A controversial art?

Images of dialectic through the ages1

In Antiquity, dialectic was associated with truth-finding and discernment. It was seen as a tool that helped distinguish between true and false, between valid and invalid assertions. Among early Christians, however, dialectical disputations came to be seen as a source of controversy and strife. Distrust of dialectic lived on in the early middle ages. With the rise of scholasticism in the late eleventh and twelfth centuries, the reputation of dialectic improved considerably. This section of the exhibition presents some verbal and visual images of dialectic, reflecting a development in which dialectic gradually became more socially acceptable and reliable.

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Plato_Aristotle_della_Robbia_OPA_Florence.jpg

Already in Antiquity, dialectic not only invoked positive connotations but was associated with conflict and assault. The philosopher Zeno of Elea (c. 490-430 BC) is reported to have said: ‘Rhetoric is an open hand, dialectic a clenched fist.’2 The latter image invokes the setting of a boxing match and supports the notion that those who enter in a dialectical disputation do not set out for a friendly exchange of opinions, but aim to win an argument and take their opponent down to the ground.

Plato’s dialogue Protagoras (c. 380 BC) offers another example of Zeno’s boxing metaphor. A debate between Socrates and the sophist Protagoras is depicted as a boxing match, complete with ground rules, a referee and a cheering audience.3 Socrates out-performs Protagoras and manages to defeat his sophistry, but not before receiving some heavy blows himself. After being ‘hit’ by a particularly effective argument of his opponent, Socrates is reported to have said: “Many of the audience cheered and applauded this. And I felt at first giddy and faint, as if I had received a blow from the hand of an expert boxer”4

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Boxing_scene_Louvre_G384.jpg

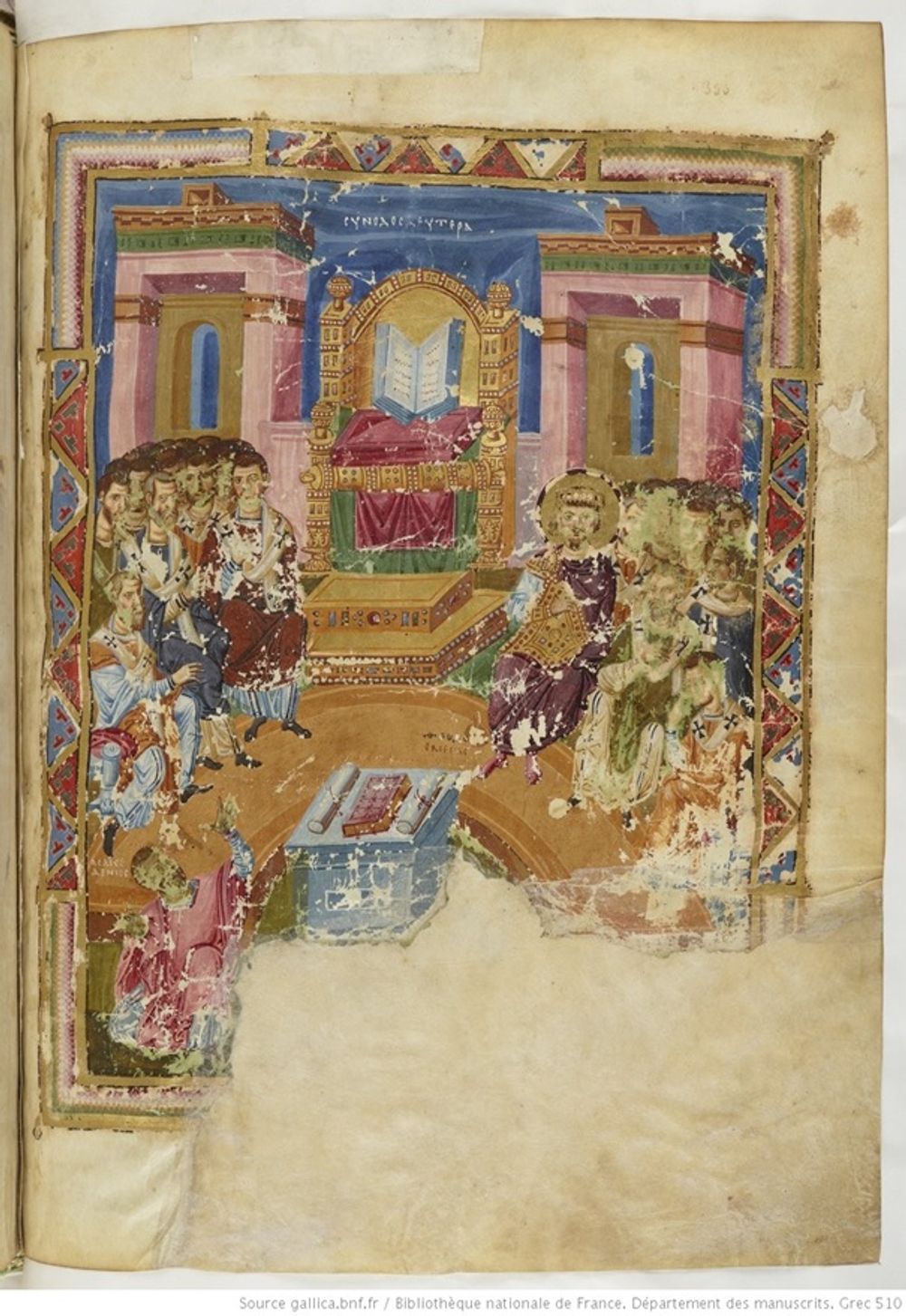

Christians regarded the art of dialectical argumentation increasingly with distrust. Heated disputations had disrupted the synods of the early church, with the result that dialectical argumentation itself came to be considered a threat to the unity and stability of Christian communities. The Christian author Tertullian (d. 220) blamed Aristotle for introducing this ‘root of contention’: “Wretched Aristotle!”, he wrote, “who invented dialectic for these men, the art which destroys as much as it builds.”5 Here you see a miniature representing the second ecumenical council, held in Constantinople in 381. This council was rife with conflict, according to church histories, but the miniaturist has depicted an orderly gathering, in which a gospel book holds central stage.

https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b84522082

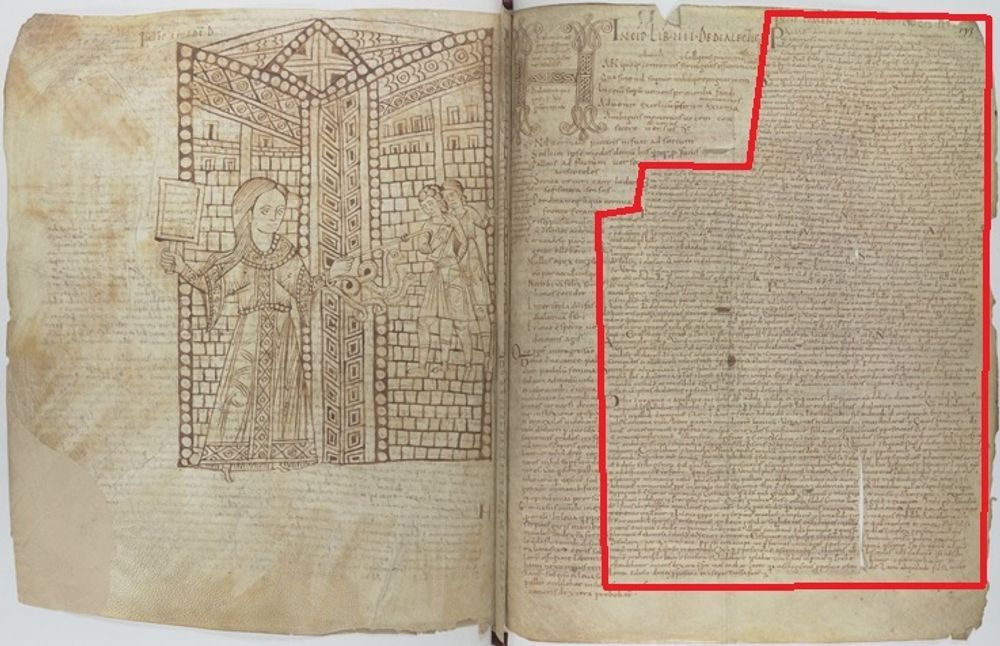

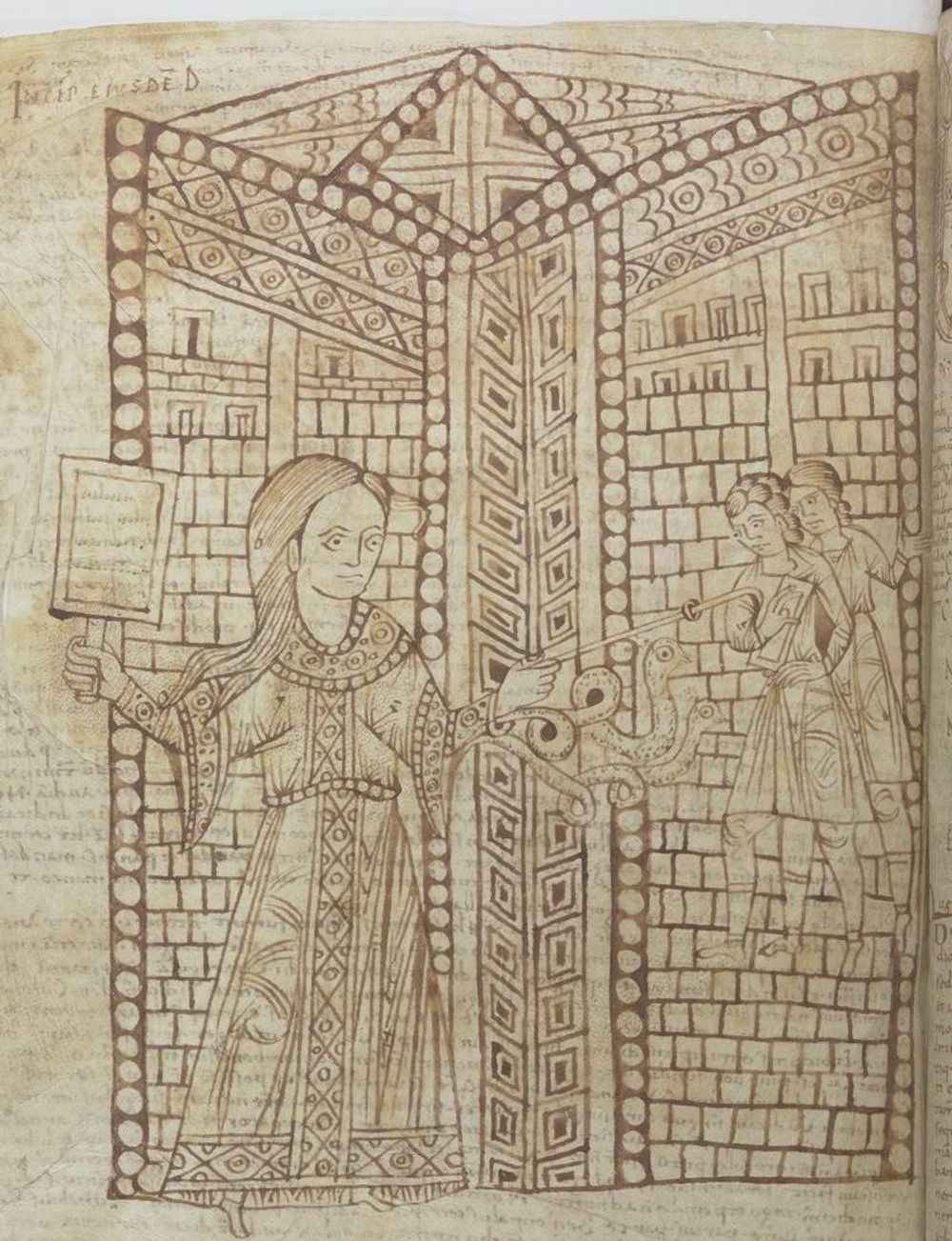

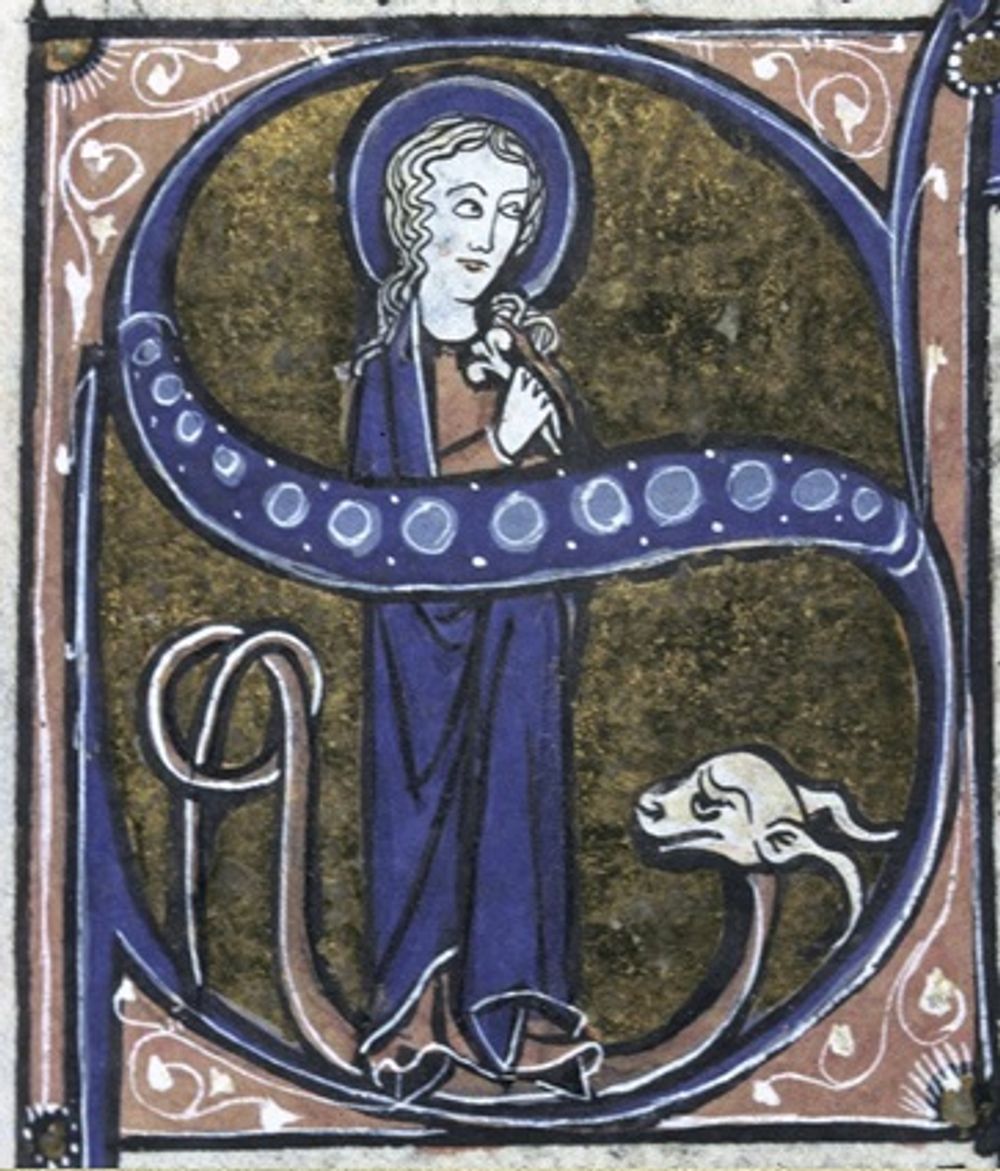

Female personifications of dialectic and the other liberal arts were depicted throughout the middle ages. One of the oldest descriptions of Lady Dialectic, portraying her as a clever but untrustworthy woman, can be found in Martianus Capella’s encyclopaedia of the liberal arts, dated to the early fifth century. The oldest surviving illustrated copy of Martianus’ encyclopedia of the liberal arts is manuscript Paris, BnF, lat. 7900A, which dates to the tenth century. The illustrator depicted Lady Dialectic on the verso opposite the opening page of Martianus’ chapter on dialectic. In the ninth century, scholars John Scottus and Remigius of Auxerre wrote comments on Martianus’ chapter on dialectic. It is worth looking into Martianus’ description of Lady Dialectic, penned in the fifth century, and compare it to the comments that this description invited in the ninth century, and to the way it was illustrated in the tenth century. The description, comments and illustration of Lady Dialectic’s appearance, attire and attitude reveal how the benefits and risks of dialectical argumentation were assessed in different periods.

https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b10546779x

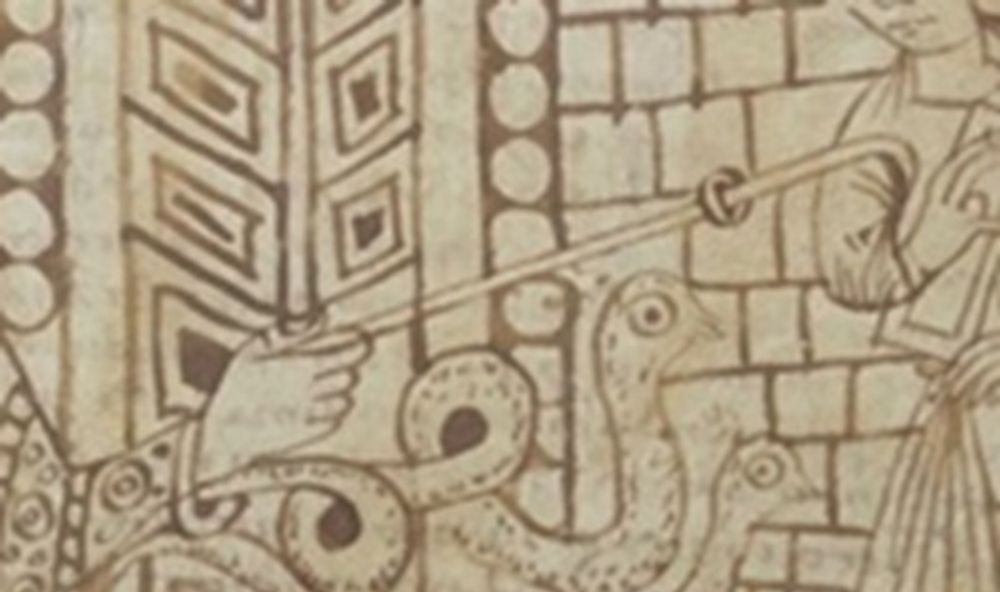

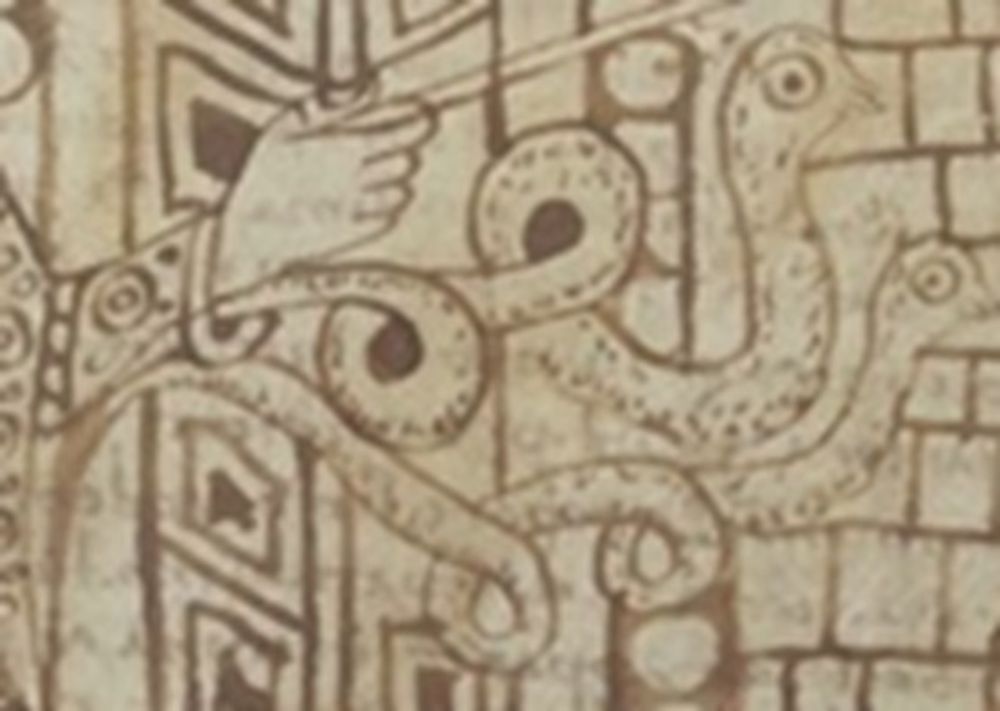

In his narrative on the liberal arts, Martianus recounted how Lady Dialectic entered the assembly of the gods. He described her pale complexion, piercing eyes and beautiful, intricately tied up curls. In her left hand she held a snake, in her right hand a wax tablet with attractive premises, held on the inside by a hidden hook. “Then, if anyone took one of those premises”, Martianus wrote, “he was soon caught and dragged toward the poisonous coils of the hidden snake, which presently emerged and after first biting the man relentlessly with the venomous points of its sharp teeth, then gripped him in his many coils and compelled him to the intended position.”6

https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b10546779x

Martianus said about Dialectic’s hairstyle that “her intricate coiffure seemed beautifully curled and bound together, and descending by successive stages, it encompassed the shape of her whole head”. The Latin clause “deducti per quosdam consequentes gradus” (“descending by successive stages”) is a reference to the successive steps of logical argumentation.7

John Scottus’s interpretation of Dialectic’s tangled hairdo is rather negative: “Her premises for discussion are intricate, deceitful and seductive”8 Remigius of Auxerre’s comment is similar to John’s: “Intricate and interwoven hair stands for deceitful and seductive premises.9

https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b10546779x

Martianus wrote: “a set of patterns carefully inscribed on wax tablets […] was held on the inside by a hidden hook”.

Remigius of Auxerre commented: “The patterns indicate a simple premise for discussion. The hook however stands for an ensnaring conclusion.”

https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b10546779x

Martianus described how Dialectic held a serpent in her left hand, hidden under her cloak. John Scottus interpreted Dialectic’s serpent as a representation of sophistic arguments: “The serpent stands for the subtleties of sophisms”10

Sophistic argumentation stood for the dark side of dialectic. From a positive perspective, dialectic was a critical tool to distinguish true from false. Sophisms, to wit clever but false arguments used deliberately to deceive, were the object of distrust.

https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b10546779x

Let us look again at the illustration in full size. At first sight, the tenth-century illustrator followed Martianus’ description closely. We see Lady Dialectic holding a wax tablet with a handle. The lines written on it are illegible, but it is easy to imagine that these are the attractive premises for discussion to draw people near. The illustrator evidently has set the scene in a school context rather than in a mythical assembly of gods or in a fighting arena. The two young men are not depicted as formidable opponents, but as timid students. One of them is clenching a book. The wax tablet that Dialectic holds up for them to see underlines the school setting. The image underscores that by the tenth century dialectic has entered the curriculum of monastic schools, although it was perhaps only studied by advanced students and scholars. The school setting does little to domesticate Dialectic’s intimidating character. Snakes still come out of her sleeve and she grabs the arm of one of the students with her hook.

https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b10546779x

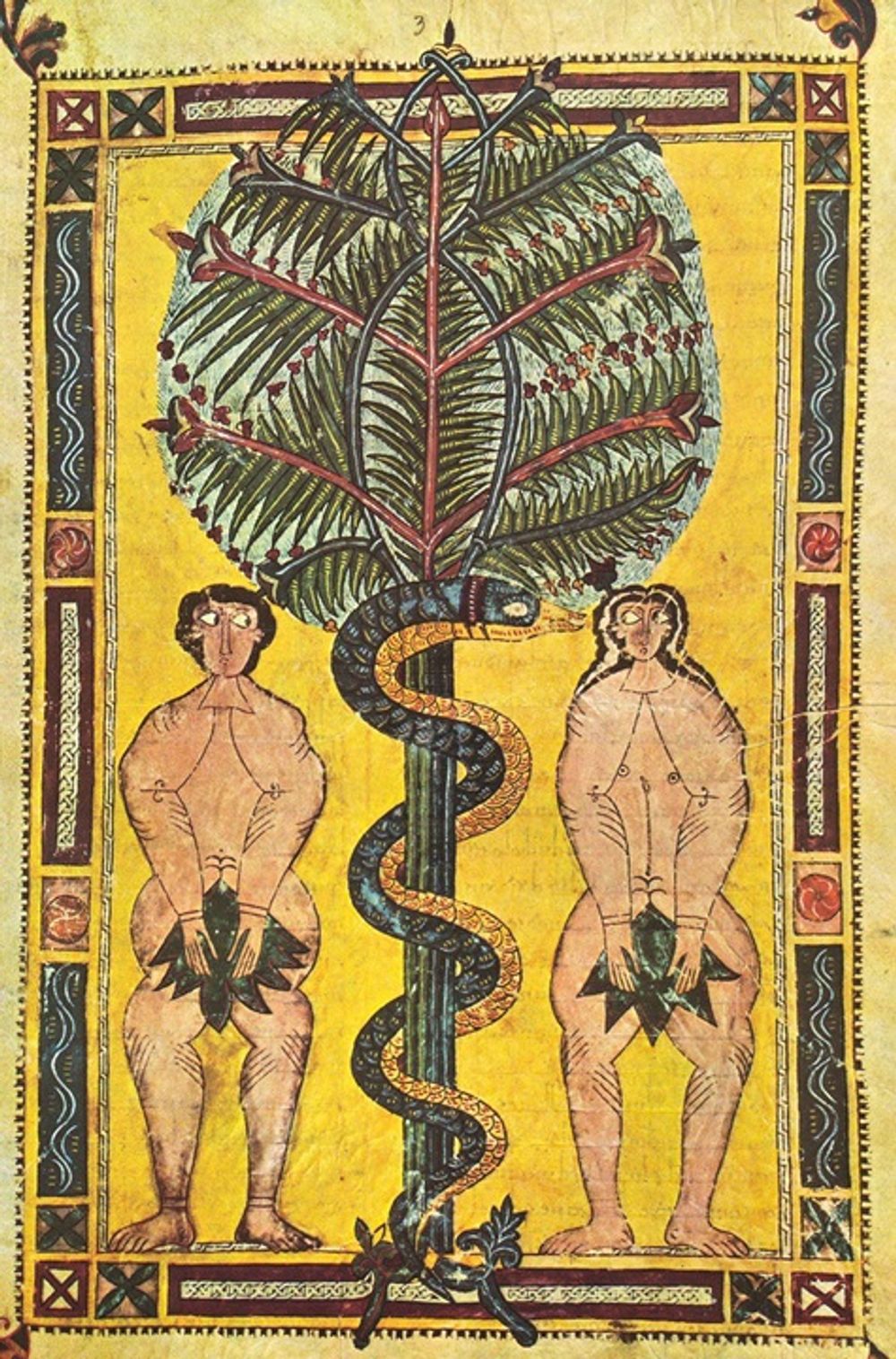

Martianus was a pagan author. The serpent he put in Lady Dialectic’s hand had little, if anything, to do with Christian symbolism. In Christian discourse, Dialectic’s pet animal was associated with the treacherous charms of the devil-serpent in the Book of Genesis, who persuaded Eve to eat from the tree of knowledge, so she would be like God and know the distinction between good and evil (Gen. 3, 4). In a way, Dialectic’s promise is similar to that of the Old Testament serpent: with her help and instructions one learns to distinguish between true and false.

The treacherous nature of Dialectic’s serpent came to be associated with the venom of heresy. Heretics were considered to be experts in dialectical disputations and false and misleading reasoning.11

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:B_Escorial_18.jpg

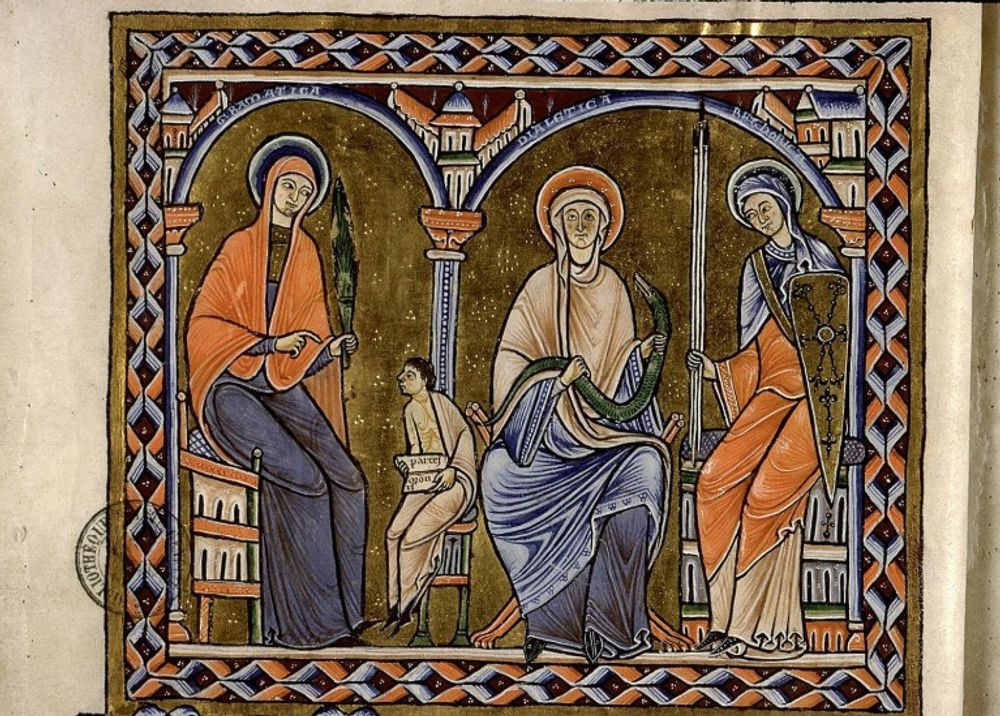

The serpent became a regular feature of depictions, verbal or visual, of the female personification of dialectic. This miniature in a twelfth-century manuscript, Paris, Bibl. Sainte-Geneviève, Ms. 1041, depicts the arts of the Trivium. Lady Dialectic is seated in the middle, holding the serpent in her lap. On her right-hand side (left to the viewer) sits Lady Grammar and on her left-hand side Lady Rhetoric. Rhetoric holds a shield and Grammar a rod. The student sitting in front of Lady Grammar looks just as intimidated as the students in manuscript Paris, BnF, lat. 7900A.

http://initiale.irht.cnrs.fr/decor/72821

From the twelfth century onwards, stone carvings of Lady Dialectic and her sisters from the liberal arts can be found in portals of cathedrals, for example in Laon, Auxerre and in Chartres. Their location attests to the increased prominence of the artes, which are now being regarded as resources of knowledge of God and his creation. Gothic architecture is often directly associated with the program of scholasticism, which seeks to harmonize Christian theology with Aristotelian methods of logical argument and debate.12

https://albertblackwell.blogspot.com/2013/09/chartres-cathedral-and-seven-liberal.html

https://albertblackwell.blogspot.com/2013/09/chartres-cathedral-and-seven-liberal.html

https://albertblackwell.blogspot.com/2013/09/chartres-cathedral-and-seven-liberal.html

https://albertblackwell.blogspot.com/2013/09/chartres-cathedral-and-seven-liberal.html

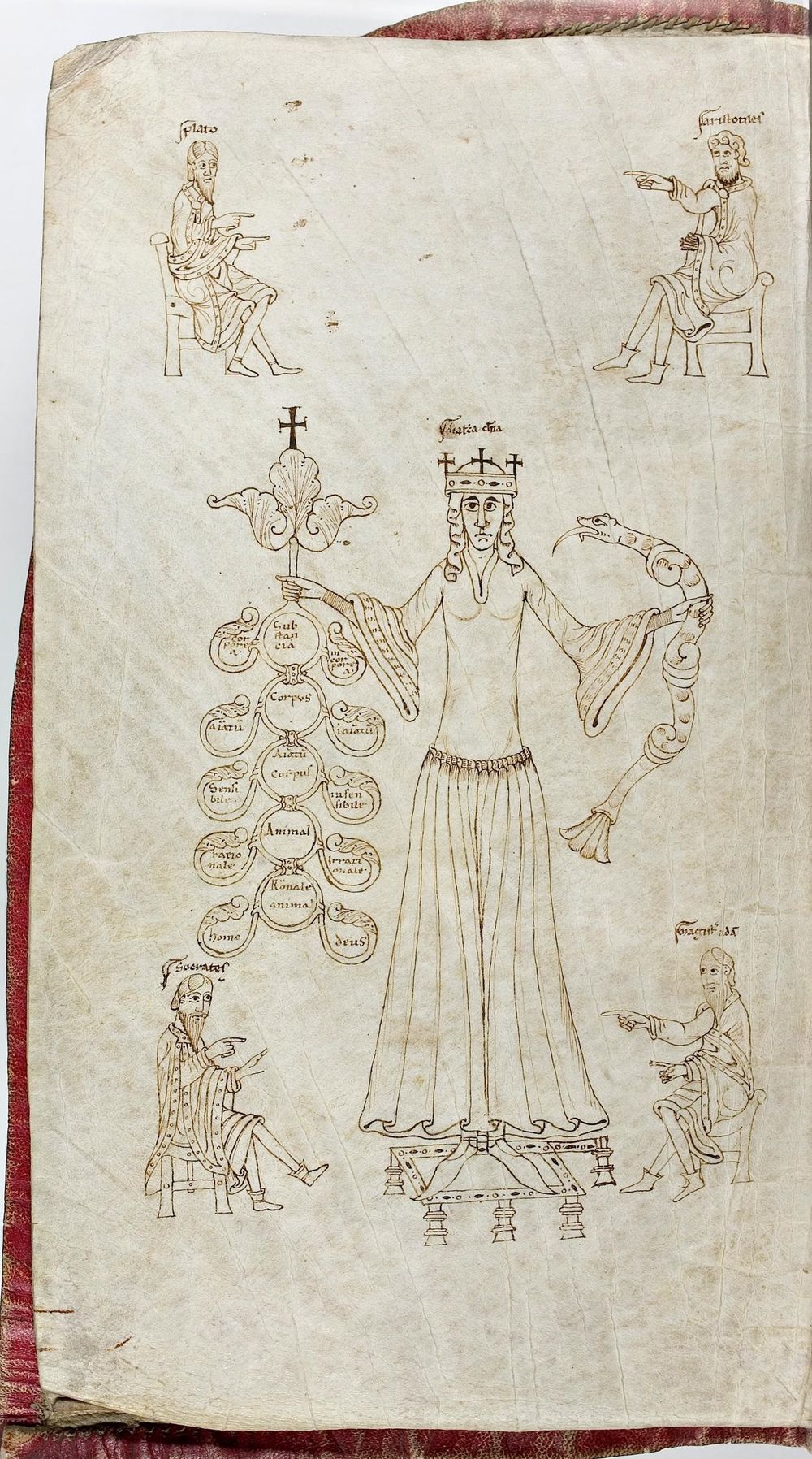

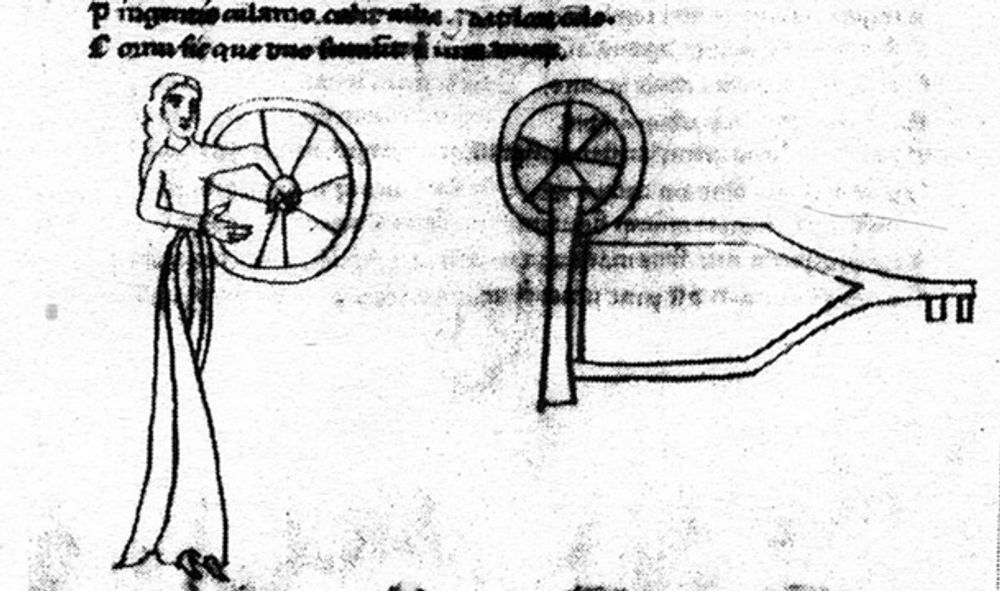

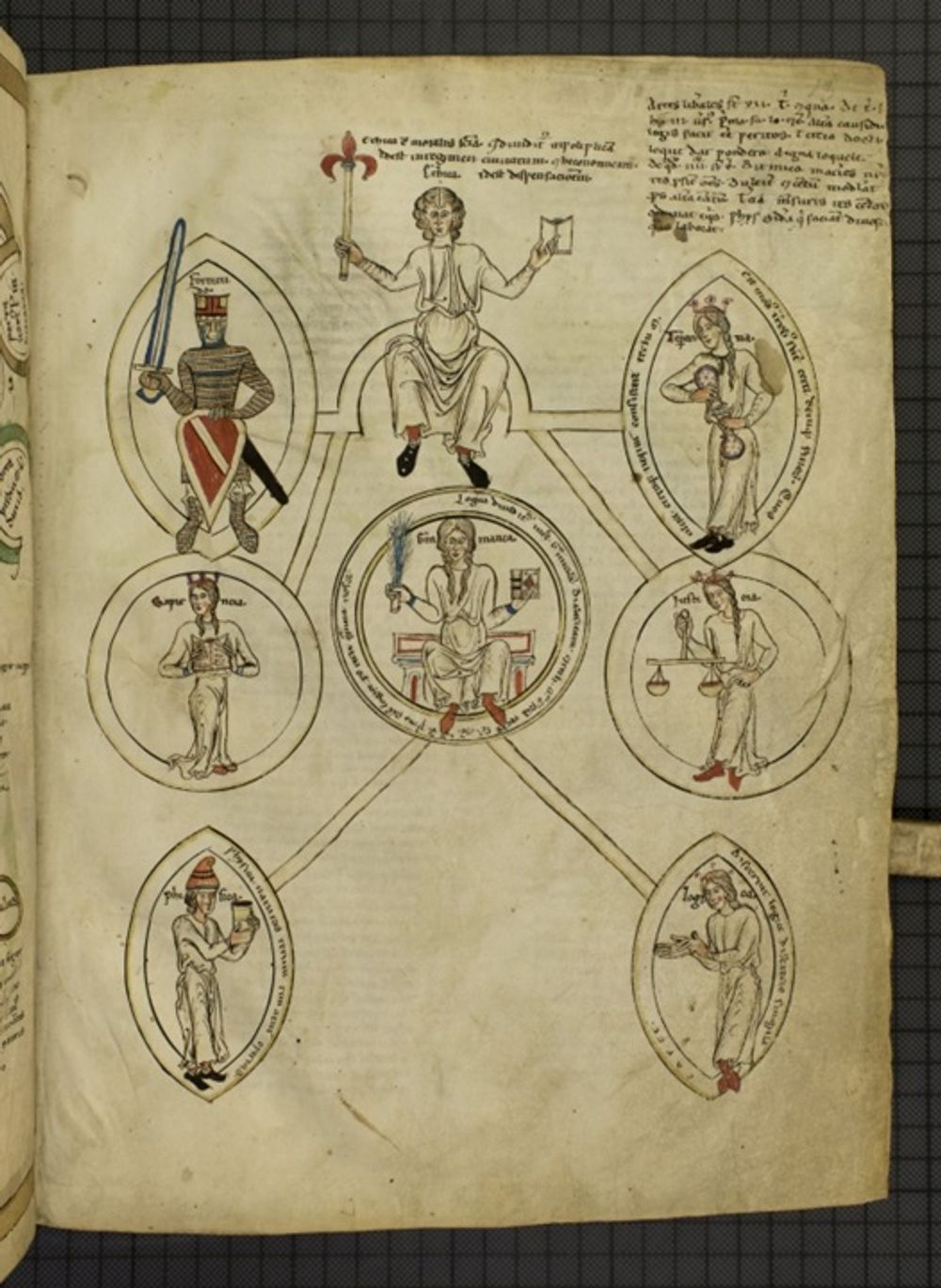

In this manuscript of logical texts, Darmstadt, Universität- und Landesbibliothek, Hs. 2282 dated to c. 1140, we see that Lady Dialectic’s status is definitely improving. She stands on a footstool and is wearing a crown. Above her head is written ‘dialectica domina’. Her left hand still holds the serpent, but the beast is no longer hidden under her cloak as a treacherous weapon, but held openly and proudly, as if it were a scepter.13 In her right hand, the tablets with attractive premises, described by Martianus, have been replaced by a Porphyrian tree. This is a significant change of attribute. Instead of seductive premises Dialectic now holds a helpful diagrammatic representation of knowledge. This new iconography is probably related to dialectic’s prominent place in the curriculum of the cathedral schools.

http://tudigit.ulb.tu-darmstadt.de/show/Hs-2282

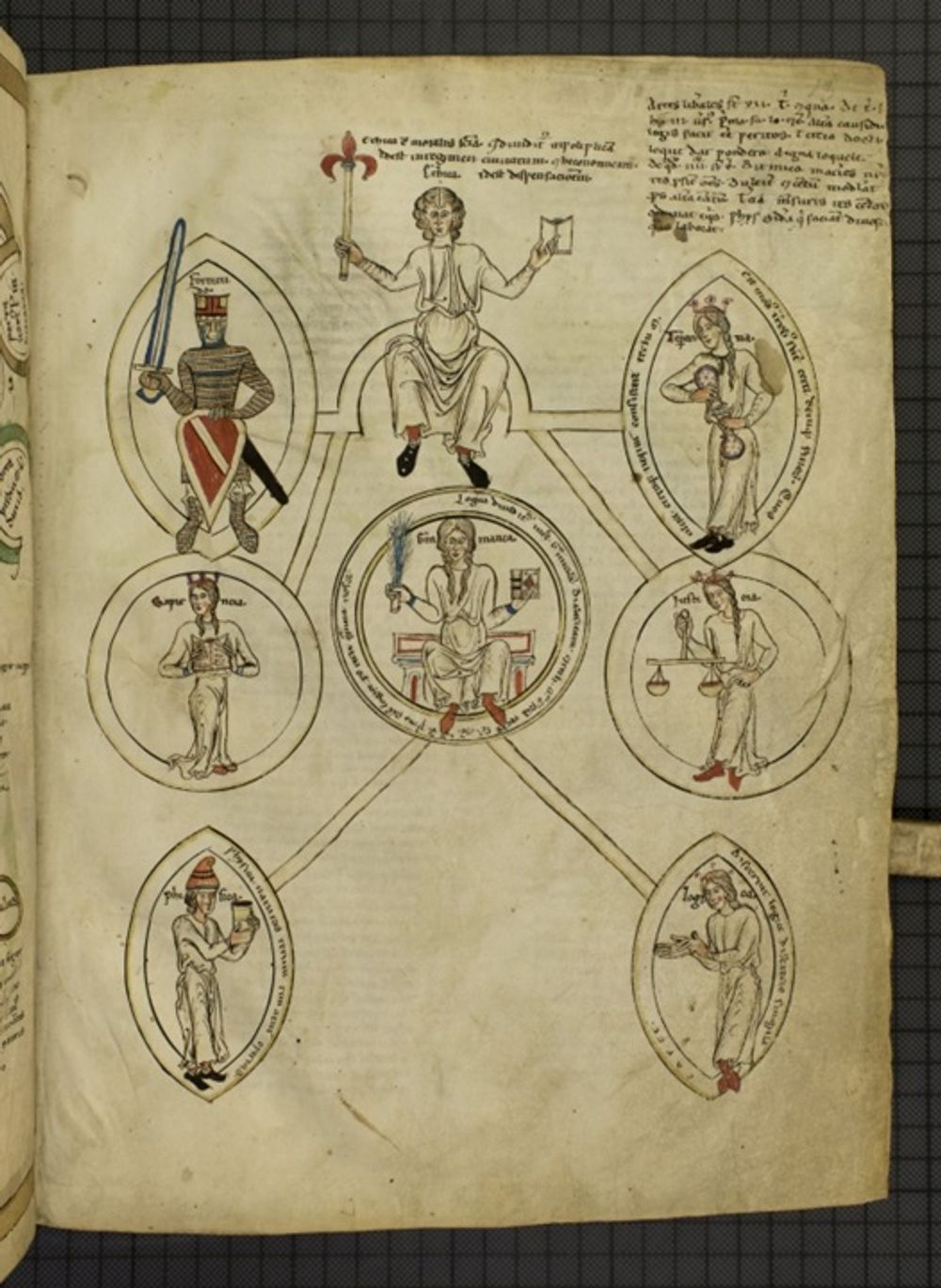

In this illustration dated to c. 1180 Lady Dialectic is dressed in courtly fashion, wearing a hood and a robe. Her right hand is pointing and in her left hand we do not find the traditional serpent but a dog’s head with bared teeth. The inscription in the arch above her head reads: "Argumenta sino concurrere more canino“; “I allow arguments to follow each other (or: engage in battle) in the manner of a dog”. The inscription offers another example of an association between argumentation, battle and (verbal) clashes, here represented by the dog.

https://digi.ub.uni-heidelberg.de/diglit/engelhardt1818bd2/0001/image

The allegorical poem Anticlaudianus (c. 1280) of Alanus de Insulis or Alain de Lille is a testimony to the scholastic program that placed the liberal arts in the service of the study of theology. In the Anticlaudianus, the liberal arts build a cart for Prudentia and take her to God. Reason acts as the charioteer of the team. Only during the last part of the journey to God, Theology takes over from the liberal arts.

https://www.flickr.com/photos/quadralectics/8003072562/in/photostream/

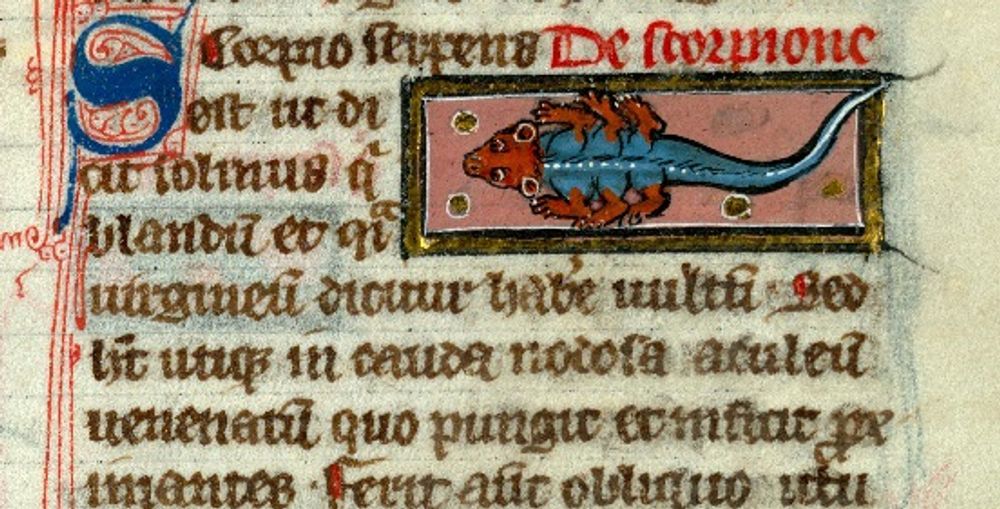

In the high middle ages, dialectic often went by the name of logic. In depictions of the arts, we now encounter Maiden Logic instead of Lady Dialectic. When Alanus described the liberal arts one by one, he provided the maiden Logic with an original set of attributes: Her right hand offers a flower (representing grace and honour), but her left hand holds a scorpion with a sharp, stinging tail. The scorpion was considered to be a type of serpent.

With the attributes of the flower and the scorpion Alanus stressed the different faces of logic (dialectic). Logic can be used for good and for bad. In his words: “the one hand provokes laughter, the other ends with tears, the one captures, the other chases away, the one moves, the other poisons, the one anoints, the other stings”.14 Like Martianus’ Lady Dialectic, Alanus’ Maiden Logic is an untrustworthy woman. Her right hand, her good side, in the end only serves the treacherous intentions of the left hand (manus sinistra) — her ‘sinister’ side.

http://initiale.irht.cnrs.fr/decor/86928

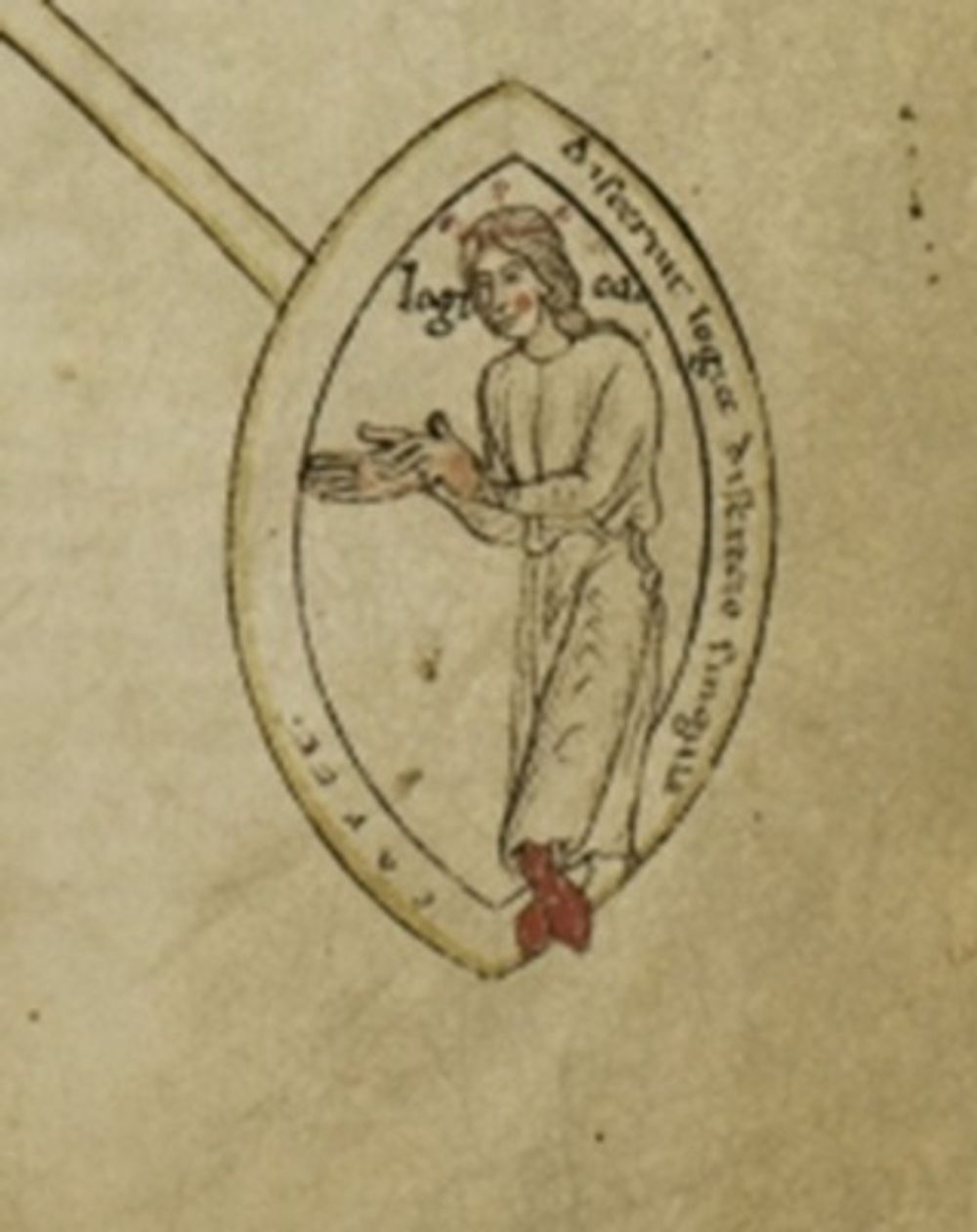

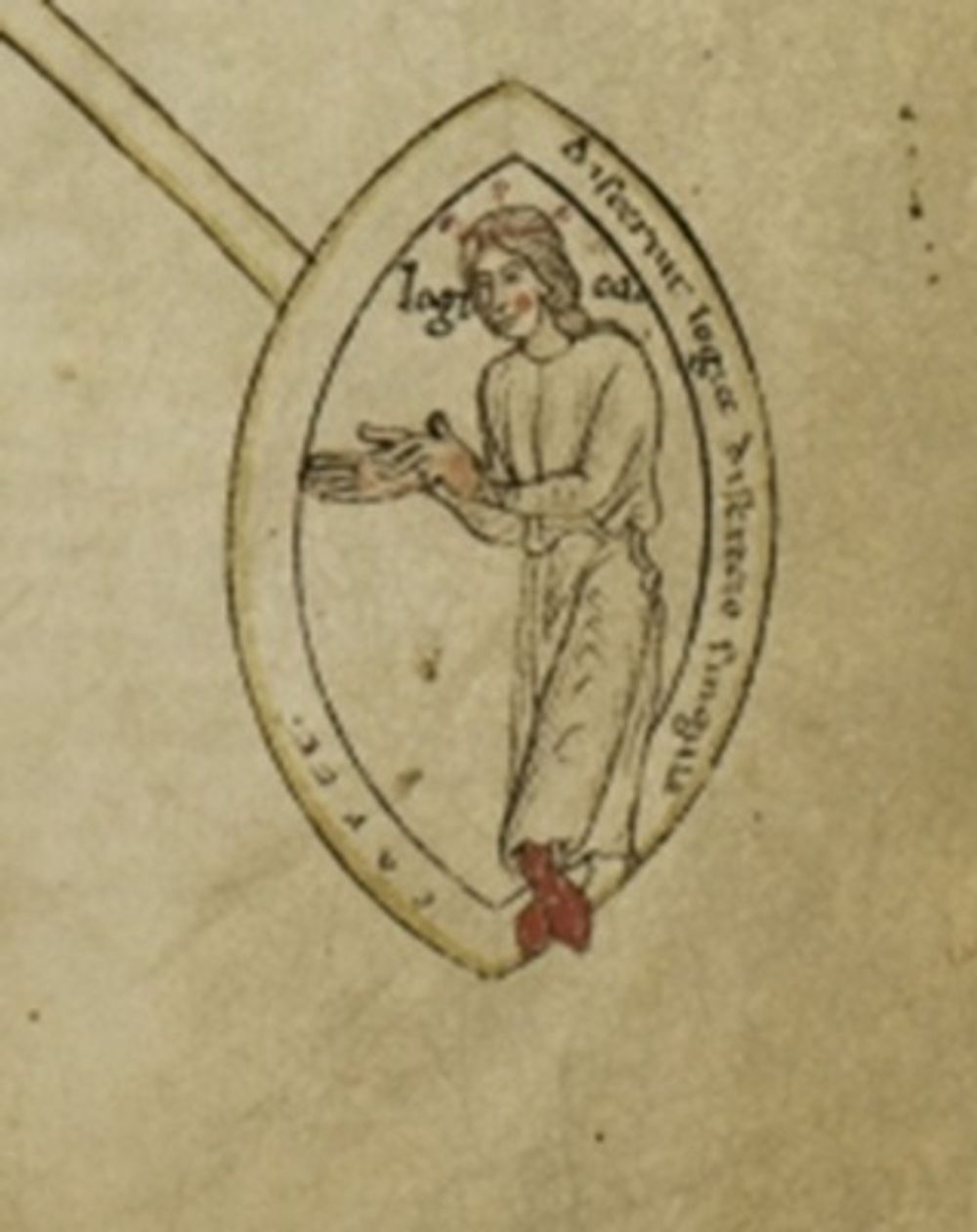

No serpent or scorpion can be detected in the hands of Lady Logic in this thirteenth-century manuscript from the monastery of Admont. In fact, she needs both her hands to make a gesture of argumentation. Lady Logic holds the index and middle finger of her right hand against the flat of her left hand. The position of the fingers signify the propositio and assumptio of syllogistic reasoning. One or two outstretched fingers signal that Lady Logic has reached the end of her argumentation. Here, the attribute of the treacherous serpent has been replaced by a gesture of rational, step by step argumentation.

https://manuscripta.at/?ID=26018

https://manuscripta.at/?ID=26018

Lady Logic is holding her serpent again in this miniature in a manuscript of Heinrich von Mügeln, Der meide Kranz (c. 1355), an allegorical poem on the liberal arts. In this poem, the arts are competing for the crown of Mary.

Here we see Logic wearing a crown. In her right hand she holds a dove, in her left hand a serpent. According to the accompanying verses, the dove and serpent indicate that logic distinguishes between true (the dove) and false (the serpent).

https://digi.ub.uni-heidelberg.de/diglit/cpg14/0027

From the twelfth century onwards, Dialectic is presented with a variety of attributes alongside, or in place of, the traditional serpent. Scorpions, dogs, doves and flowers express her positive and negative side and demonstrate her power to attract and to hurt.

In this thirteenth-century manuscript of logical texts, Lyon, BM, Ms. 244, the inherent dualism that we have encountered so far in representations of dialectic has been resolved. Lady Dialectic is depicted as the virgin Mary. The serpent is not in her hand, but trampled under her feet. The beast still represents treacherous and seductive reasoning, but this time it is not Dialectic who employs it. To the contrary, it is she who conquers false and misleading arguments. The serpent has taken the position of the devil, the Old Serpent, who in traditional iconography is trampled under the feet of Christ.

http://initiale.irht.cnrs.fr/decor/5080

This gallery of verbal and visual images aimed to illustrate a development, in which dialectic gradually lost its controversial character the more it was integrated in the school curriculum, until it became the cornerstone of scholasticism. As a result, the art was regarded with less distrust. This development is reflected in the iconography of Lady Dialectic, who transformed from an untrustworthy, belligerent woman to the undisputed queen of the Trivium.

Sources used for this contribution:

Primary sources:

- Alanus de Insulis (Alain de Lille), Anticlaudianus, PL 210, 488-574.

- Alcuin, De dialectica, PL 101, 950-976.

- Cicero, Brutus, Orator, Translated by G. L. Hendrikson, H. M. Hubbell, Loeb Classical Library 342 (Cambridge, MA, Harvard University Press, 1939).

- Martianus Capella, De nuptiis Philologiae et Mercurii, trans. William Harris Stahl, Richard Johnson, Martianus Capella and the Seven Liberal Arts, vol. II: The Marriage of Philology and Mercurius (New York, 1977).

- Plato, Protagoras, trans. http://classics.mit.edu/Plato/protagoras.html

- Scoto Eriugena, Remigio di Auxerre, Bernardo Silvestre e anonimi. Tutti i commenti a Marziano Capella. Testo latino a fronte, ed. by Ilaria Ramelli (Milano, 2006).

Secondary literature:

- Lim, Richard, Public disputation, power and social order in late Antiquity (Princeton, 1991).

- Lindberg, D., ‘Science and the medieval church’, in D. Lindberg & M. Shank (ed.), The Cambridge History of Science (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2013), pp. 268-285

- Staub, Kurt Hans and Hermann Knaus, Die Handschriften der Hessischen Landes- und Hochschulbibliothek Darmstadt; Bd.4 (Wiesbaden, Harrassowitz, 1979).

Contribution by Irene van Renswoude. I thank Janneke Raaijmakers for her critical reading and always excellent suggestions for my contributions.

Cite as, Irene van Renswoude, “A controversial art?”, The art of reasoning in medieval manuscripts (Dec 2020), https://art-of-reasoning.huygens.knaw.nl/controversial-art. ↑

Cicero, Orator 1130. ↑

Pappas 2016, 77. ↑

Plato, Protagoras, trans.: http://classics.mit.edu/Plato/protagoras.html. ↑

Lindberg, 2013, 270. ↑

Martianus, De nuptiis, book IV, trans. Stahl, 107 ↑

ed. Stahl, 107 ↑

“Tortuose et fallaces et seductrices propositiones sunt” ed. Ramelli, 264. ↑

“Per tortuosos et nexiles crines significantur fallaces et seductrices propositiones”, ed. Ramelli, 1120. ↑

“Per serpentem, sophisticas subtilitates intellige”. ↑

Lim, 1995. ↑

Staub/Knaus, 245 ↑

Alanus de Insulis, Anticlaudianus, III, 1, 345, PL 210, col. 509. ↑

Next Read:

Next Read: