Reasoning through syllogisms

How do propositions relate to syllogisms?1

Propositions and syllogisms are the foundations of medieval logical reasoning. Derived from the writings of Aristotle – notably the On interpretation and the Prior analytics– in the translations of Apuleius and Boethius, propositions and syllogisms provided a methodology for constructing a logical argument.

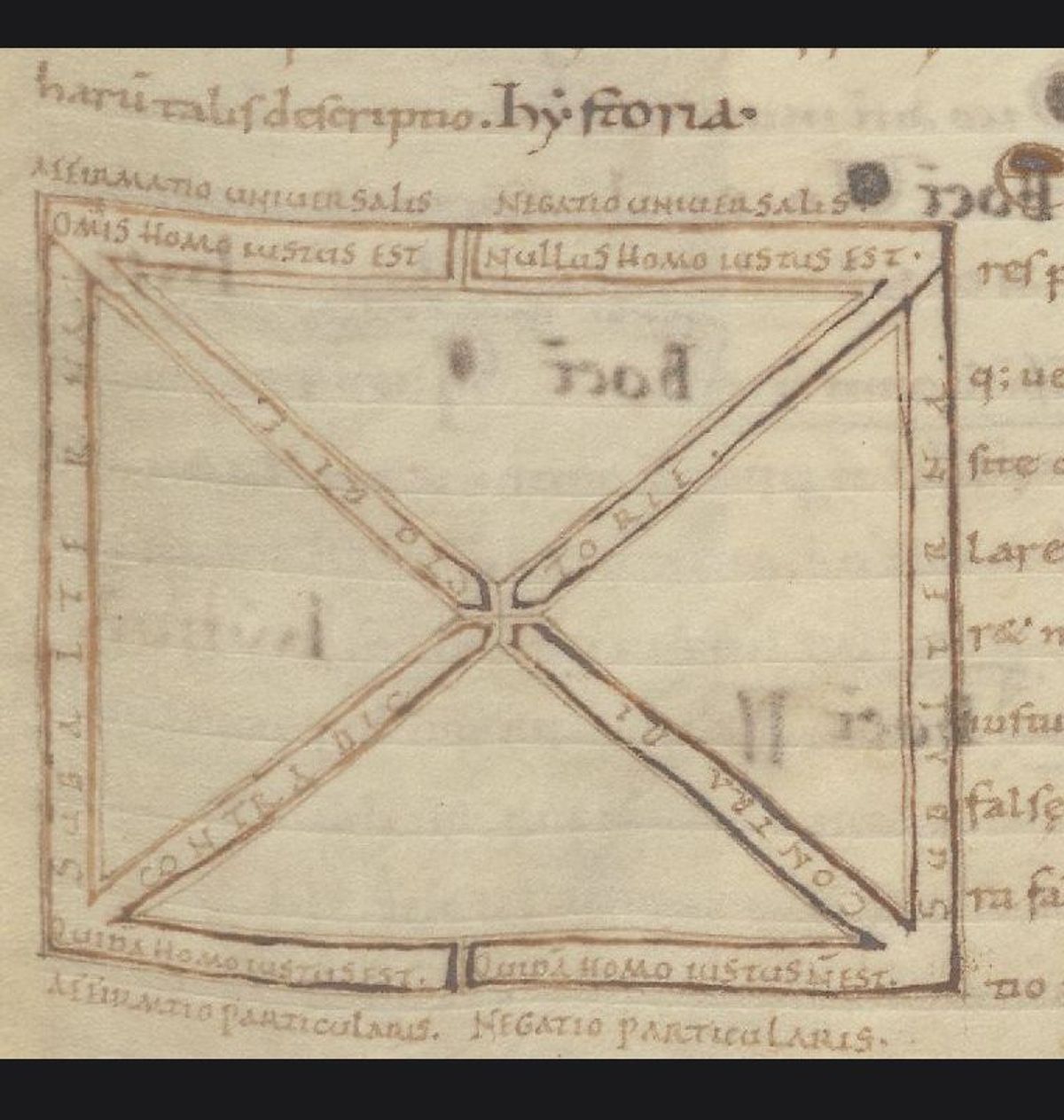

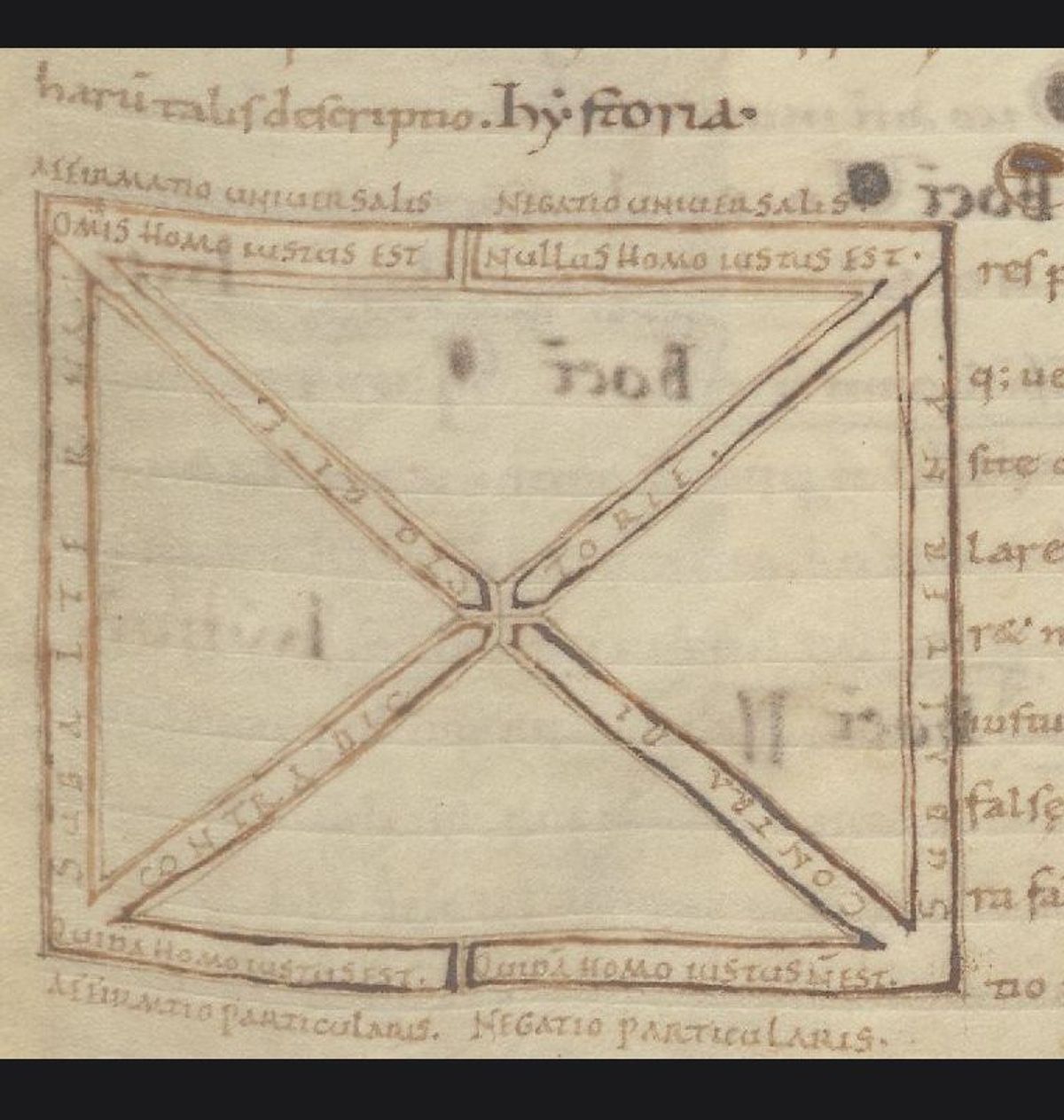

The square of opposition allows you to relate propositions that have the same subject and predicate. But what happens when you have more than two terms, or want to relate propositions with different subjects or predicates? A syllogism is another way of relating propositions and formally consists of two propositions and a conclusion. One term is common to both propositions (or premise) and to the conclusion. By reasoning from what is common between the premises you can come to a reasoned conclusion. For example, from the propositions ‘Every horse is an animal’ and ‘Some horses are white’, we can make the following conclusion: ‘Therefore, some animals are white’.

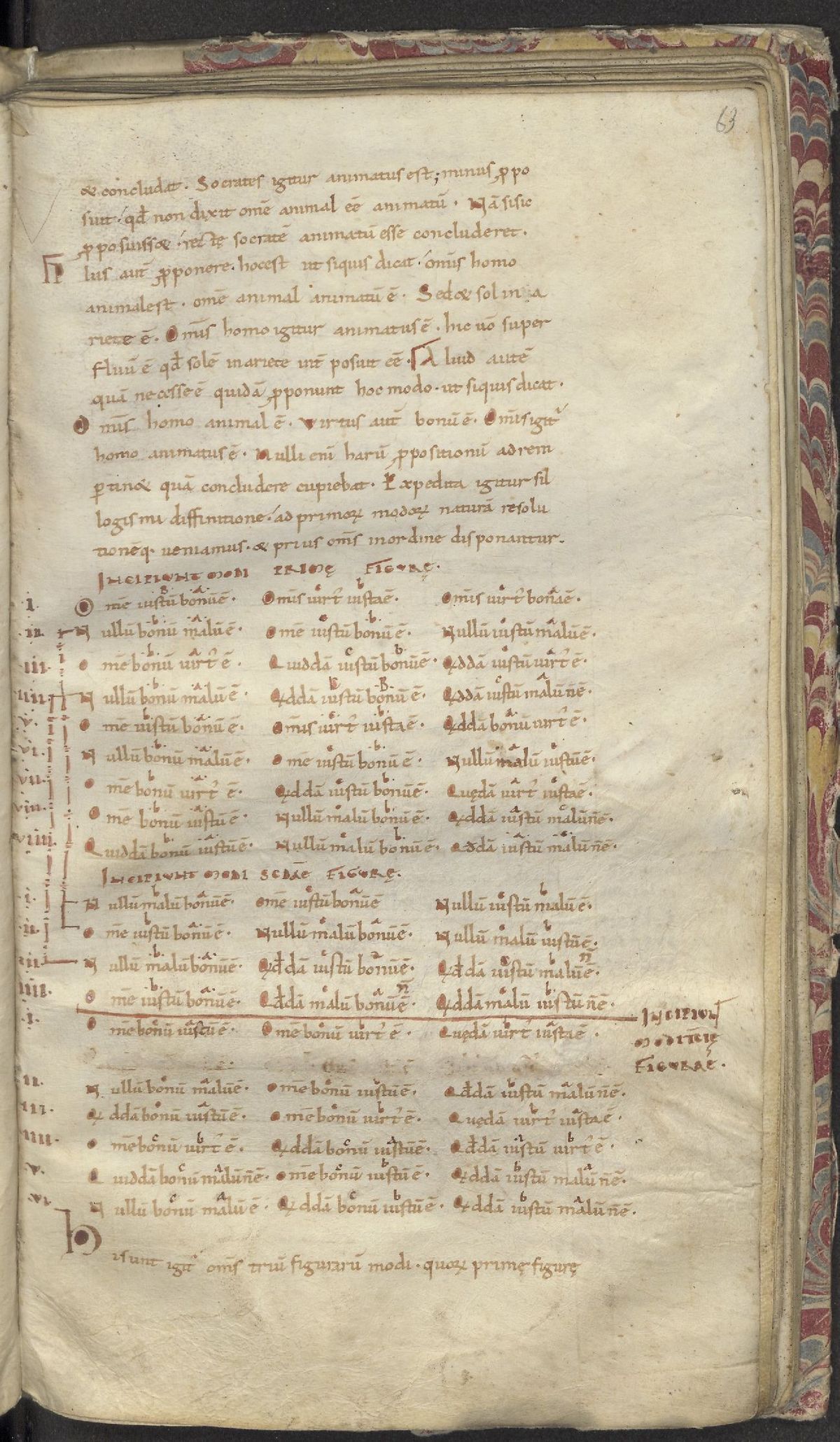

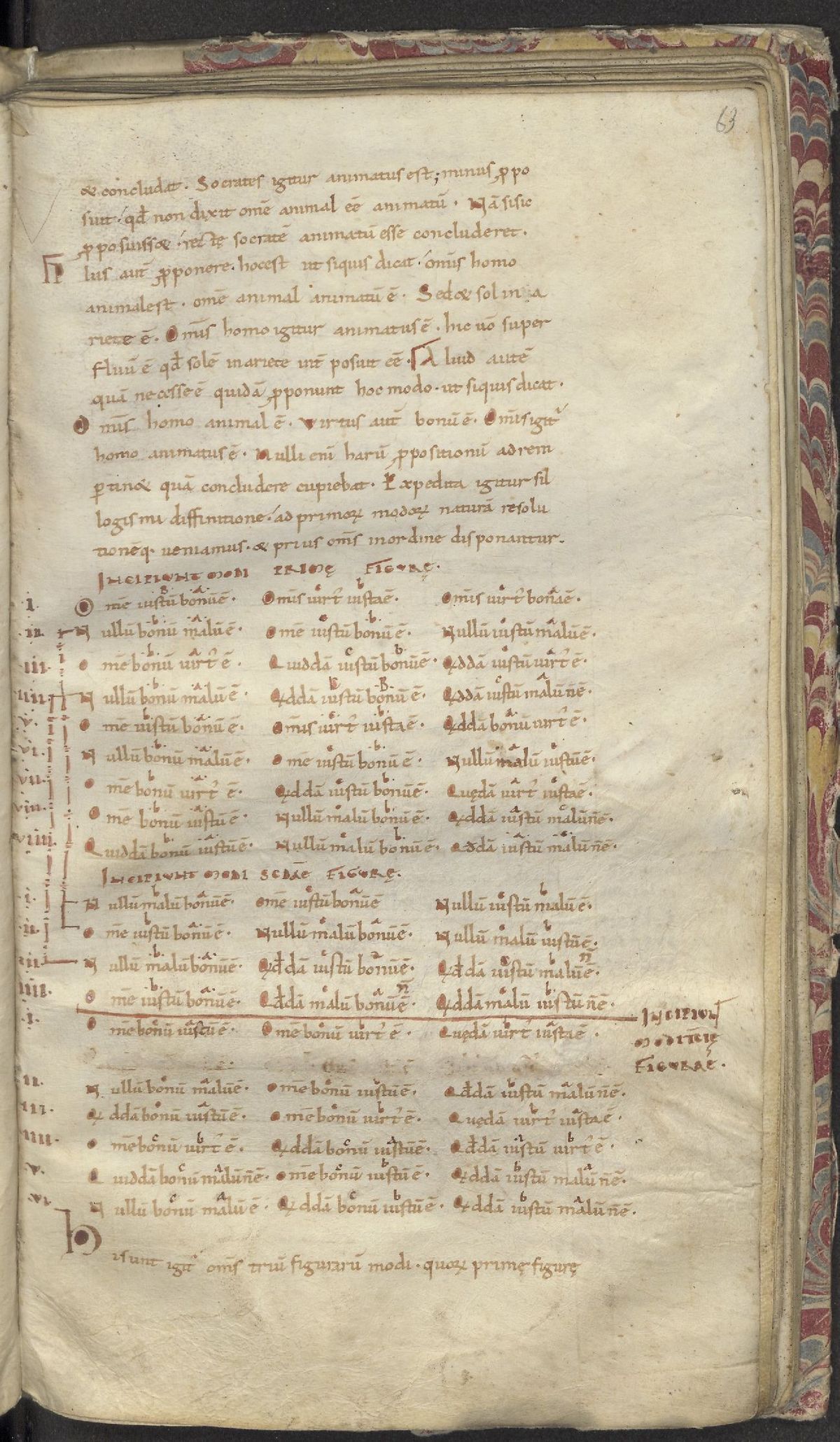

Moods of syllogisms

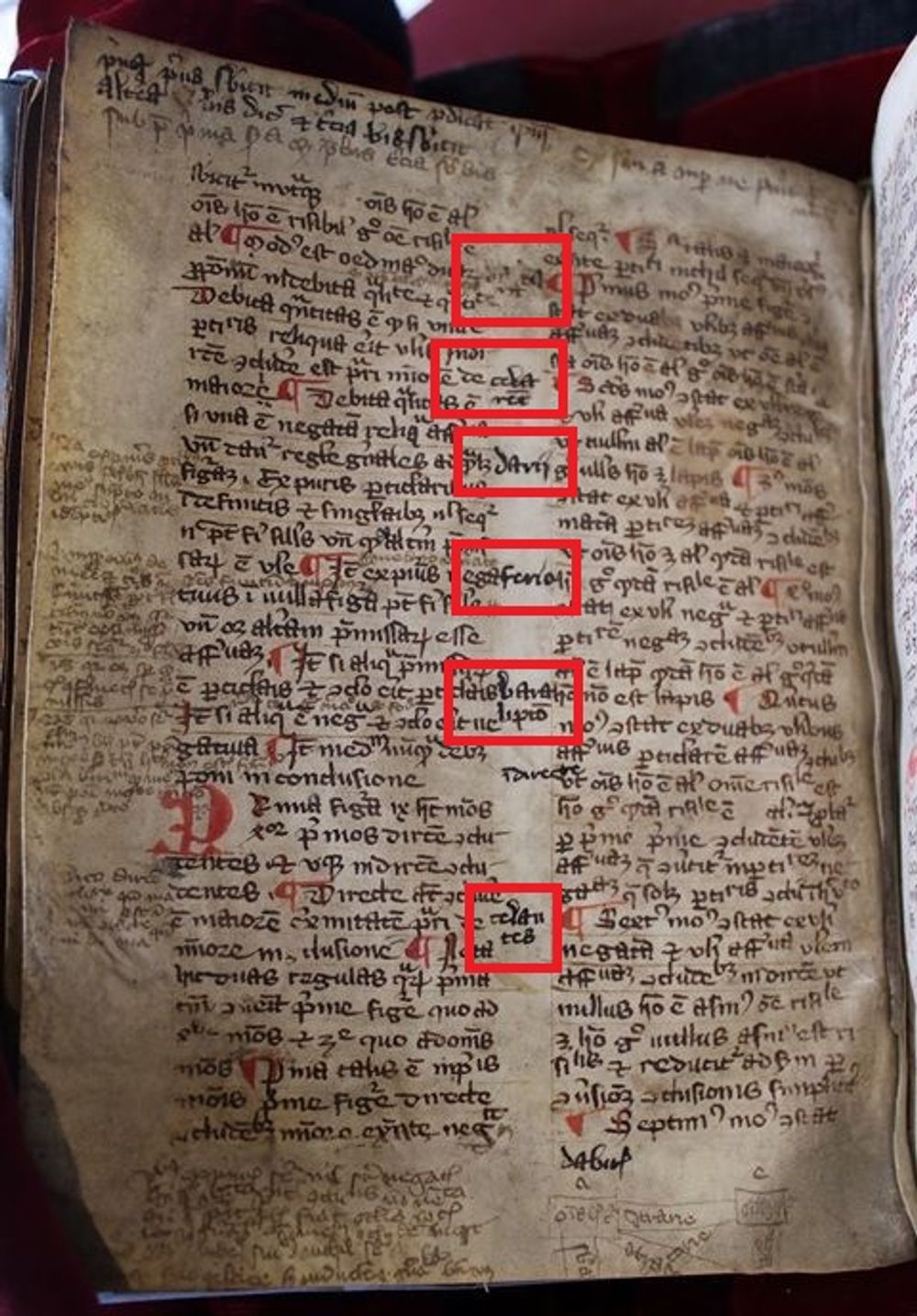

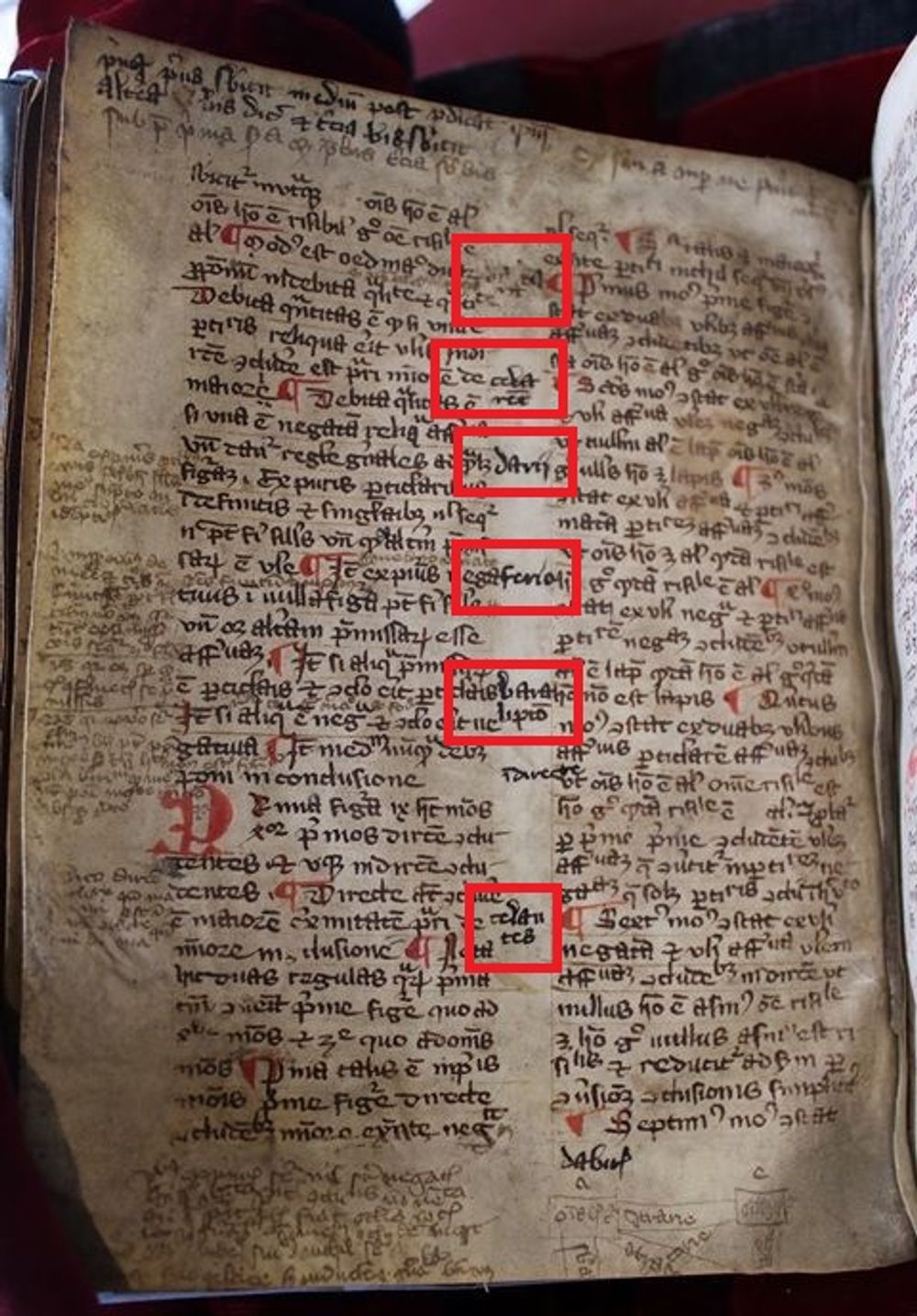

Aristotle identified nineteen different ‘moods’ or patterns of syllogisms, which he divided into three ‘figures’, or groupings, with each figure involving a different arrangement of subject and predicate in the premise. In this manuscript (Leiden UB, BPL 84, f. 63r, a copy of Boethius’s Introductio ad syllogismos categoricos), we can see an exposition of the moods of first figure syllogisms. They are numbered alongside the text in the inner margin and red brackets and rubrics are used to distinguish them. The first example of these syllogisms reads: “All that is just is good. All that is virtuous is just. Therefore, all that is virtuous is good.” This syllogism joins two universal affirmative propositions (‘all that is just is good’ and ‘all that is virtuous is just’) and deduces the conclusion ‘all that is virtuous is good’.

Remembering the moods of syllogisms

In order to remember the nineteen moods of syllogisms, medieval logicians came up with a short verse which ‘encoded’ the details of each of the three figures:

Barbara Celarent Darii Ferio Baralipton

Celantes Dabitis Fapesmo Friesomorum

Cesare Cambestres Festino Barocho Darapti

Felapto Disamis Datisi Bocardo Ferison

To understand how this verse worked let us look at our first example of the first figure:

“All that is just is good. All that is virtuous is just. Therefore, all that is virtuous is good.” This syllogism consists of two universal affirmative premises and a universal affirmative conclusion. This syllogism is represented by the word ‘Barbara’, where the three vowels ‘a, a, a’ indicate that this is a syllogism made up of three universal affirmatives (represented by ‘a’, taken from ‘affirmo’).

In ‘Celarent’, on the other hand, the vowel ‘e’ represents a universal negative (‘no x is y’, taken from ‘nego’). A syllogism represented by ‘Celarent’, is made up of a universal negative, a universal affirmative, and a universal negative conclusion. For example: “No cat is a horse. Every tiger is a cat. Therefore, no tiger is a horse.” Meanwhile, the vowels i and o represent the particular affirmative (’some x is y’) and the particular negative (‘some x is not y’) respectively (with i taken from ‘affirmo’ and o from ‘nego’).

An influential account of the moods of the syllogisms, popularizing this verse, is found in Peter of Spain’s Summulae. In this manuscript, Paris, BnF, MS lat. 16611, f. 14v, given to the Sorbonne by the thirteenth-century master, Gerard d’Abbeville, the names of the syllogisms (“<Barbara> [erased], Celarent, Darii, Ferio, Baralipton, Celantes”) have been added in the space between the two columns of text. Here these names do double-duty; they remind the reader of the mnemonic verse, but they also indicate where the description of each mood can be found in the text.

https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b90768515

Playing with syllogisms I: Leiden UB, BPL 88

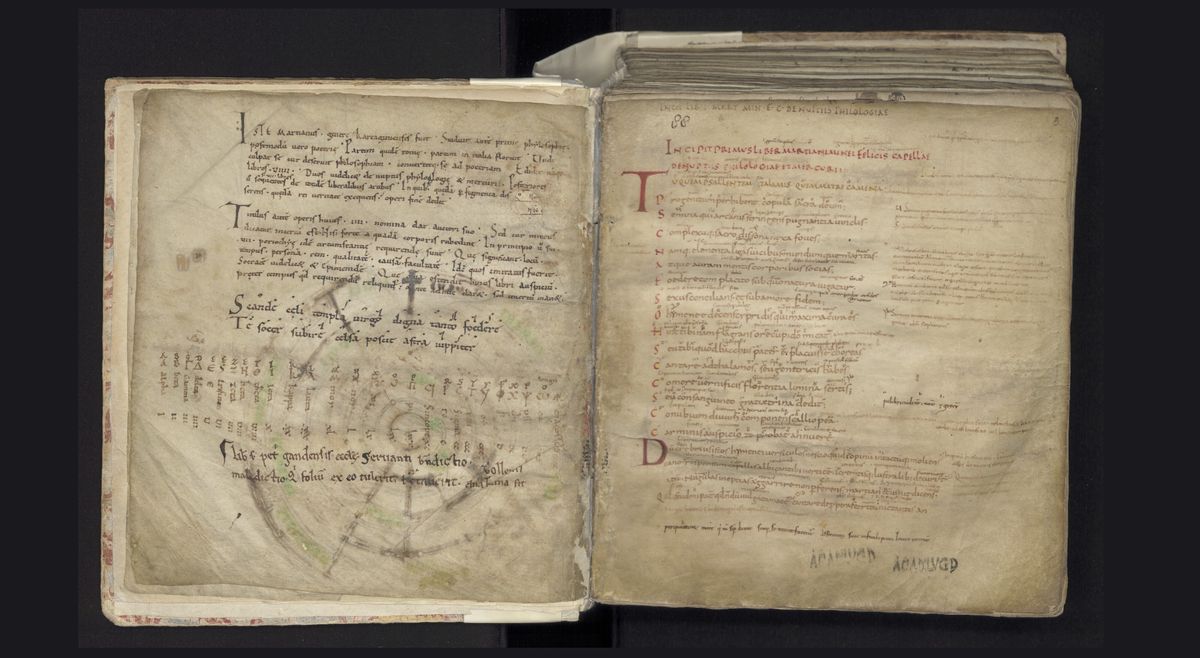

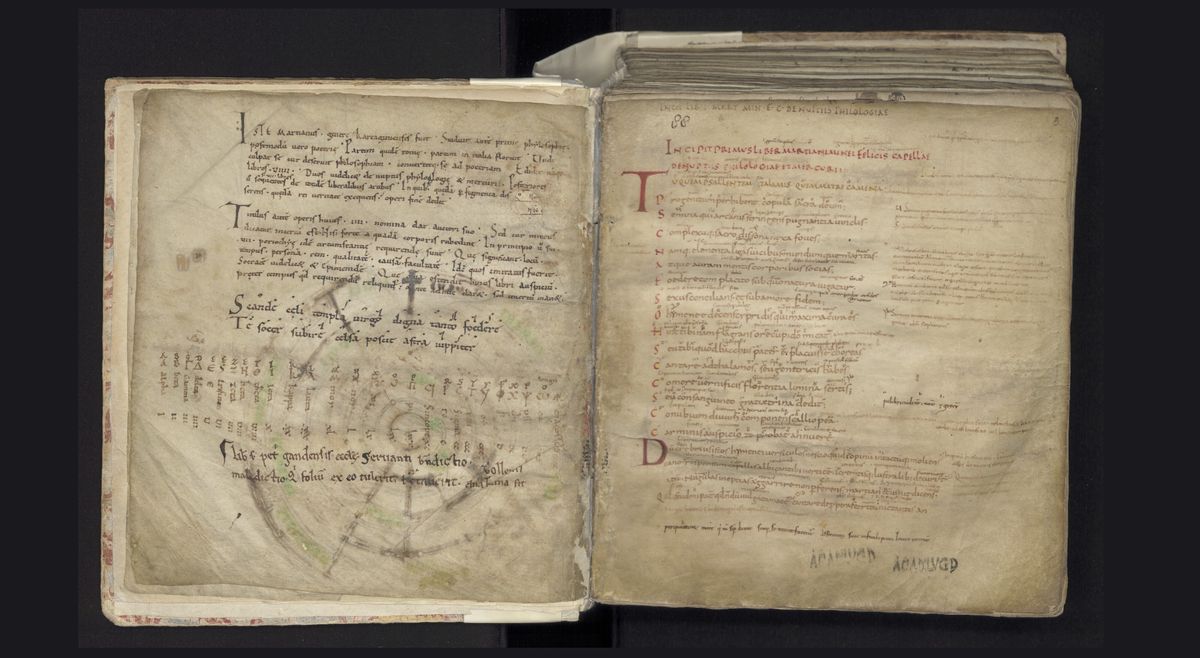

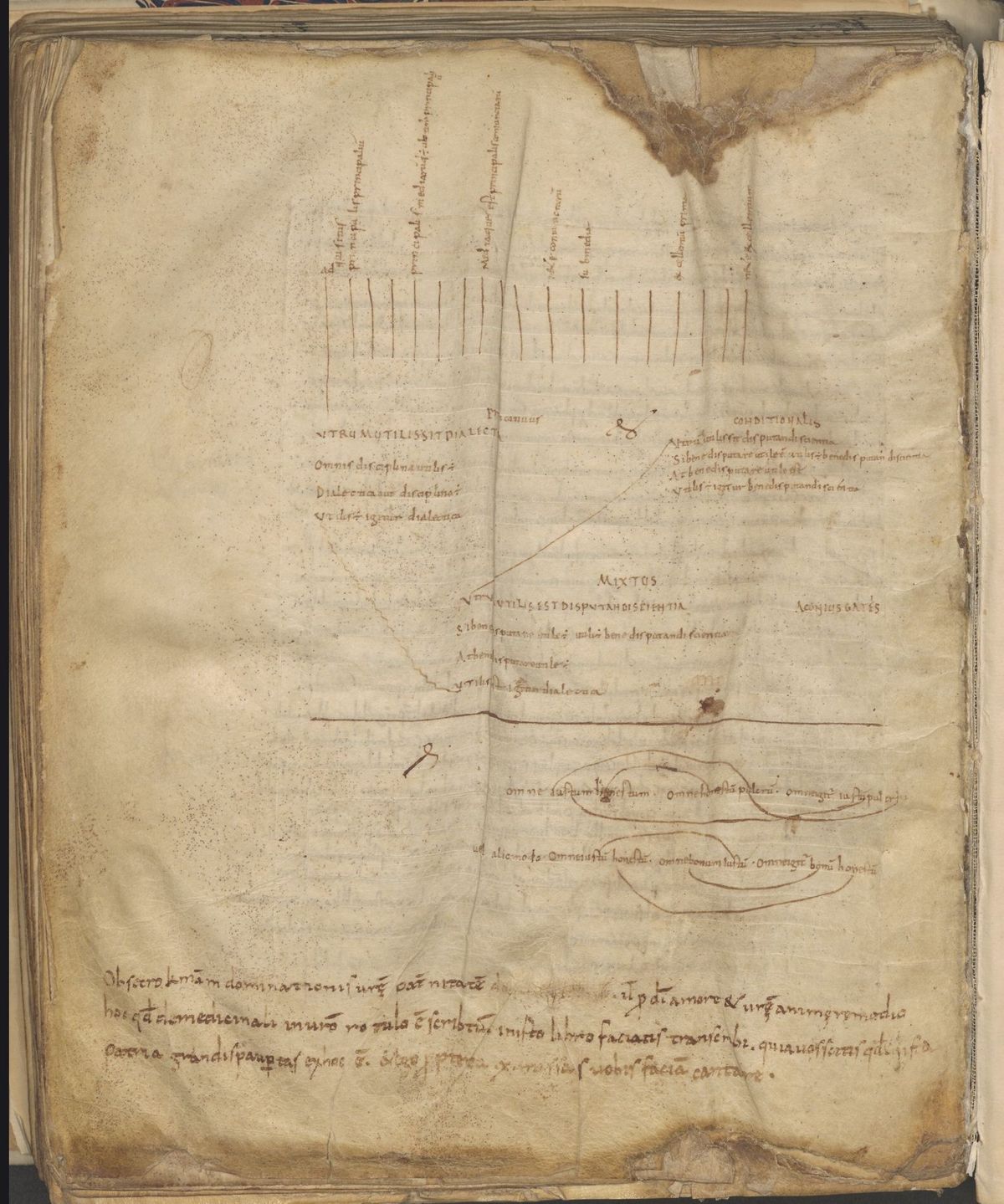

A bifolium (ff. 1-2) was attached to the ninth-century portion of manuscript Leiden, UB, BPL 88

as a set of flyleaves. We know it became appended to this manuscript (which contains Martianus Capella’s De nuptiis Philologiae et Mercurii) by the eleventh century at the latest, as on f. 2v an eleventh-century hand has added an ‘accessus’, a short introductory text, adding detail about Martianus and his writings, suggesting that by this point the bifolium and the rest of the manuscript were joined.

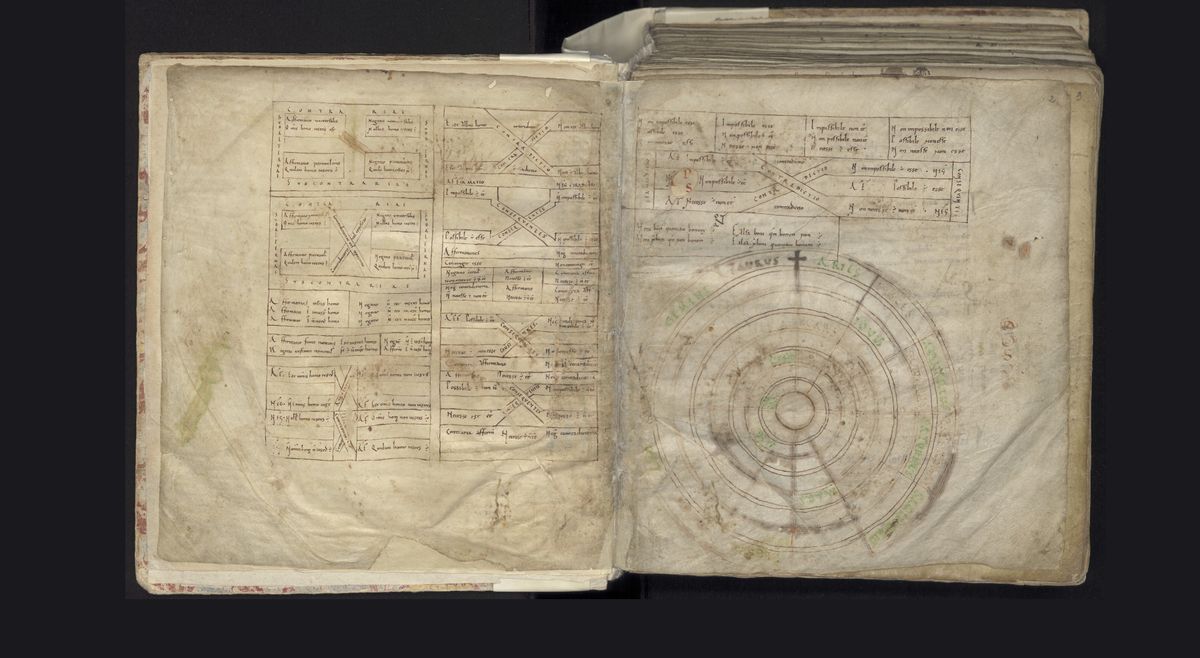

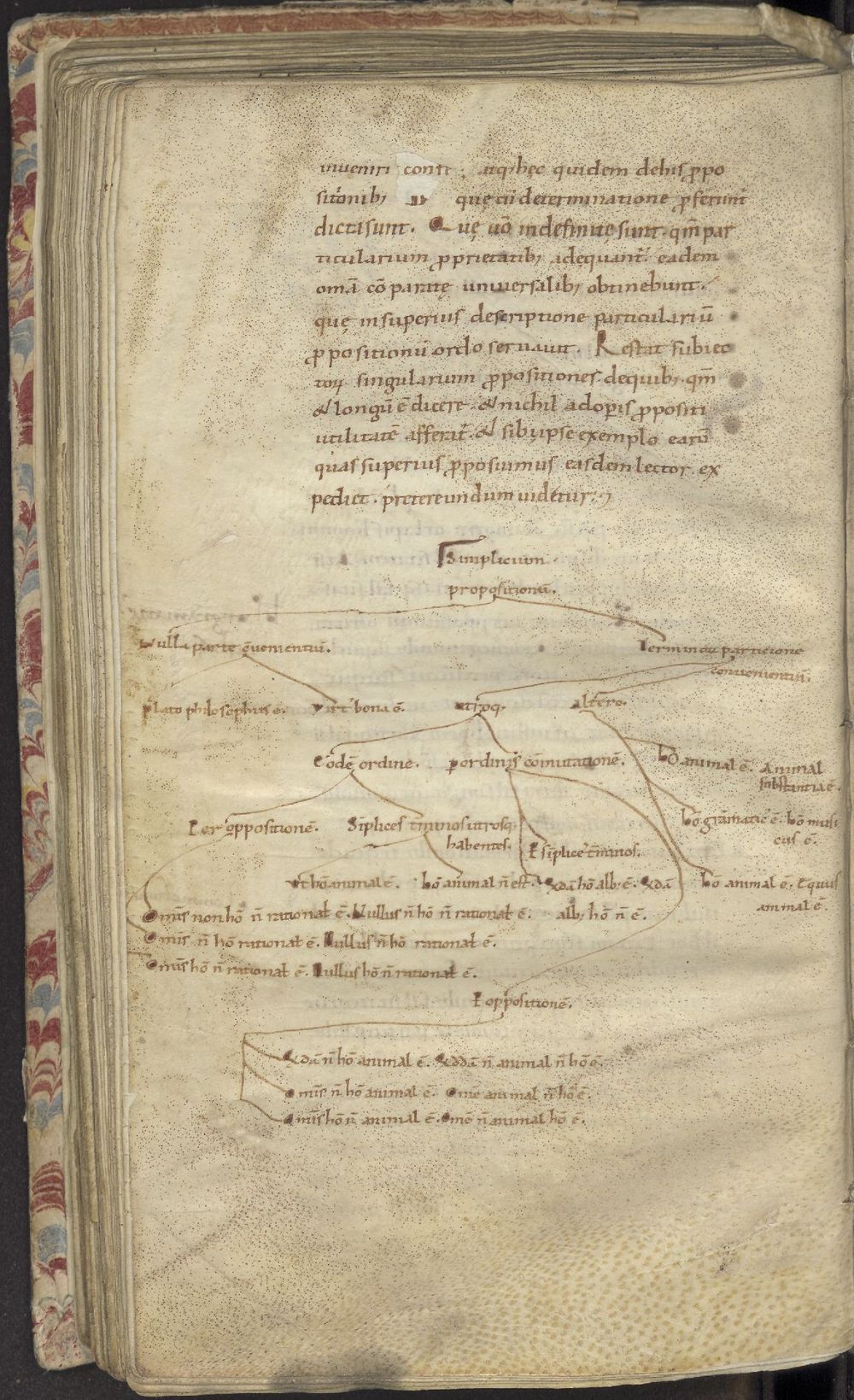

On ff. 1v-2r a scribe has added a series of ‘squares of oppositions’ and syllogisms. At first glance these look as though the scribe is experimenting with the possibilities of the ‘square of opposition’, plugging in various options at random. However, when we look closely at the content we find that the collection of schemes is far from haphazardly arranged. All of these sets of propositions can be found in Boethius’s first commentary on his translation of Aristotle’s De interpretatione (= Peri Hermeneias). Compare manuscript Leiden, UB, BPL 25 where these same sets of propositions (with the exception of the last) are found in the margins. The bifolium is, effectively, a diagrammatic summary of De interpretatione!

Why did the scribe gather all these sets of propositions into one place? Was he a student, making a medieval ‘crib sheet’, looking to memorise all the propositions, and perhaps wanting to have all the schemes to hand as he worked his way through Boethius’s complex text? Another possibility is that this bifolium was a draft sheet for a scribe; the fact that the second scheme on f. 1v duplicates and corrects the content of the first suggests that this sheet could represent ‘work in progress’. The unfinished zodiacal scheme on f. 2r might lead us to the same conclusion. Schemes were not easy to plan and draw, and draft sheets must have been made, although they rarely survive.

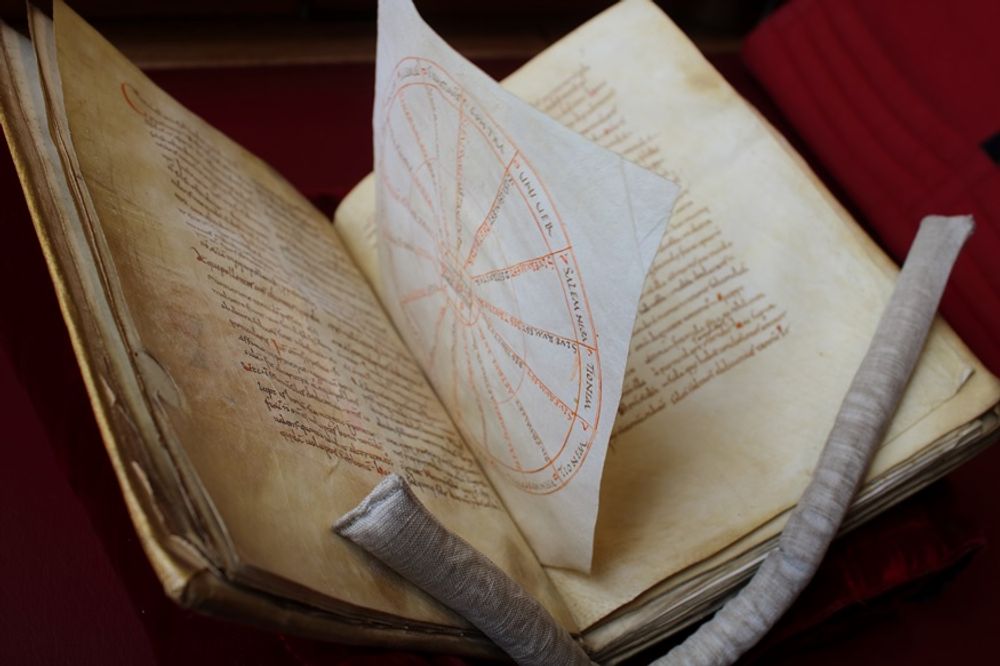

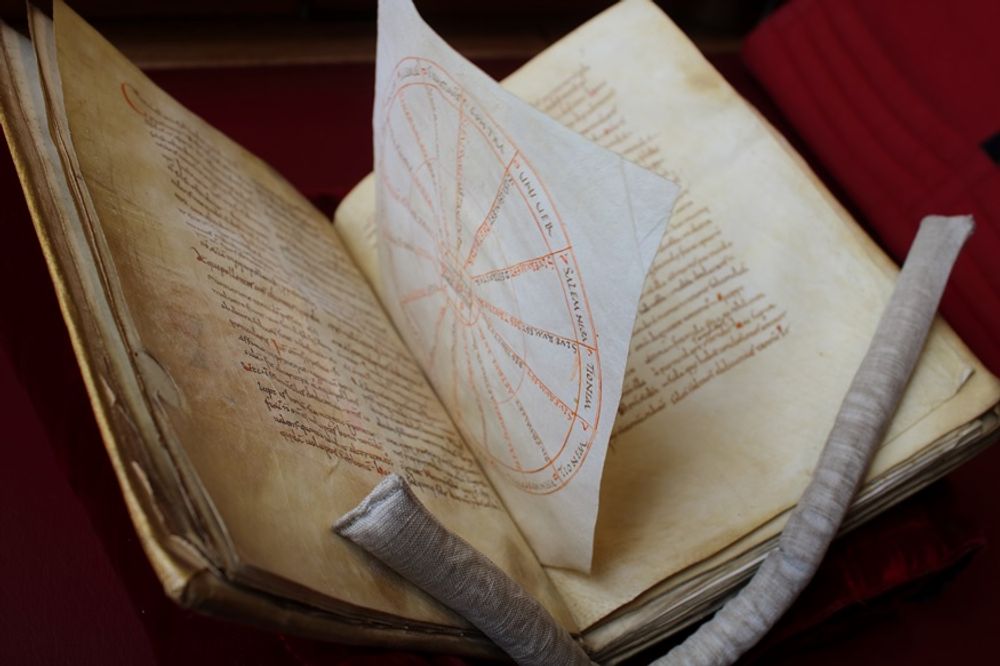

Playing with syllogisms II: Leiden UB, BPL 139B

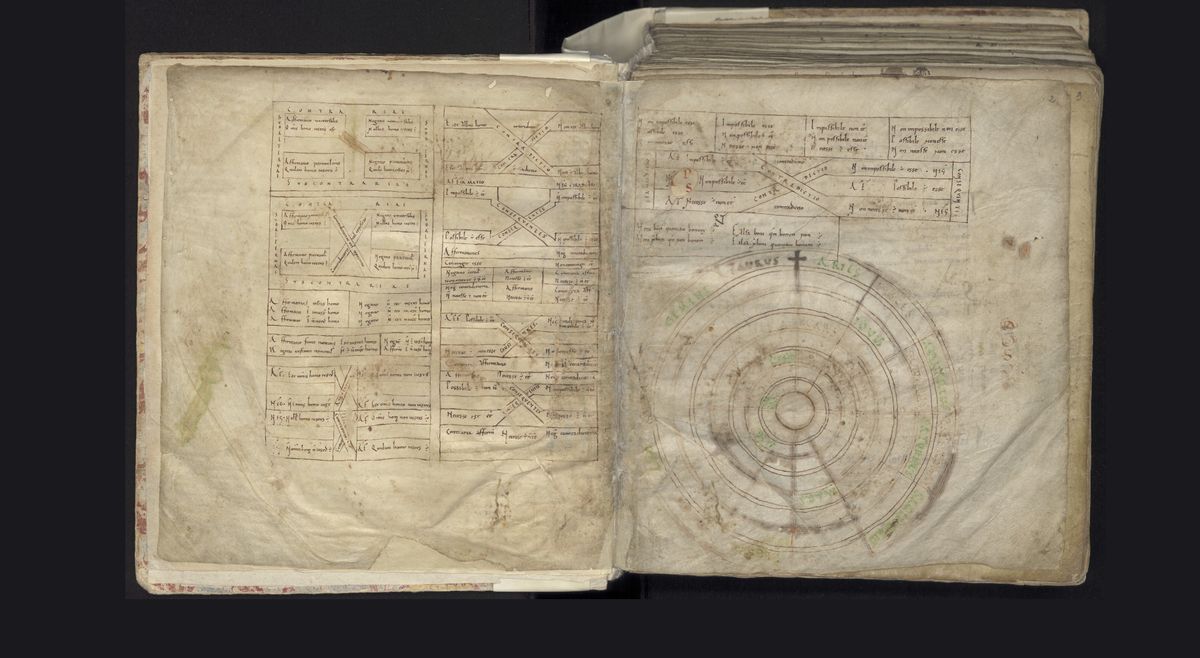

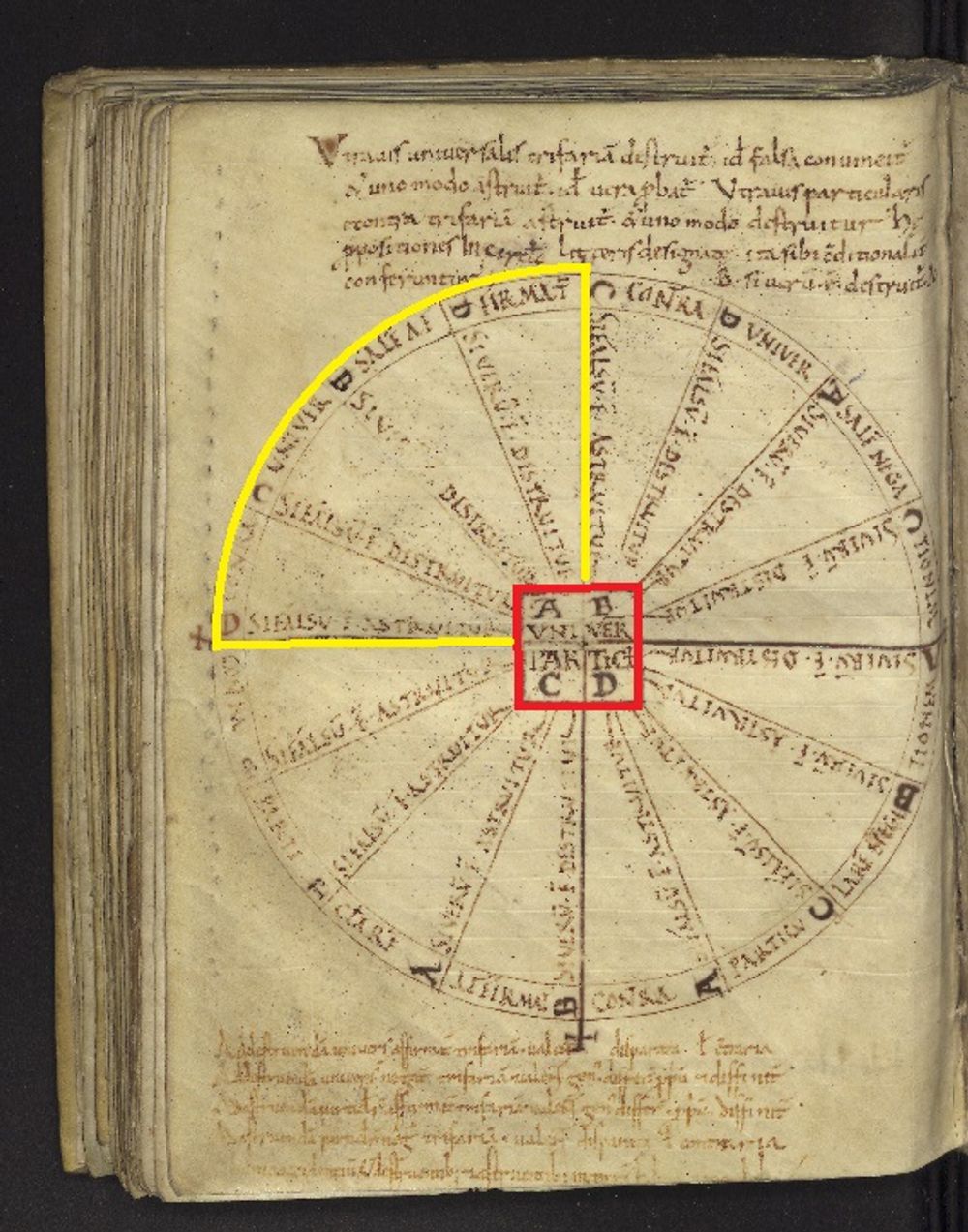

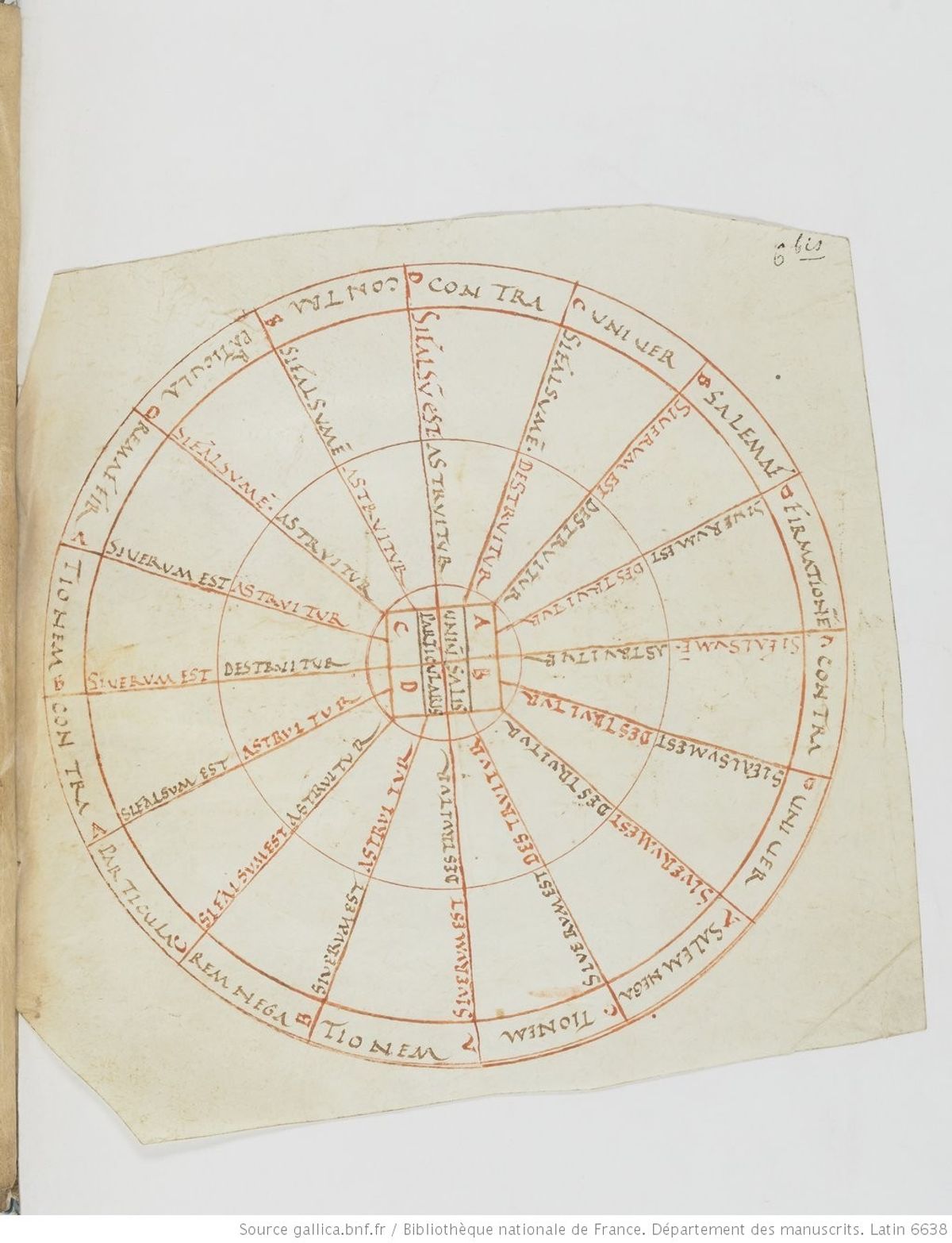

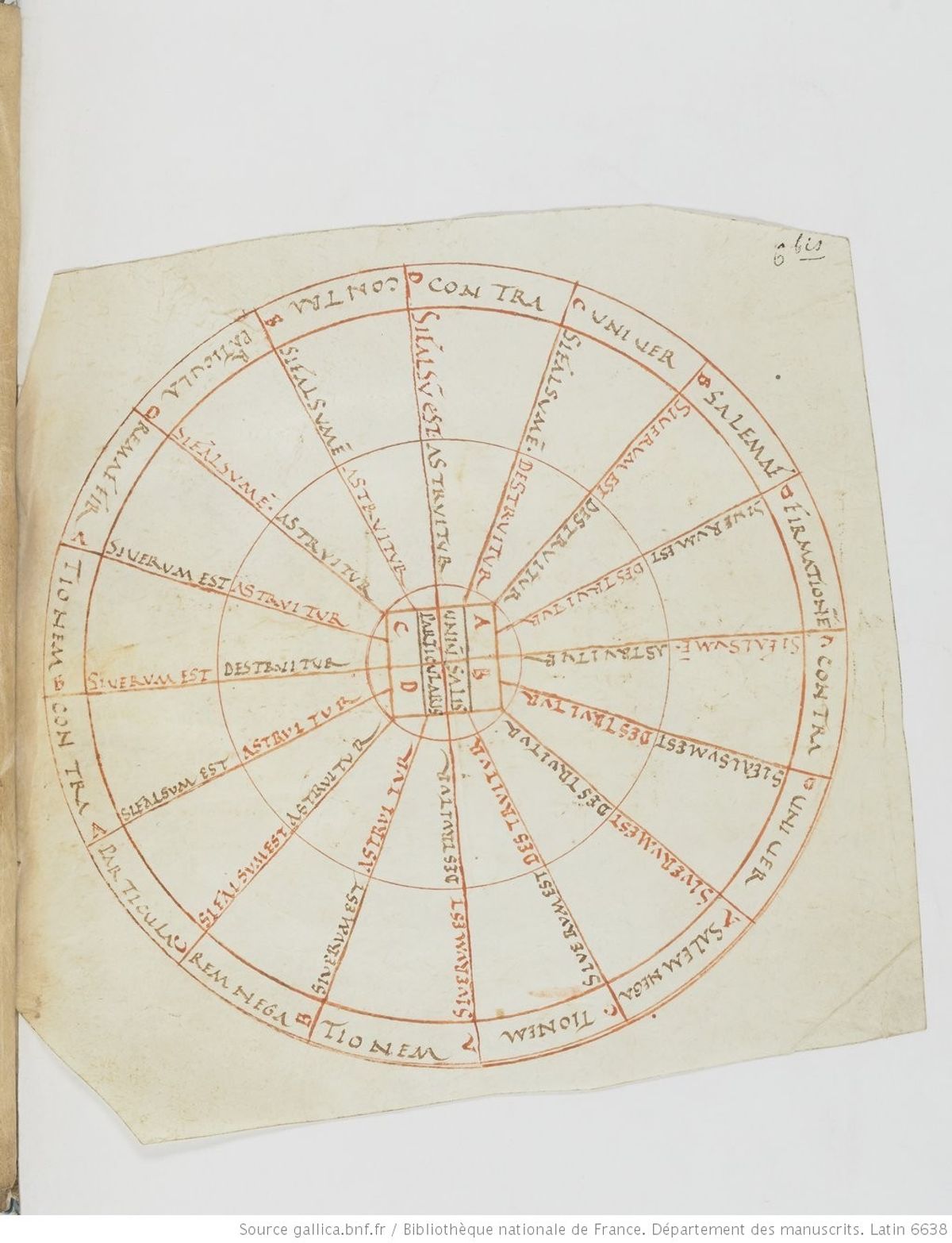

This manuscript contains a ‘wheel of syllogisms’, an alternate means for representing the relationship between propositions to the ’square of opposition’. The wheel is found at the conclusion of a copy of Apuleius’s (c. 123 – 170) exposition on Aristotle’s Peri hermenias and represents a portion of Apuleius’s text: ‘It is clear that someone who has proposed something asserts to it. But either universal is destroyed in three ways: when its particular is shown to be false or when either of the two others – its contrary or contradictory is shown to be true. However it is established in one way: if its contradictory is shown to be false. On the other hand a particular proposition is destroyed in one way: if its contradictory is shown to be true. However it is established in three ways: if its universal is true or if either of the two others – its subcontrary or contradictory is false’.2 In the wheel ‘A’ represents the ‘universal affirmative’, ‘B’ the ‘universal negative’, ‘C’ the ‘particular affirmative’ and ‘D’ the ‘particular negative’.

Each quadrant represents how to deal with one type of proposition: this section, indicated in yellow, deals with the ‘universal affirmative’ (indicated as ‘A’ in the central, red, square of the circle). The text in the outer ring of the circle reads “contra universalem affirmationem”, “against the universal affirmative”. The segments of the quadrant offer four possibilities: If D – the particular negative – is false, the universal affirmative is true; if C – the particular affirmative – is false, the universal affirmative is false; if B – the universal negative – is true, the universal affirmative is false; if D – the particular negative – is true, the universal affirmative is false.

http://hdl.handle.net/1887.1/item:1687093

This wheel diagram shows that scholars experimented with different ways to represent relationships between propositions aside from the ‘square of opposition’. Leiden, UB, BPL 139B was copied at Fleury (the next codicological unit contains some of the logical works of Abbo of Fleury). Abbo also used schemes in his works.

A clue to how the wheel was used can be found in another copy of it, now in Paris: manuscript Paris, BnF, lat. 6638 contains a fragment of De syllogismis hypotheticis of Abbo of Fleury (ff. 1va-4rb), followed by Apuleius’s work. Here the scheme is added on a small piece of parchment now bound into the manuscript. Unlike the copy in Leiden, UB, BPL 139B, this wheel, on what was originally a loose leaf, could have been rotated, allowing the reader to follow the propositions around the wheel more easily. The fact that it was copied on a small sheet suggests that this might have been a study aid, to have to hand while reading Apuleius’s text.

https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b10548529s

Playing with syllogisms III: Leiden UB, VLF 48

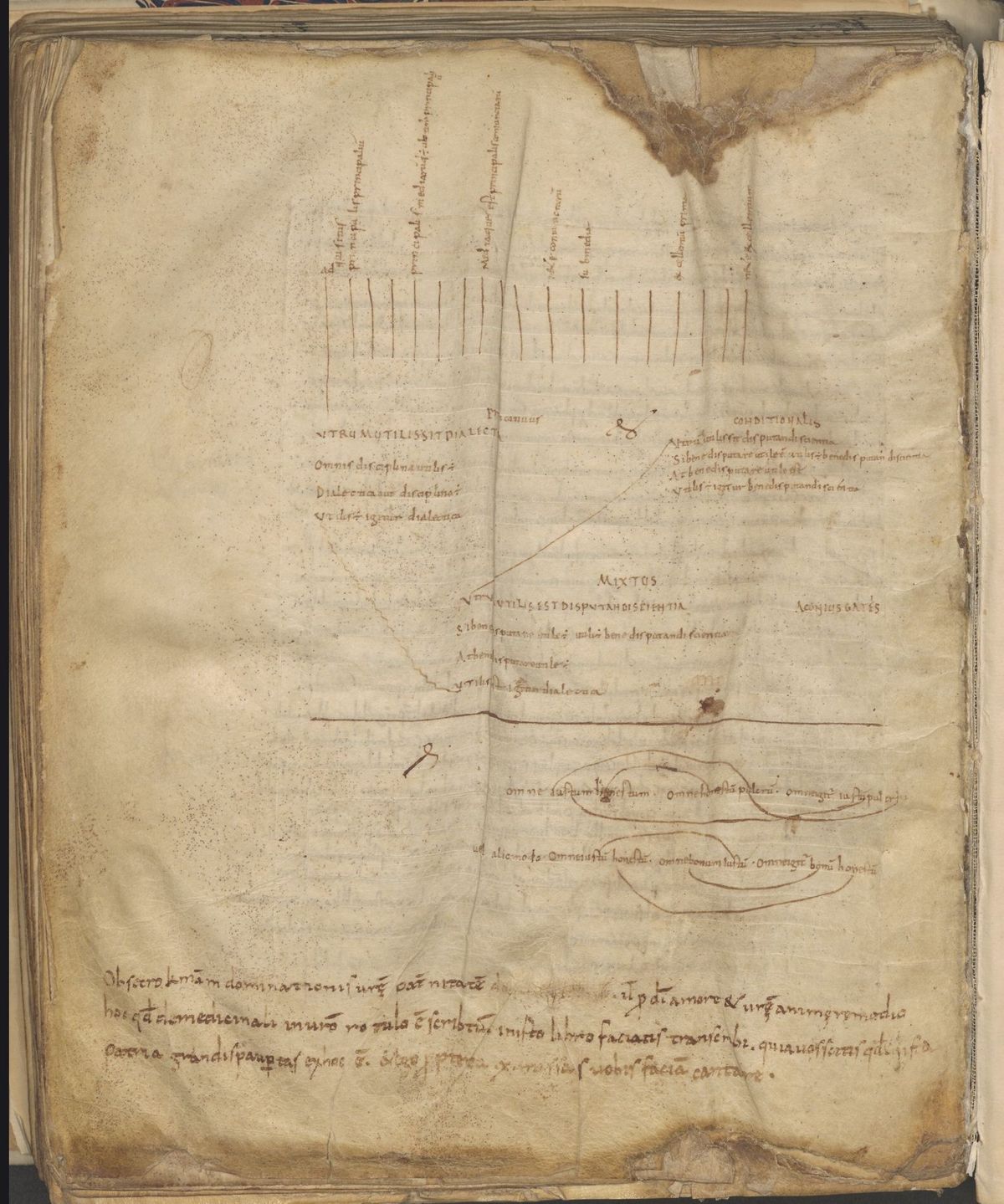

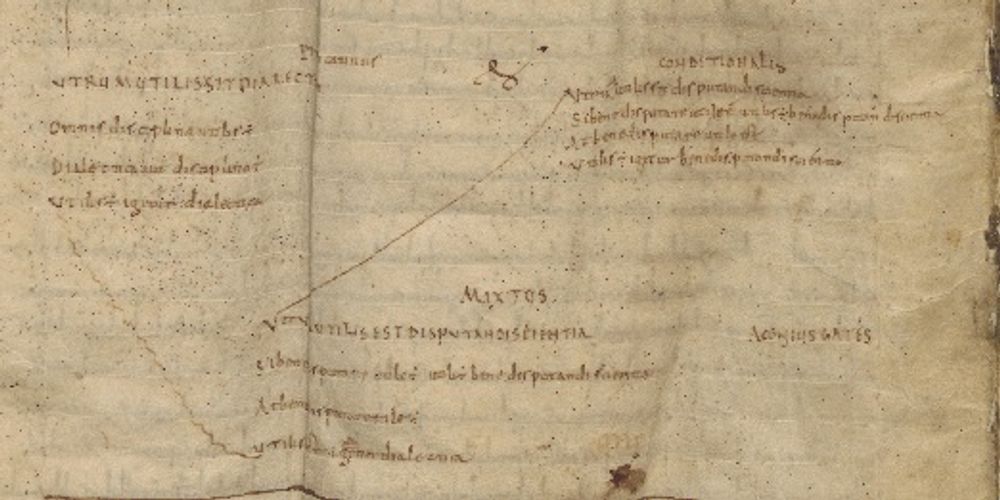

In manuscript Leiden, UB, VLF 48 two scribes have used the blank space at the end of this manuscript of Martianus Capella’s De nuptiis Philologiae et Mercurii as a space for writing some notes: this shows how ‘unused’ parchment could become a venue in which material only tangentially related to the content of the codex was gathered. We know who one of these scribes was – Rather of Verona (890-974) added a copy of a letter at the base of the page. The other scribe added a note on musical pitches and two sets of schemes, separated by a line, regarding syllogistic propositions.

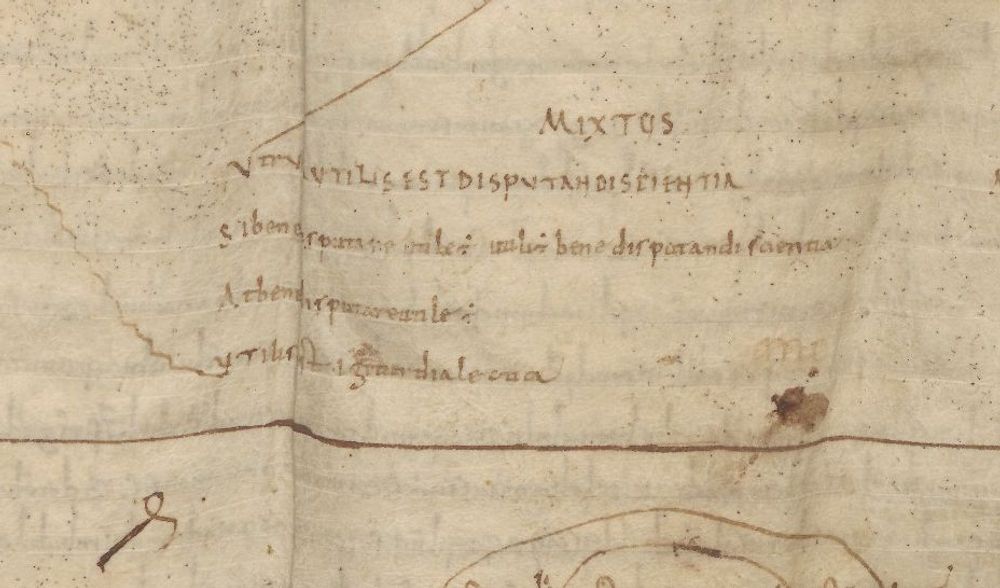

The first scheme uses syllogisms to ‘prove’ the utility of dialectic. Here dialectical methods are harnessed to show that the art itself has merit, but the ‘proof’ also provides an example of dialectical argumentation in action. For example, the scheme includes a so-called ‘mixed’ syllogism: “Whether the knowledge of discussing is useful: If good discussion is useful, the science of discussing well is useful. But good discussion is useful... Therefore dialectic is useful.”

http://hdl.handle.net/1887.1/item:1618282

The inspiration for the text of this scheme is Martianus himself. In De nuptiis, IV.422, the figure of Dialectica offers the same example of a mixed syllogism to prove that dialectic is advantageous. Effectively the reader is working out the steps made by Dialectica in reaching this conclusion; we get an insight into their thought process!

http://hdl.handle.net/1887.1/item:1618282

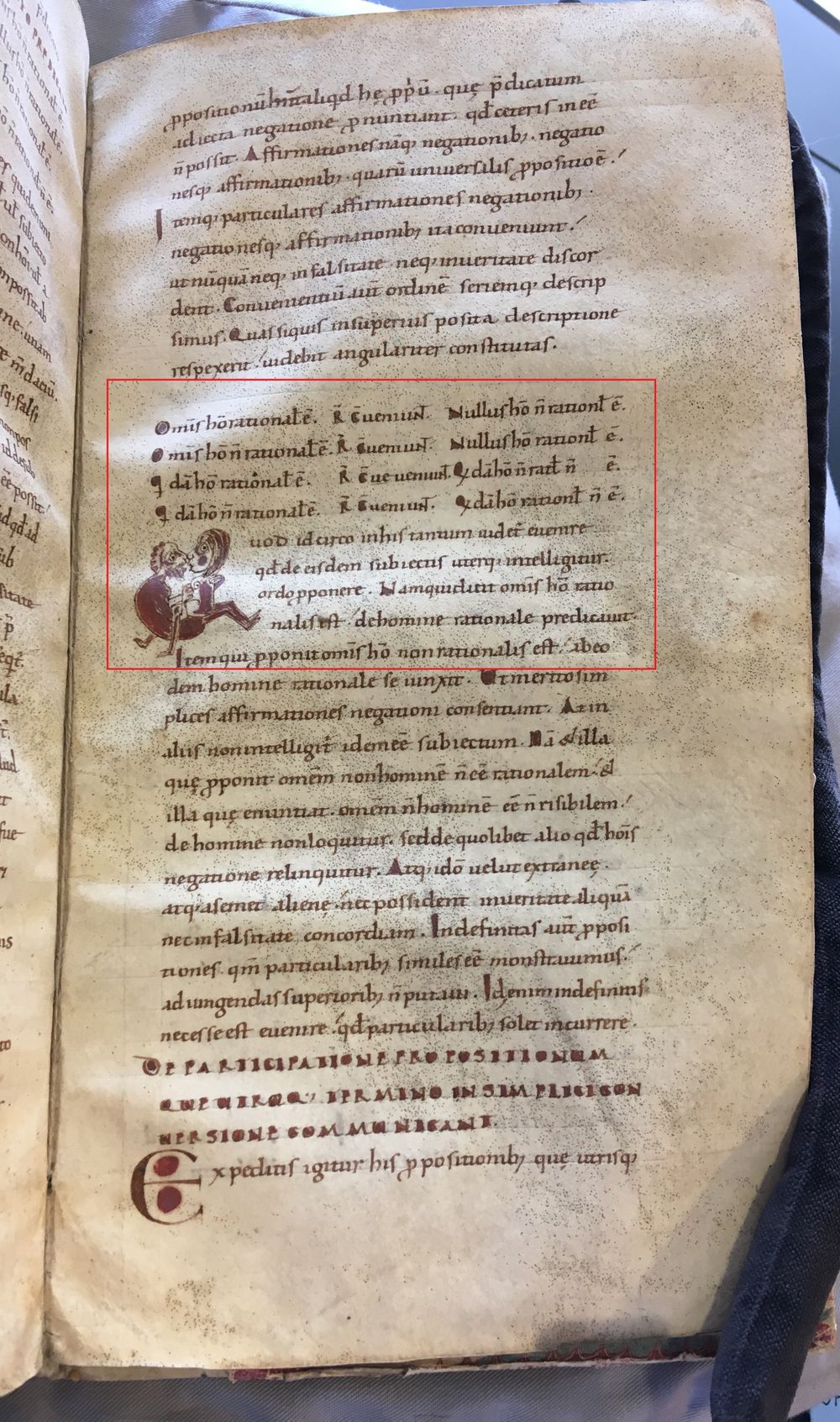

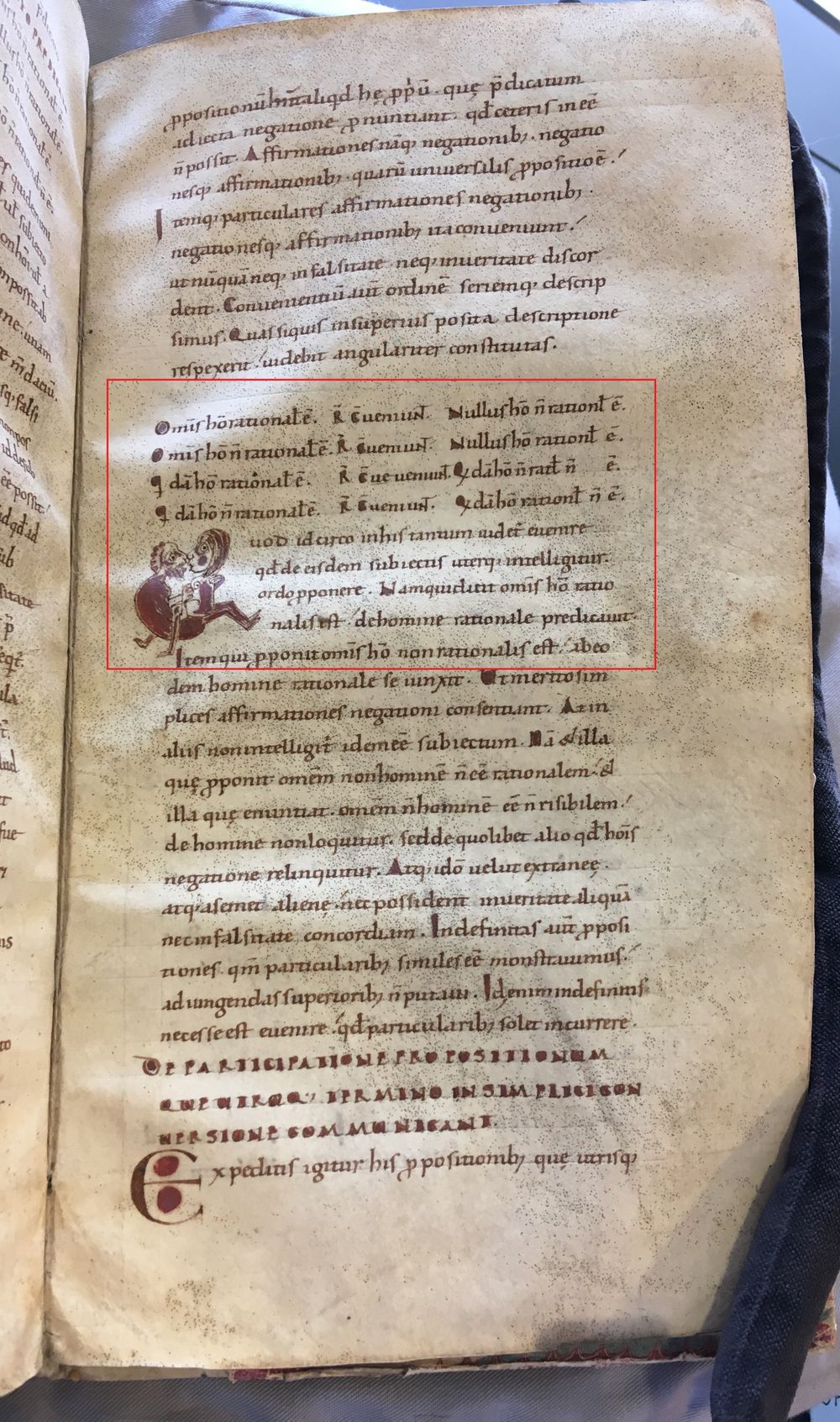

Playing with syllogisms IV: Leiden UB, BPL 84

This segment of text from Boethius’s Introductio ad syllogismos categoricos, an introduction to Aristotle’s theory of syllogisms, gives an example of how one ‘converts’ a proposition. The first line indicates that the proposition ‘Every man is rational’ converts to ‘No man is not-rational.’ This is an example of ‘conversion by obversion’ (if every A is B, then no A is ‘non-B’). Conversion was a useful technique for the medieval logician as it allowed new propositions to be generated from existing ones.

http://hdl.handle.net/1887.1/item:2348775

Although this is quite a technical discussion, the scribe has still found an opportunity to make his reader laugh, making the initial ‘Q’ out of a man and woman making love. Her blush and guilty look at the reader gives the impression that the couple have been caught in the act!

http://hdl.handle.net/1887.1/item:2348775

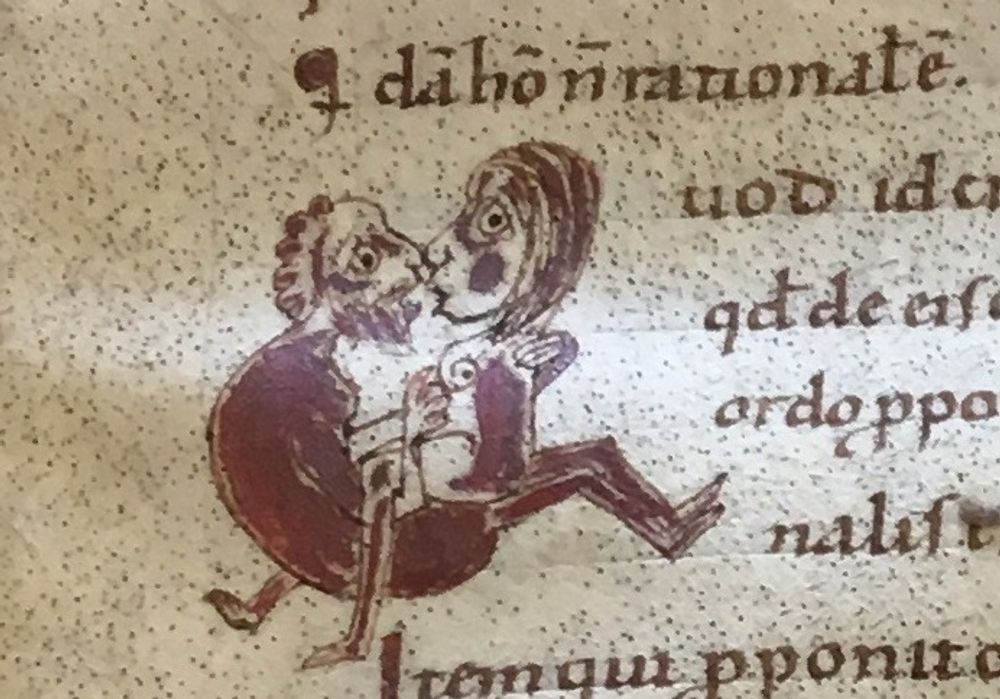

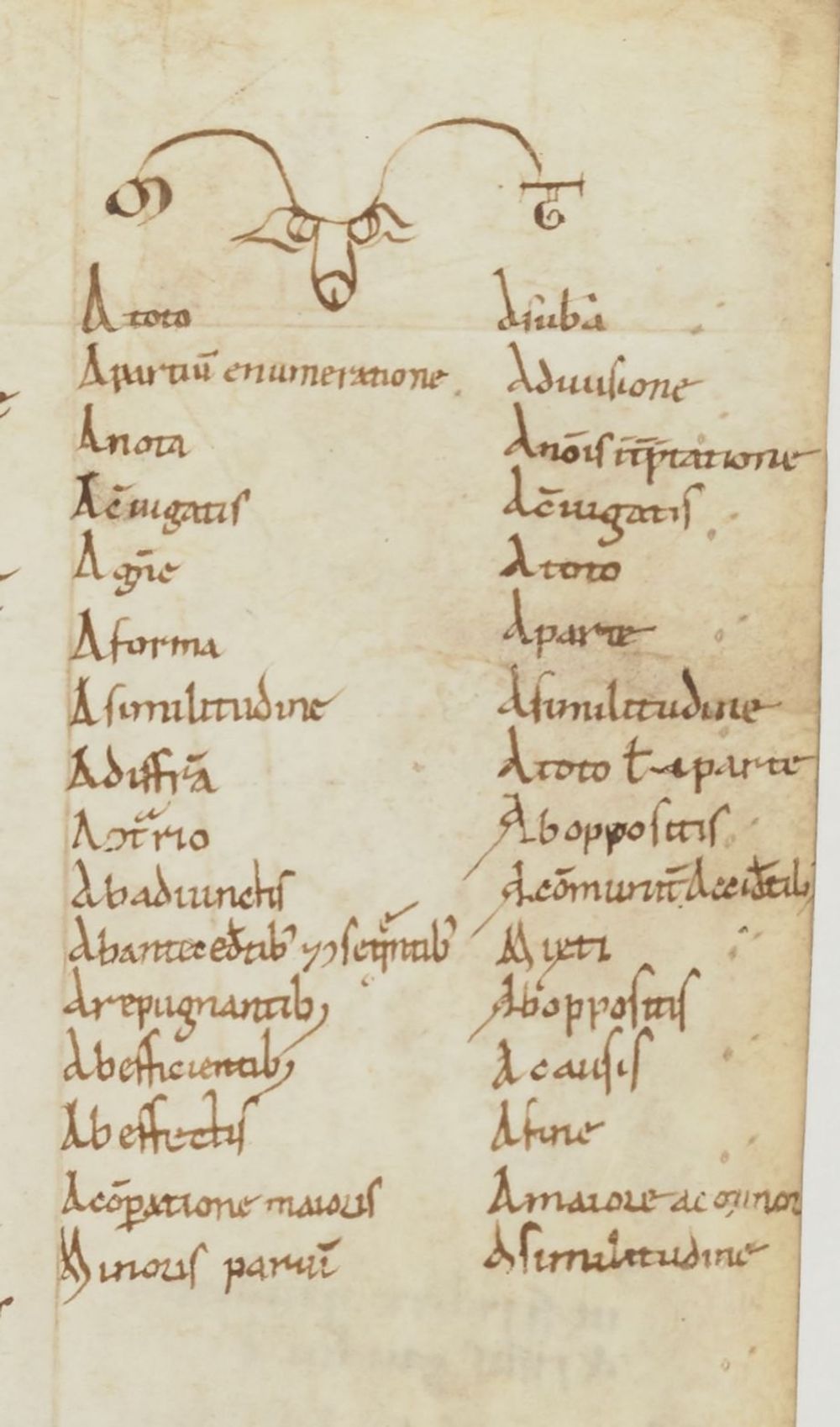

Perhaps the reader would have also got a laugh out of this list of commonplaces used for argumentation (‘loci’) found in another collection of Boethian logical works. Here the list is decorated with a flourish that on closer inspection is clearly male genitals! These sexual details have not been defaced or erased, suggesting that the (most likely religious) reader of the texts was not without a sense of humour.

https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b525072333

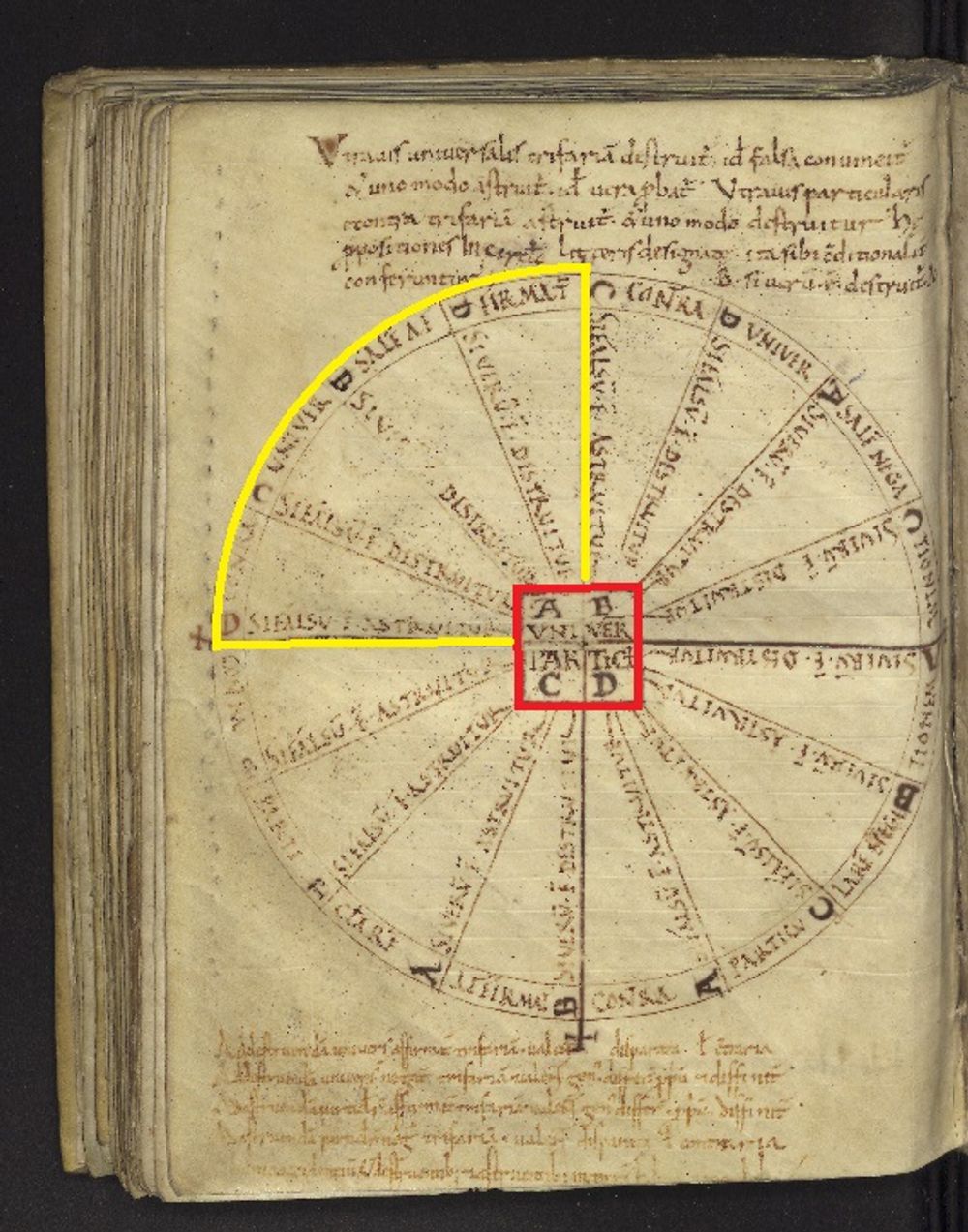

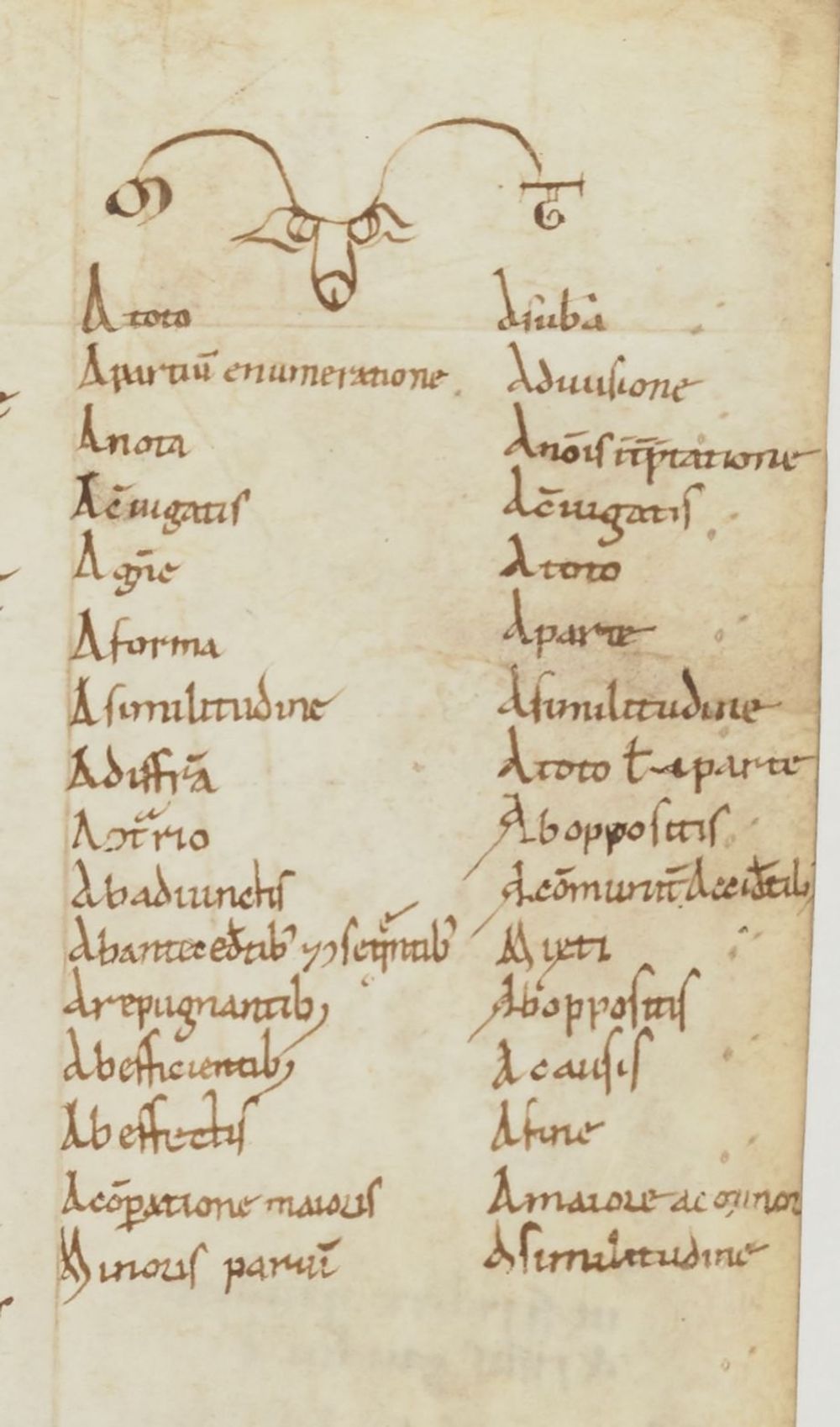

An elaborate scheme has been added at the end of the copy of the Introductio ad syllogismos categoricos found in manuscript Leiden, UB, BPL 84, offering a summary of the characteristics of ‘simple propositions’. The scheme combines two parts of Boethius’s text; first his explanation of simple propositions (PL, 64, 769C-769D) and then some of the examples he gives later in the text of how such propositions convert. The scheme begins with two examples of simple propositions which do not ‘convert’, namely, “Plato is a philosopher” and “Virtue is good”. These syllogisms cannot be converted by simply swopping the subject and predicate terms. ‘A philosopher’ is not necessarily Plato! Similarly, virtue is not the only ‘good’.

http://hdl.handle.net/1887.1/item:2348775

Sources used for this contribution:

- Gersh, S., Concord in discourse: Harmonics and semiotics in late classical and early medieval Platonism (Berlin, Mouton de Gruyter, 1996)

- Migne, J.-P. (ed.), Patrologia Latina, vol. 64

- Parsons, T., Articulating Medieval Logic (Oxford, Oxford University Press, 2014)

- Londy, D. and Johanson, C., Philosophia antiqua: The logic of Apuleius (Leiden, Brill, 1987)

- Rouse, R. H., ‘Manuscripts belonging to Richard de Fournival’, Revue d'histoire des textes, 3 (1974), 253-269

- Stahl, W. H. Martianus Capella and the seven liberal arts. Vol II: The marriage of Philology and Mercury (New York, Columbia University Press, 1971)

-

Contribution by Irene O’Daly.

Cite as, Irene O’Daly, “Reasoning through syllogisms”, The art of reasoning in medieval manuscripts (Dec 2020), https://art-of-reasoning.huygens.knaw.nl/syllogism. ↑ -

Translation from S. Gersh, Concord in Discourse. Harmonics and semiotics in late classical and early medieval Platonism (1996), pp. 168-9 ↑

Next Read:

Next Read: