185-198.

- Renswoude, Irene van, The Rhetoric of Free Speech in Late Antiquity and the Early Middle Ages (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2019)

- Scheck, Helene, Reform and Resistance: formations of female subjectivity in early medieval ecclesiastical culture, SUNY Series in Medieval Studies 241 (New York, State University of New York, 2008)

- Jenkins, J. and K. J. Lewis (eds.), St Katherine of Alexandria: Texts and Contexts in Western Medieval Europe (Medieval Women: Texts and Contexts 8, Turnhout: Brepols Publishers, 2003), pp. 19-35.

- Walsh, Christine, The Cult of St. Katherine of Alexandria in Early Medieval Europe (Aldershot and Burlington: Ashgate, 2007)

Contribution by Irene van Renswoude. I thank Janneke Raaijmakers for her critical reading and always excellent suggestions for my contributions.

Cite as, Irene van Renswoude, “Women and disputation”, The art of reasoning in medieval manuscripts (Dec 2020), https://art-of-reasoning.huygens.knaw.nl/women-disputation. ↑

Jerome, Ep. 127.7, ed. Hilberg, p. 151. ↑

Jerome, Ep. 127.7, ed. Hilberg, p. 151, transl. Cain, 2009, p. 54. ↑

Jerome, Commentaria in epistolam ad Galatas, prologue, PL 26, 331b-332b. ↑

Jerome, Ep. 127.9, ed. Hilberg, p. 152, translation https://www.newadvent.org/fathers/3001127.htm. ↑

Jerome, Ep. 127.10, ed. Hilberg, p. 153. ↑

Prudentius, Peristephanon 3, ed. Thomson, pp. 122-130. ↑

van Renswoude, 2019, pp. 21-40. ↑

Scheck, 2008, p. 57. ↑

Radbert of Corbie, Vita Adalhardi, c. 33. ↑

Nelson, 2004, p. 191. ↑

Garrison, 1998. ↑

Walsh, 2007, p. 10 ↑

Passio Catherinae, 16 ↑

Castiñeiras, 2017, 127. ↑

Abelard, Historia calamitatum, ed. Monfrin, 71.286-288. ↑

“non argumentari, sed eam fornicari docuisti”. Roscelin, Epistola ad Abaelardum, PL 178: 369C, transl. Mews, 2005, 58. ↑

See Clanchy, Radice, 2003 for the translation of the rubric and interpretation of the hand gestures. ↑

“Incipiunt problemata heloise paraclitensis dyaconisse”. ↑

“Solutiones problematum heloise per petrum abailardum”. ↑

Mews, 2002, p. 711. ↑

transl. Horgan, 2008, p. 135 ↑

Next Read:

Next Read: