Abelard

A master of disputation1

Peter Abelard, or Petrus Abaelardus (c. 1079-1142) stands at the threshold of the age of scholasticism and the rise of the universities. He made a name for himself as a teacher of logic, just before the bulk of Aristotle’s writings became available again in the West. His learning represents the summit of the study of the logica vetus. Abelard is called ‘“the greatest logician of the middle ages” and the pioneer of the scholastic method.2

Abelard was born in 1079 in Le Pallet, a small town in Brittany. The details of his life are well-known from his autobiography, The Story of My Misfortunes (Historia calamitatum), in which he recorded the formative years of his studies, when he travelled to study with well-known teachers. He presents himself as an itinerant scholar: “I began travelling across several provinces disputing, like a true peripatetic philosopher, wherever I heard that the study of my chosen art most flourished.”3 Disputations would play a vital role in Abelard’s career, both as a student and as a teacher.

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Abelard_cour_Napoleon_Louvre.jpg

Abelard studied poetry, grammar, rhetoric and dialectic with Roscelin of Compiègne (d. 1125), who is often regarded as the founder of nominalism, perhaps at his school in Loches.4 It was here that Abelard’s fascination with dialectic as a language art was born. Roscelin represented a new type of teacher: a secular cleric who was free to move from school to school – a model that Abelard would later emulate.5 He went on to study dialectic with William of Champeaux (d. 1122) in Paris, at the cathedral school of Notre Dame. Abelard recounts in his autobiography that he fell out with William, when he defeated his master in argument.

http://initiale.irht.cnrs.fr/decor/105913

Abelard set himself up as a teacher, first at Melun and then in Corbeil, near Paris. Around 1113 another period of study followed. He went to Laon to study theology with Anselm (d. 1117) who enjoyed fame as an authority on Scripture and the church fathers.

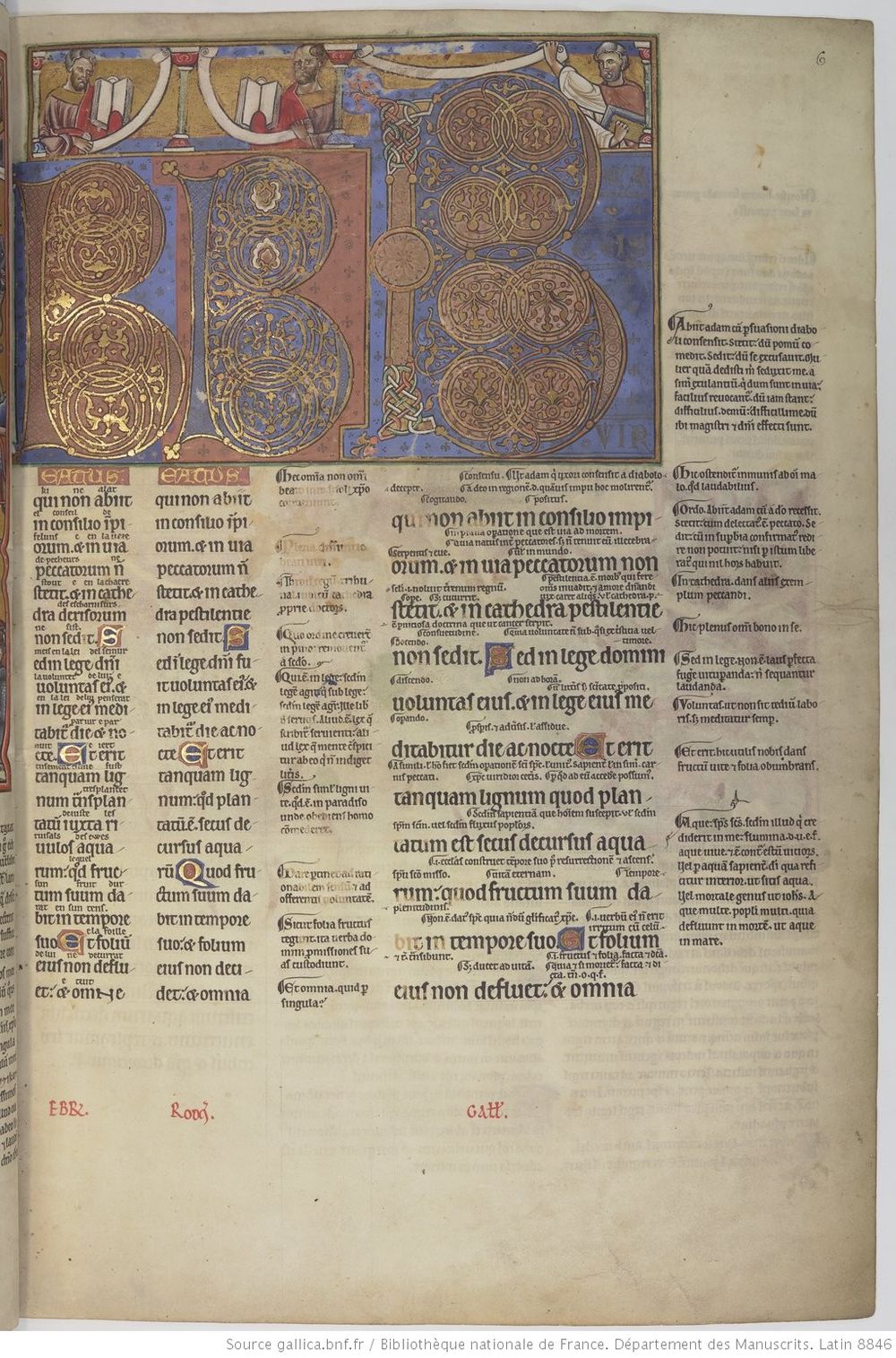

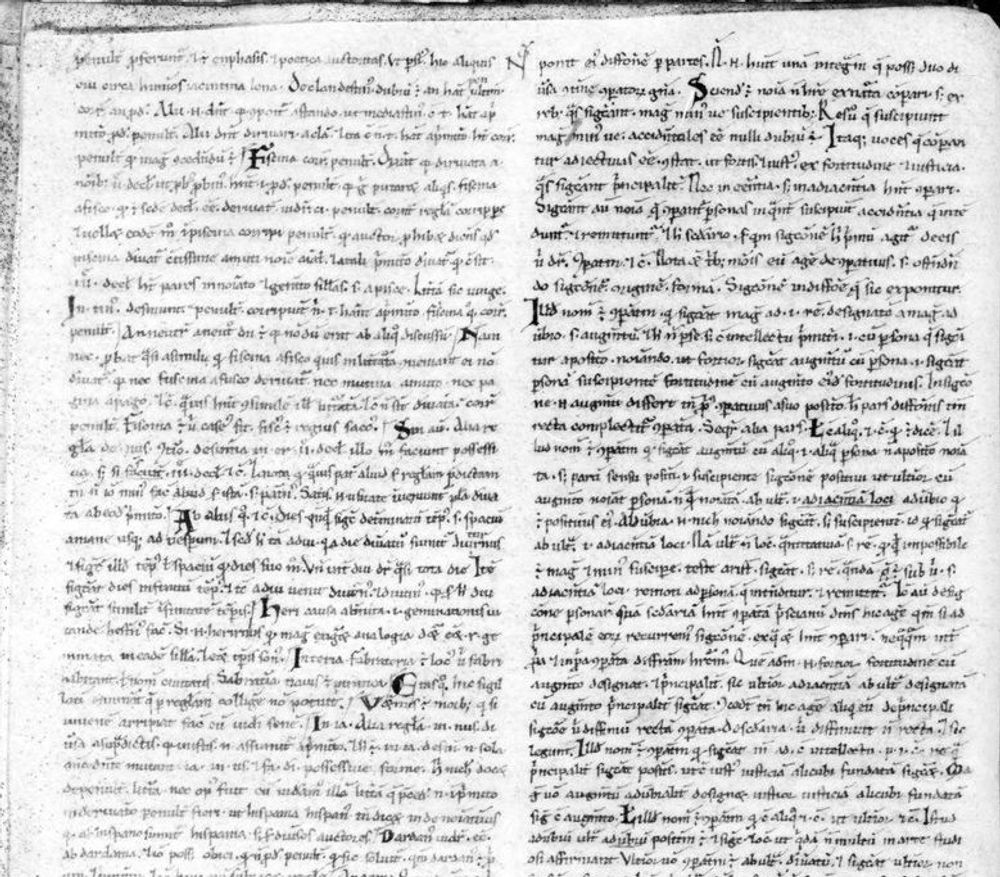

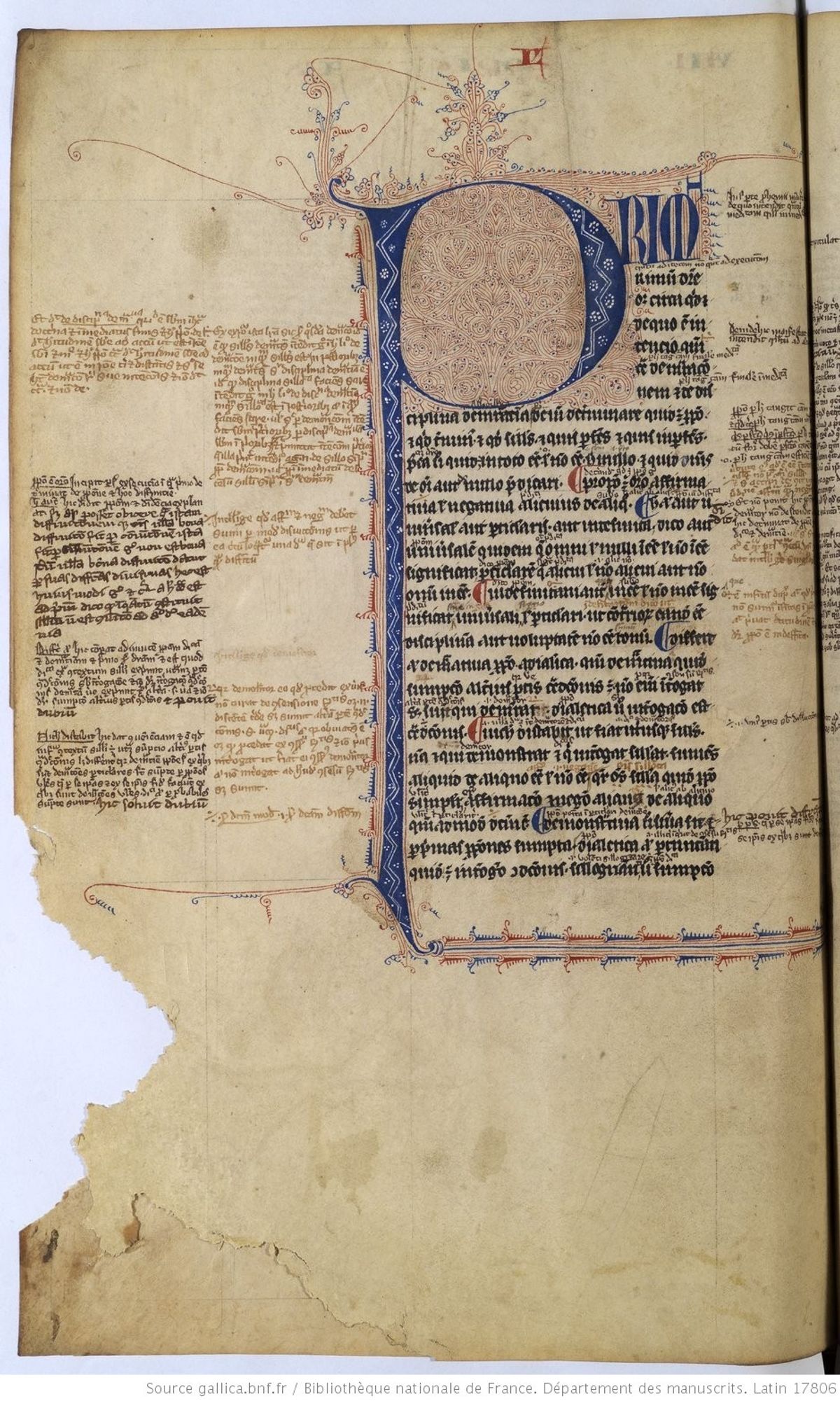

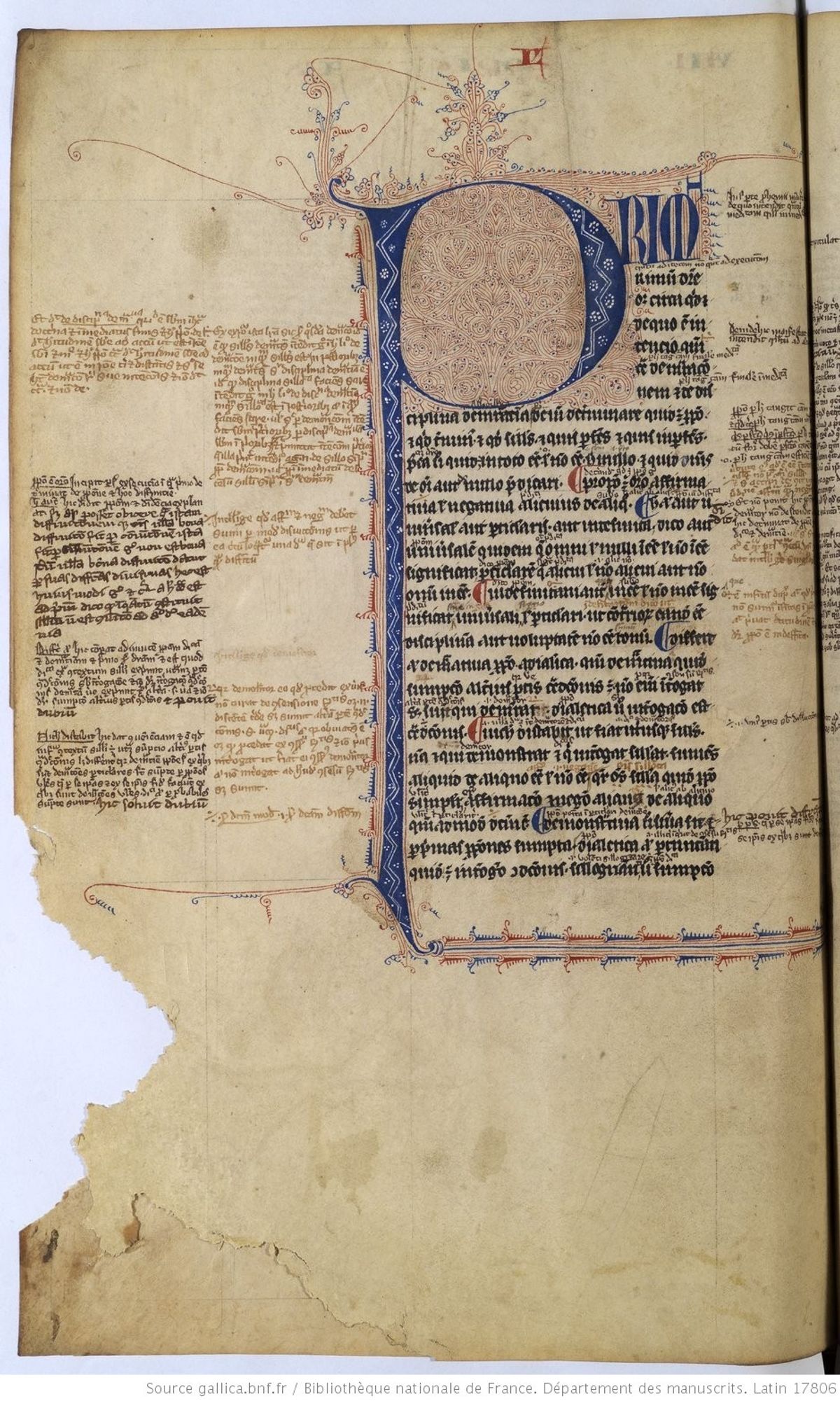

Here is an image of a twelfth-century Psalter copied in Christ Church Canterbury (ms. Paris, BnF, Latin 8846) with glosses attributed to Anselm of Laon. Folio 6r shows the opening of Psalm 1: "Beatus vir non abiit in consilio impiorum"; "Blessed is the man who does not walk in the counsel of the ungodly". To the right of the decorated initial B we read a gloss on the word 'abiit': "Adam abiit cu(m) p(er)suasioni diabo-/li consensit"; 'Adam walked when he agreed to the persuasion of the devil'. Anselm’s traditional approach, however, did not appeal to Abelard and he returned to Paris, where he became scholar-in-residence at Notre Dame.

https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b10551125c

Even though Abelard fell out with all his masters, his intellectual development owed much to the teaching of Roscelin, William, Anselm and to the disputations he had with them. He continued disputing his former masters in his logical and theological writings, in which he frequently formulated his own position on an issue in opposition to theirs.

http://initiale.irht.cnrs.fr/decor/95961

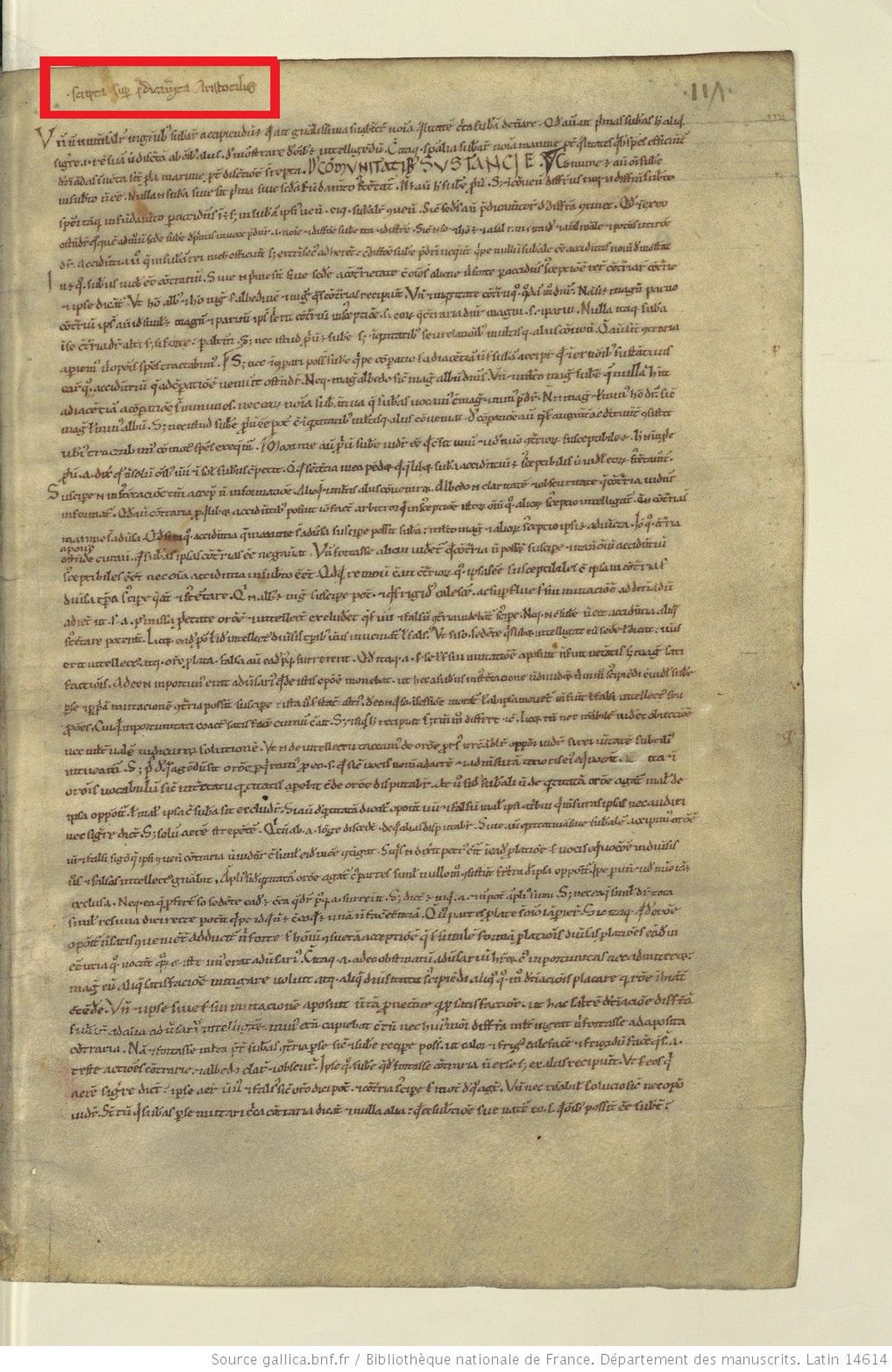

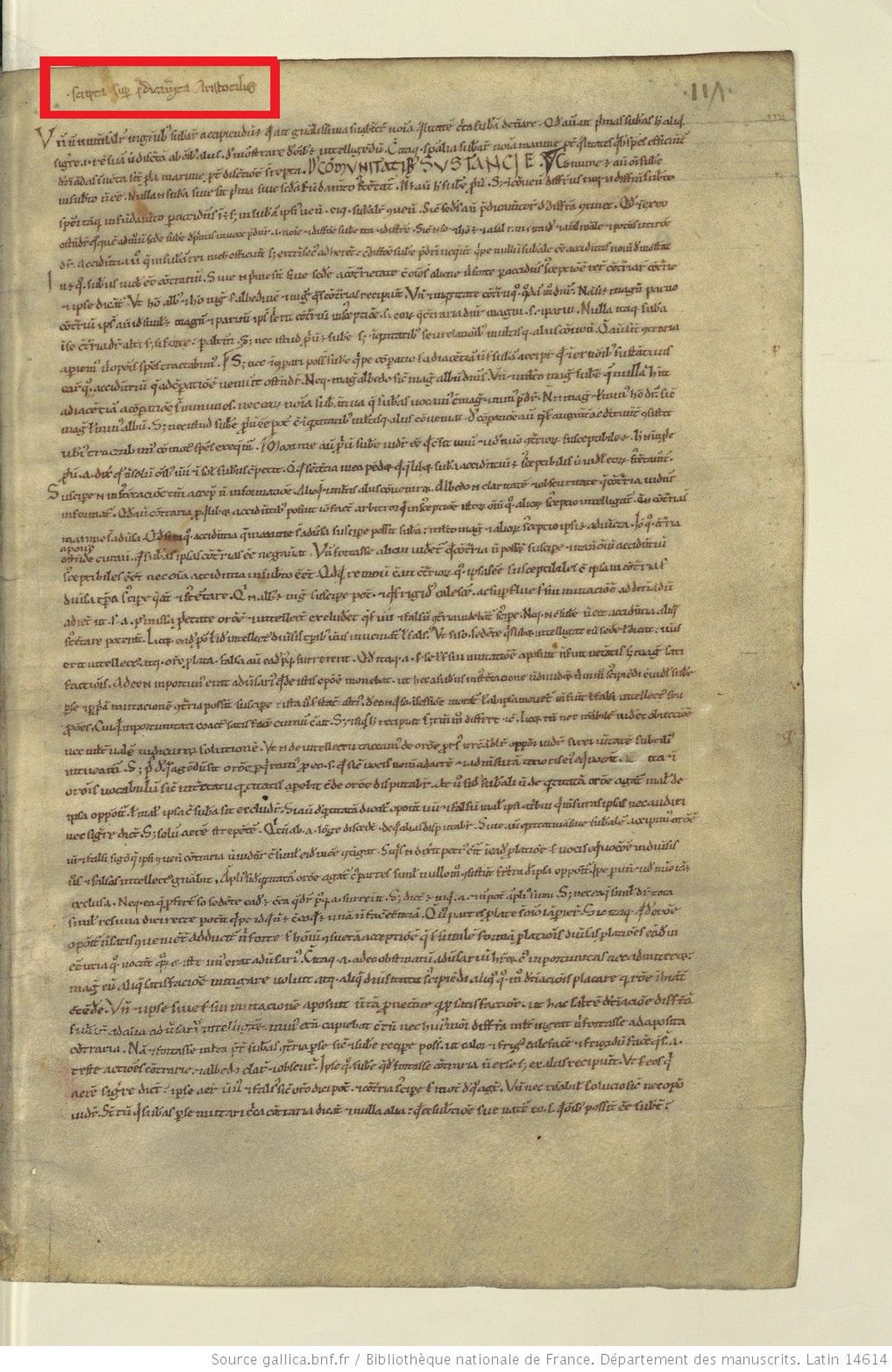

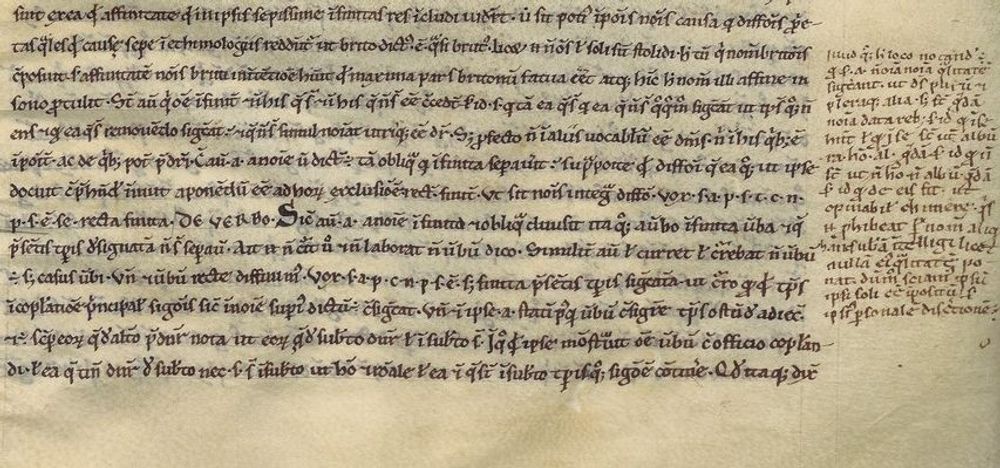

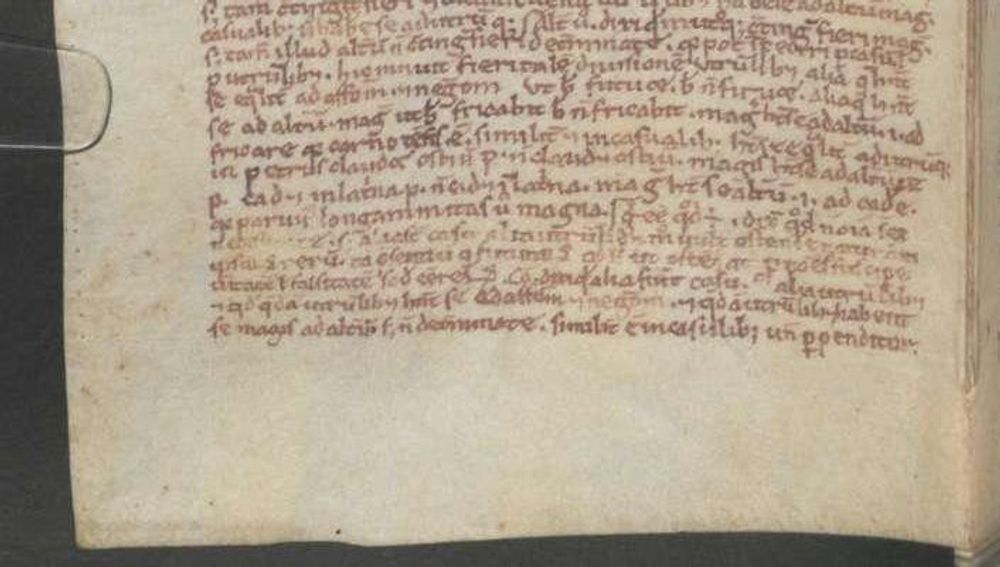

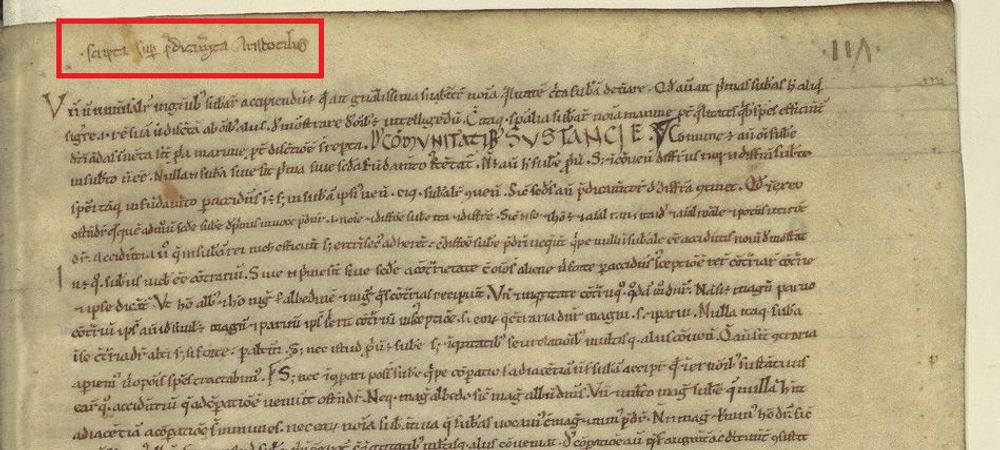

After returning from Laon, Abelard wrote the Dialectica, his first major treatise on dialectic, based on lectures he gave in Paris in 1115-6.6 It was probably completed by 1117-18.7 The book is dedicated to the education of the sons of his brother Dagobert. Abelard’s Dialectica has survived in only one manuscript: Paris, BnF, lat. 14614 (ff. 117-202), dated to the twelfth century. The manuscript belonged to the library of St. Victor in Paris.

The opening of the Dialectica is missing, but an identification of the text is written at the top of the page: ‘scripta super predicamenta Aristotilis.’

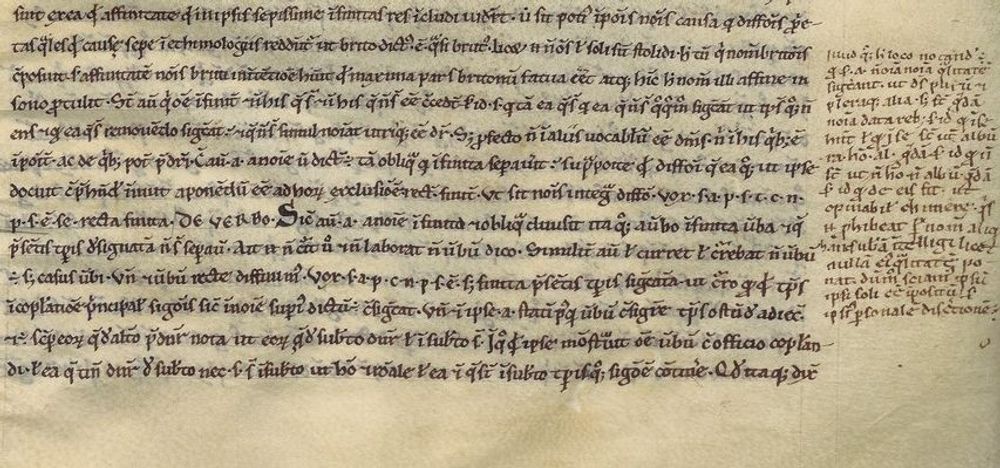

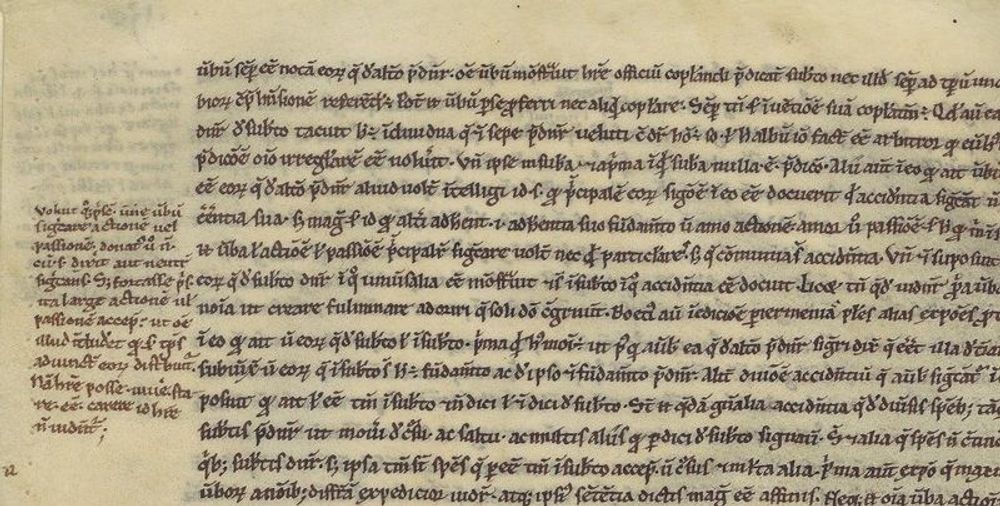

In manuscript Paris, BnF, lat. 14614 especially the section on “sententia vocis”, “the message of the word”, received relatively extensive annotations. Next to where Abelard pointed out that every verb signified an action or a passion, the note on folio 130 recto adds the interpretation of Donatus and the note on f. 130v that of Priscian. Constant Mews has suggested that the hand that made corrections and added notes in the margin could well be that of Abelard himself.8

https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b6000788f

Abelard’s Dialectic posed a challenge to traditional dialectic in the sense that it emphasized words and their meanings, rather than things (res).9 For Abelard, dialectic was above all an art of language. His semantic approach to dialectic was inspired by his teacher Roscelin, who considered words (voces) as the building blocks of all dialectic. Another source of inspiration was the anonymous Glosule on Priscian’s Grammatical Institutes that started to circulate by the late 1070s. The Glosule and other late eleventh- and early twelfth-century texts and teachers set the agenda for a discussion between ‘realists’ and ‘vocalists’, in the schools of northern France and Normany for the next 50 years.10

https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b100336143.r

Logic for beginners

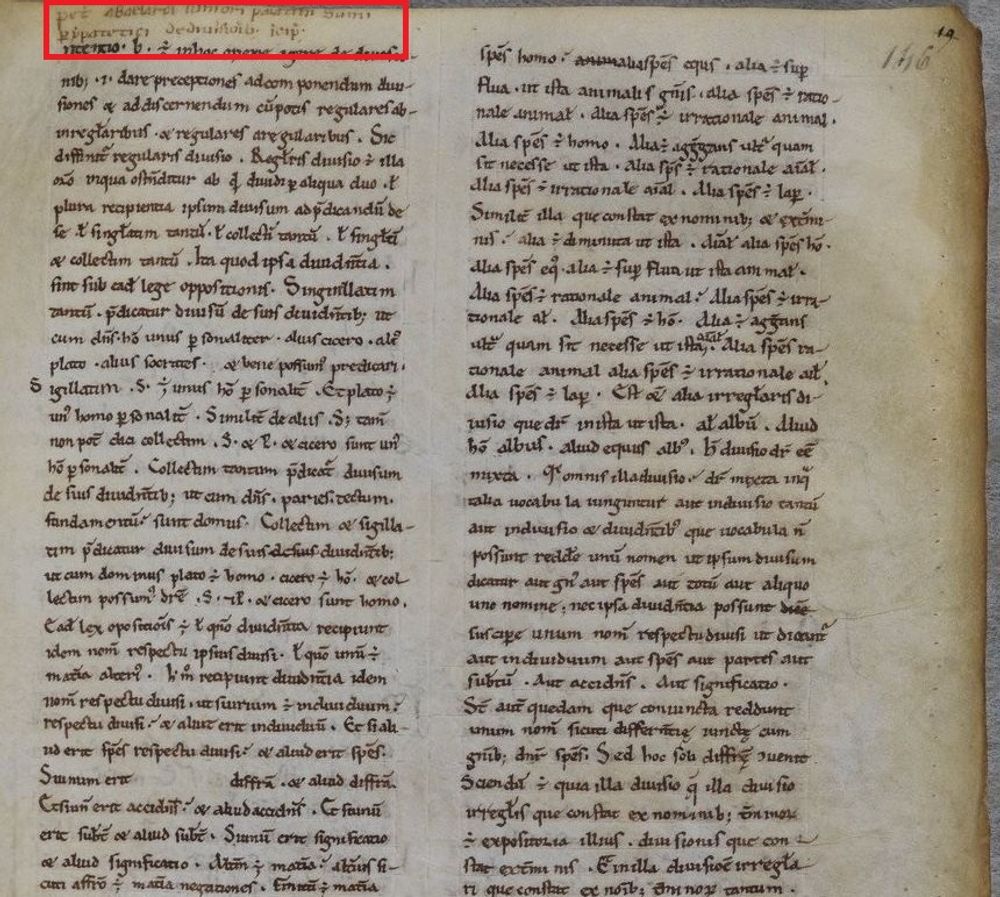

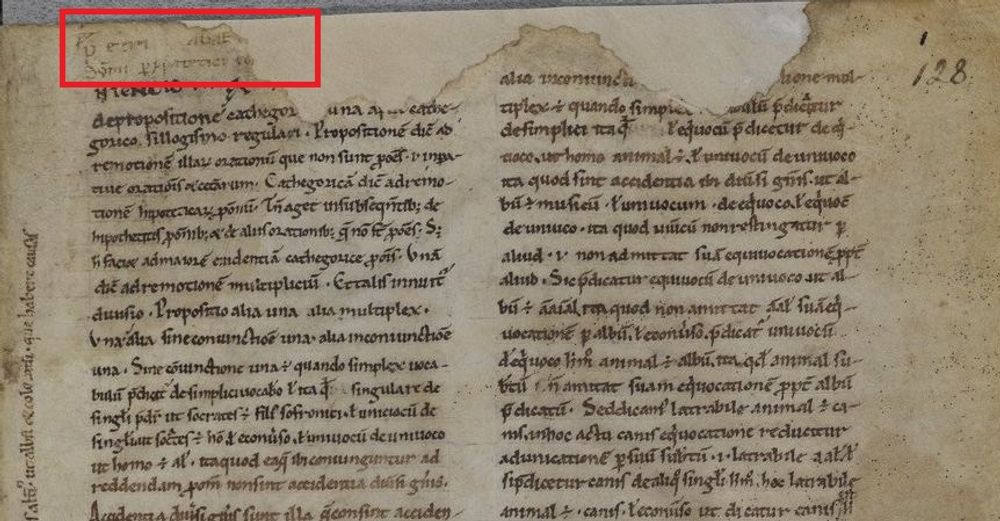

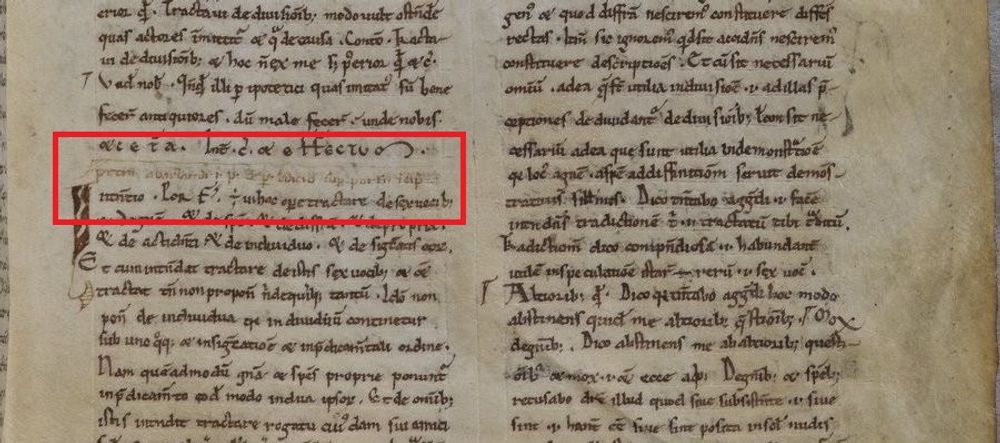

It is unclear when exactly Abelard composed the Introductiones parvulorum – Logic for beginners, a series of glosses on the standard texts of the logica vetus of Porphyry, Aristotle and Boethius. The Introductiones, which are basically a set of teaching notes, probably reflect Abelard’s teaching at an early stage of his career, before he wrote the Dialectica. Yet by the time the sole surviving manuscript of the Introductions was copied (Paris, BnF, lat. 13368) Abelard had gained a solid reputation as a teacher. Whereas most glosses on logical texts from the period have been transmitted anonymously, these glosses identify the author.11 Above the first column of a section on divisions, starting on folio 146 recto is written (here outlined in red by us): “Here begins Peter Abelard, the younger supreme peripatetic of Le Pallet, on divisions. ” (“petri abaelardi iunioris palatini summi peripatetici de divisionibus incipit”).

https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b52504523s

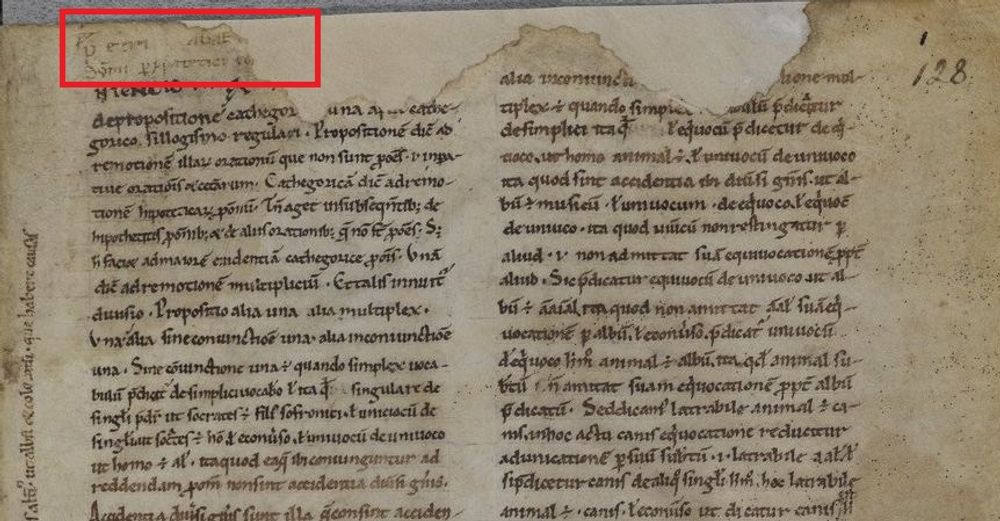

Another version of this attribution (but damaged) occurs at the start of the Introductions on folio 128 recto and another one on folio 156 recto, where it can be found next to Porphyry’s name. Whether the epithet ‘supreme peripatetic’ was Abelard’s own idea or that of one of his disciples is hard to tell. The fact remains that it is remarkable that the name of a modern commentator is identified, alongside the name of ancient authority. It reflects a new attitude to commentary as a textual genre.12

https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b52504523s

In the Logica ‘ingredientibus’ , his next series of glosses and commentaries on Porphyry, Aristotle and Boethius, (written between 1117 and 1121), Abelard mentions that he has carefully reread Aristotle’s Sophistical Refutations. This is an early reference to a text from the logica nova that would be studied intensively only from the 1130s onwards. By the 1120s Abelard had also encountered another text from the logica nova: Aristotle’s Prior Analytics. Yet Abelard does not seem to have studied these new Aristotelian texts in any depth, but consulted them mainly for reference. His main interest remained with the logica vetus.

Abelard’s logical works occasionally preserve classroom debates.13 He livened up his lectures with self-ironic examples to amuse his students and make dry logic more palpable, such as “His girl loves Peter” as the converse of “Peter loves his girl”. In a commentary on Porphyry’s Isagoge that has survived in manuscript Munich, BSB, Clm 14779 he made fun of his own slight stature when illustrating different types of contradiction:

“ … it can apply equally to both ‘Peter will close this door, Peter will not close this door’; or it relates more to another, as ‘Peter will fall into the latrine, Peter will not fall into the latrine’ relates more to falling, because he is small, even if great in forbearance.”14

urn:nbn:de:bvb:12-bsb00094630-4

Abelard’s logical works were little studied after the twelfth century, as they were written shortly before the influx of newly available Aristotelian treatises, which completely changed intellectual life in the thirteenth century. Abelard may have been the greatest and surely the most talked-about logician of the twelfth century, who was always in the centre of disputations and controversies, but soon his work was no longer relevant for contemporary debates.15

This section of the exhibition dealt with Abelard’s logical works. His theological writings, the ensuing condemnations, and his illicit love affair with Heloise d’Argenteuil, who would become abbess of the Paraclete, are discussed in other sections

Go to: Women and disputation & Manuscript portrait of Paris, BnF, lat. 2923.

http://initiale.irht.cnrs.fr/en/decor/78892

Sources used for this contribution:

- Iwakuma, Yukio, ‘Pierre Abélard et Guillaume de Champeaux dans les premières années du XIIe siècle: une étude préliminaire’, in: J. Biard (ed) Langage, Sciences, Philosophie au XIIe Siècle (Vrin, Paris, 1999), pp 93–124

- King, Peter and Arlig, Andrew, "Peter Abelard", The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Fall 2018 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.), URL = <https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/fall2018/entries/abelard/>.

- Mews, Constant J., Abelard and Heloise. Great Medieval Thinkers (Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, 2005)

- Mews, Constant J., ‘Interpreting Abelard and Heloise in the fourteenth and early fifteenth centuries. The criticisms of Christine de Pizan and Jean Gerson’, in P. J. J. M. Bakker, E. Faye, & C. Grellard (eds.), Chemins de la pensee medievale. Etudes offertes a Zenon (Turnhout: Brepols Publishers, 2002), pp. 709-724)

- Novikoff, Alex James, ‘Peter Abelard and Disputation: A Reexamination’, Rhetorica vol. 32 (2014) p. 323-347

Contribution by Irene van Renswoude. I thank Janneke Raaijmakers for her critical reading and always excellent suggestions for my contributions.

Cite as, Irene van Renswoude, “Abelard”, The art of reasoning in medieval manuscripts (Dec 2020), https://art-of-reasoning.huygens.knaw.nl/abelard. ↑

King, Arlig, 2018. ↑

Trans. Novikoff, 2014, 325. ↑

On nominalism, see below. ↑

Mews, 2005, 21. ↑

King, Arlig, 2018. ↑

Mews, 2005, 56. ↑

Mews, 2005, 47, note 19 and 260. ↑

Mews, 2005, 56. ↑

Mews, 2005, 28. ↑

Mews, 2004, 33. ↑

Mews, 1999, 71. ↑

Novikoff 2014, 331. ↑

“similiter in casualibus habet se aequaliter ad utrumque ut petrus claudet ostium p. not claudet ostium magis habet se ad alterum ut p. cadet in latrina<m> p. non cadet in latrina<m> magis habet se <ad> alterum, id est ad cadere, quia parvus longanimitas vero magna”, ed. Iwakuma, 1999, 95, translation Mews, 2005, 35. ↑

Mews 2002, 710. ↑

Next Read:

Next Read: