Gerard d’Abbeville

Master at the University of Paris1

Gerard d’Abbeville was a secular master of theology at the University of Paris. Unlike his contemporaries, the Dominican Thomas Aquinas and the Franciscan Bonaventure, Gerard did not belong to any of the new religious orders founded in the thirteenth century.

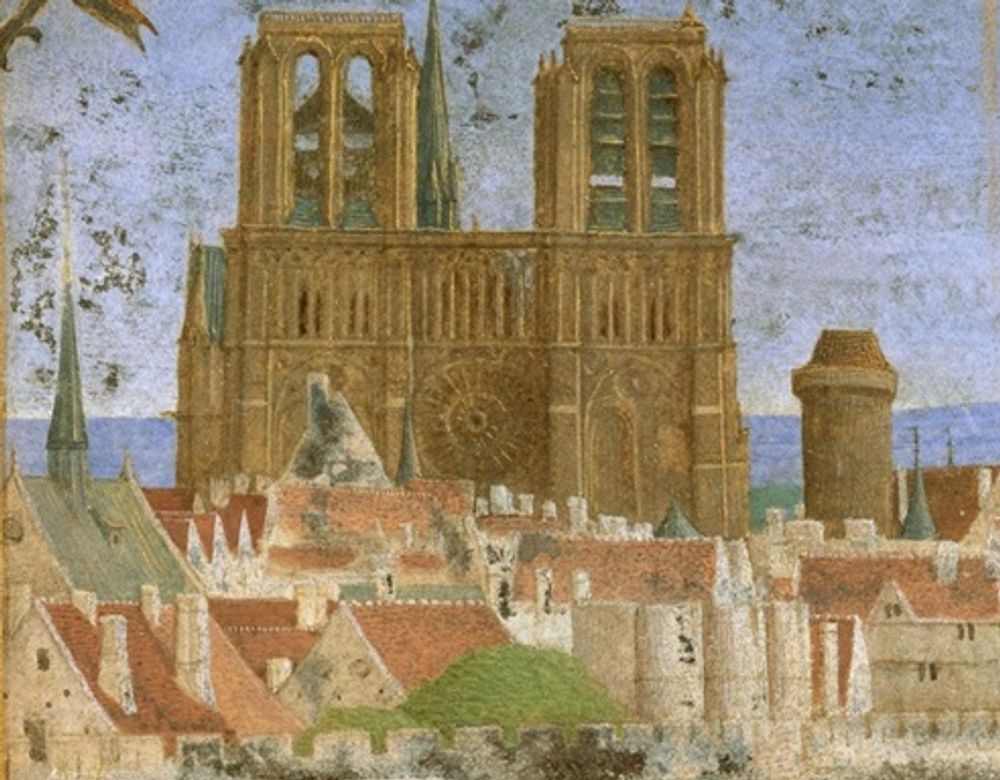

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Paris_in_the_Middle_Ages#/media/File:La_Descente_du_Saint-Esprit.jpg

In the mid-thirteenth century, conflicts arose at the newly formed University of Paris between secular masters (like Gerard) and teachers from the Franciscan and Dominican orders. These conflicts concerned practical issues – such as competing claims to students and positions of privilege – as well as theological matters, such as the spiritual value of personal poverty. Both sides published quodlibeta, records of disputations made in a question-and-answer format.

In 1269 Gerard held a quodlibet claiming that archdeacons and parish priests were in a higher state of spiritual perfection than members of religious orders. Gerard’s views were criticised by the Dominican Thomas Aquinas in his De perfectione spiritualis vitae (1269-70). This exchange illustrates the lively atmosphere of scholarly debate in Paris in this period. Eighteen quodlibeta of Gerard survive, a record!

https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b52506839q

Library of the Sorbonne

Gerard was a friend and colleague of Robert de Sorbon, who founded the college of the Sorbonne in 1253. Gerard’s commitment to the institution is evident from his will (1272). He bequeathed the library about 300 manuscripts, doubling the existing collection of the college. Libraries in this period were frequently built up by private donation, but the scale of Gerard’s donation is impressive.

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Fa%C3%A7ade_de_la_chapelle_Sainte-Ursule,_Sorbonne,_Paris.jpg

In his will Gerard stipulated that his books – mainly theological works, but also philosophical and medical manuscripts – could be freely used at the Sorbonne by all secular students and masters, subtly excluding access to them by his old sparring partners, the members of the mendicant orders. The religious orders, he commented, already had enough. As well as the books, Gerard donated his book cupboard (armarium) and three of his “best chests” to store the library, insisting that the collection was to be inspected yearly and inventorised. Gerard’s stipulations hint at the formalisation of institutional library practices in this period.

Ramon Llull was also a frequent user of the library of Sorbonne. In 1311 he donated a copy of his works to the library and requested that it would be chained to the bookcase; a common but not so subtle way of preventing a book from being stolen.

Where did Gerard get his books?

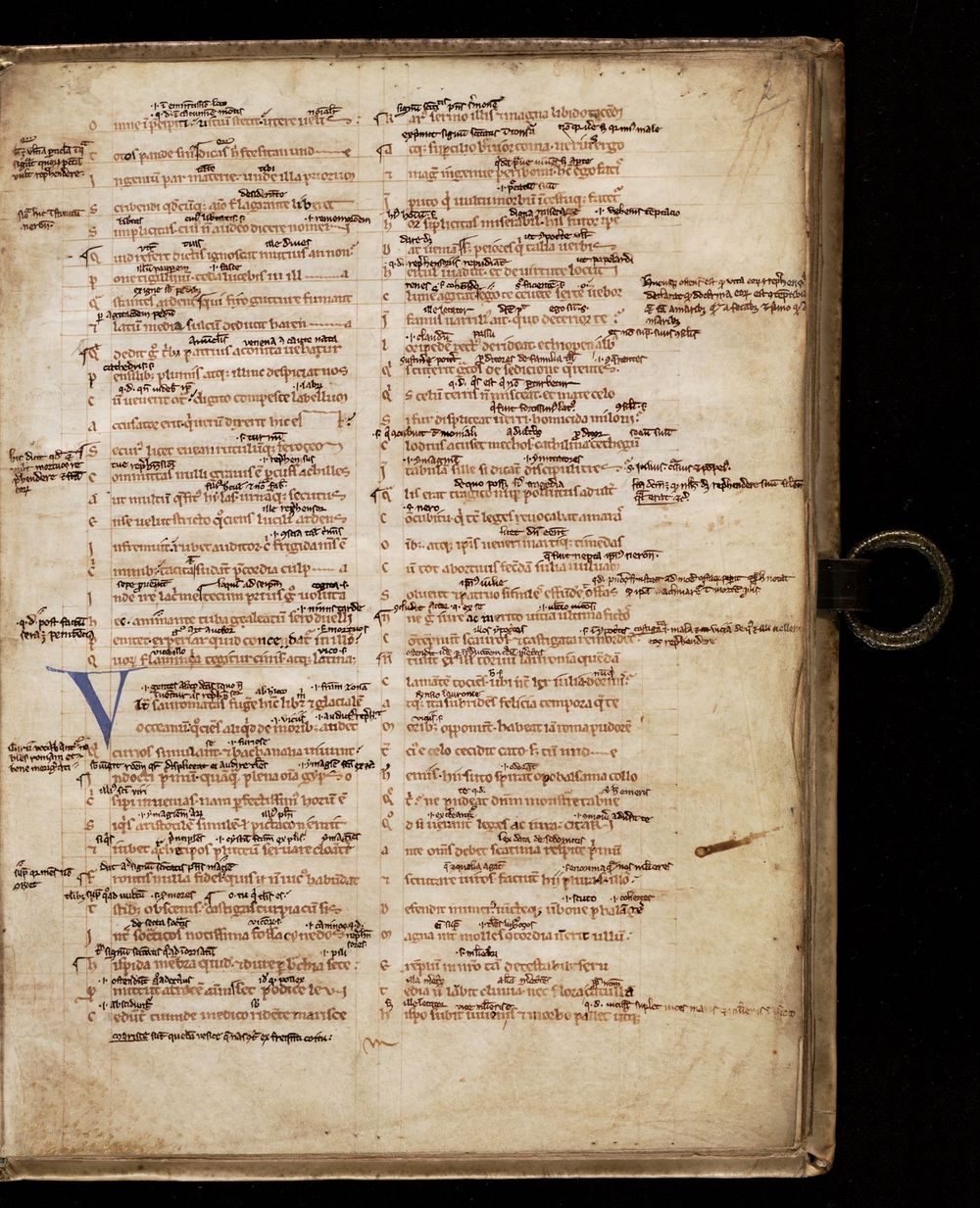

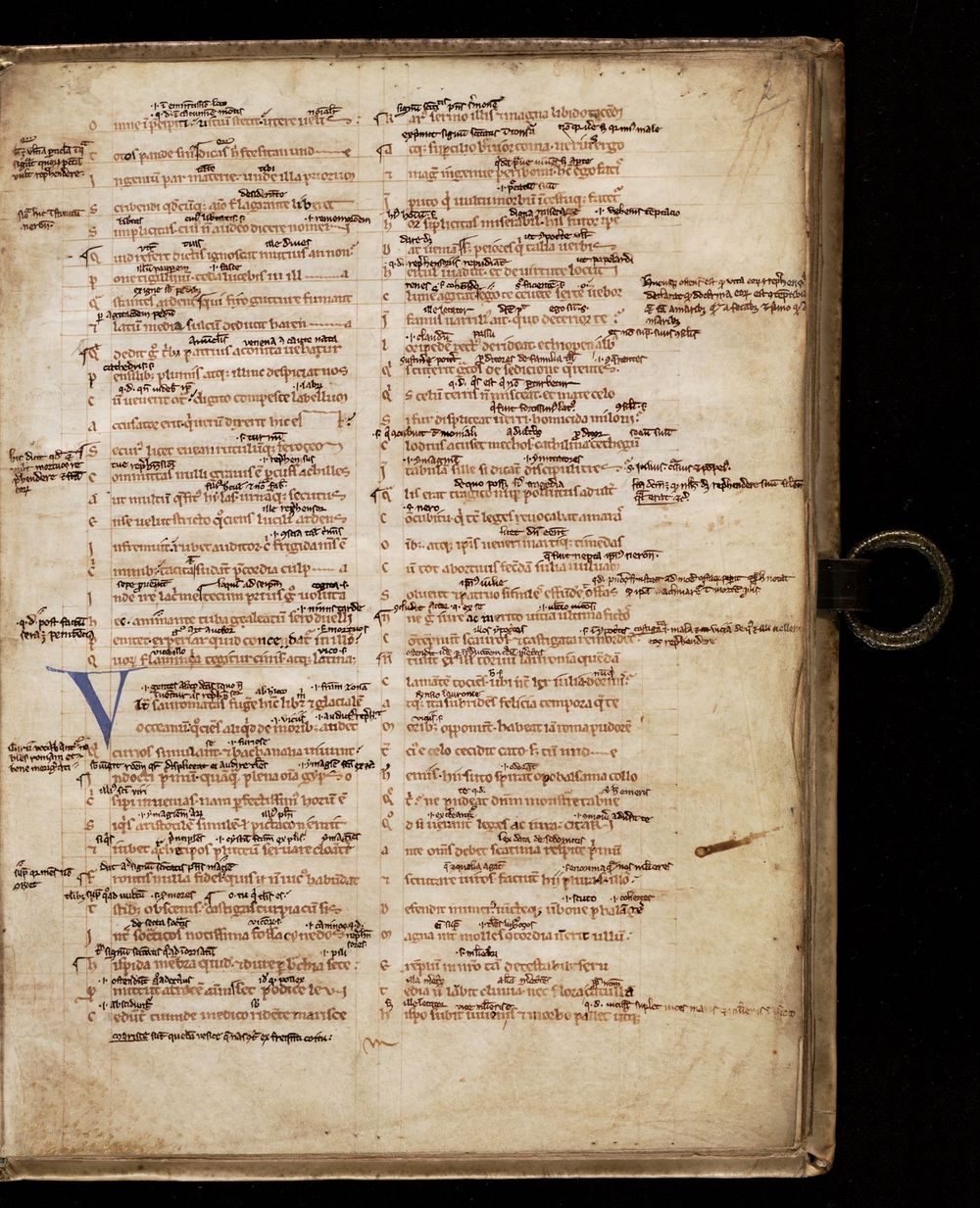

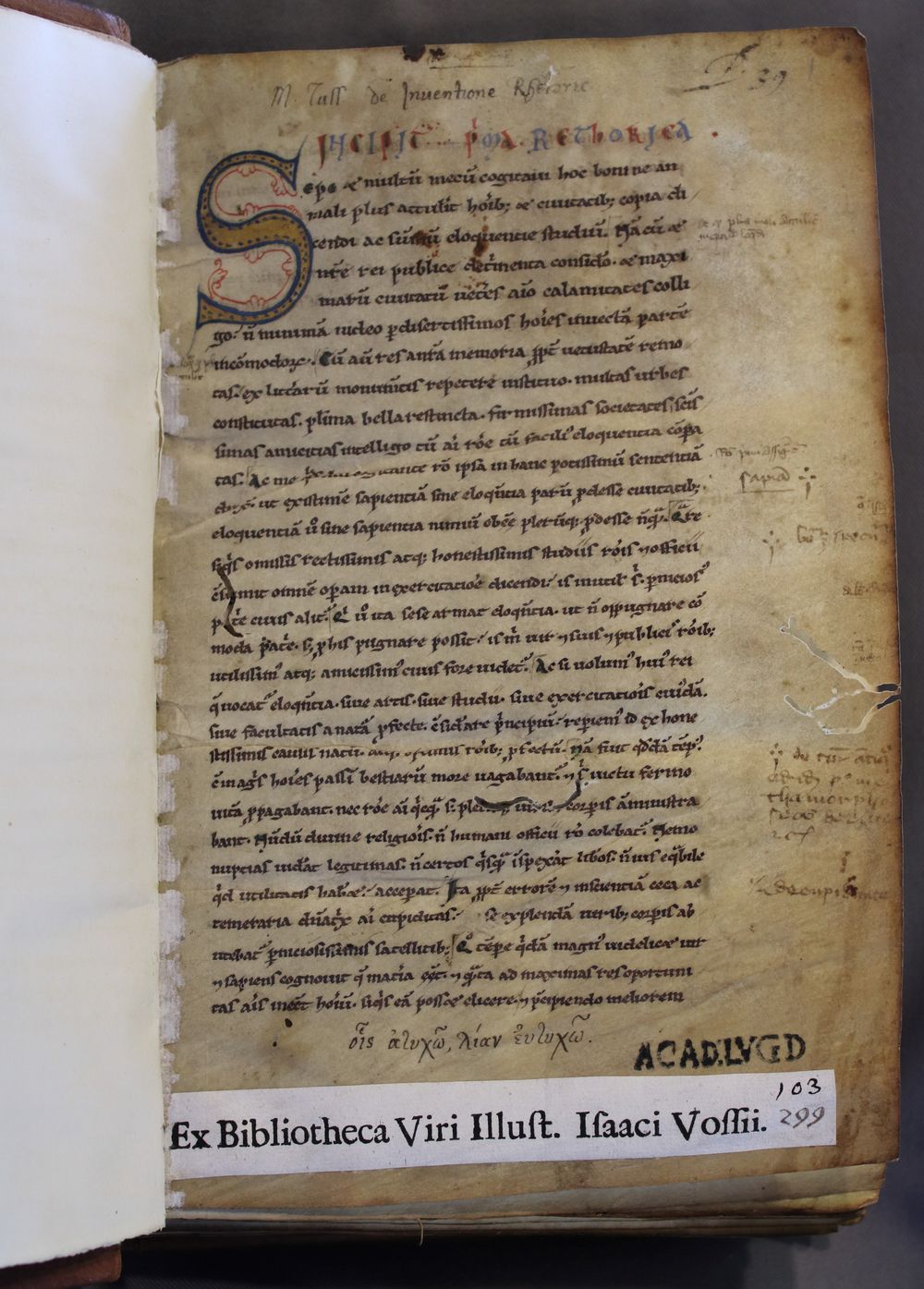

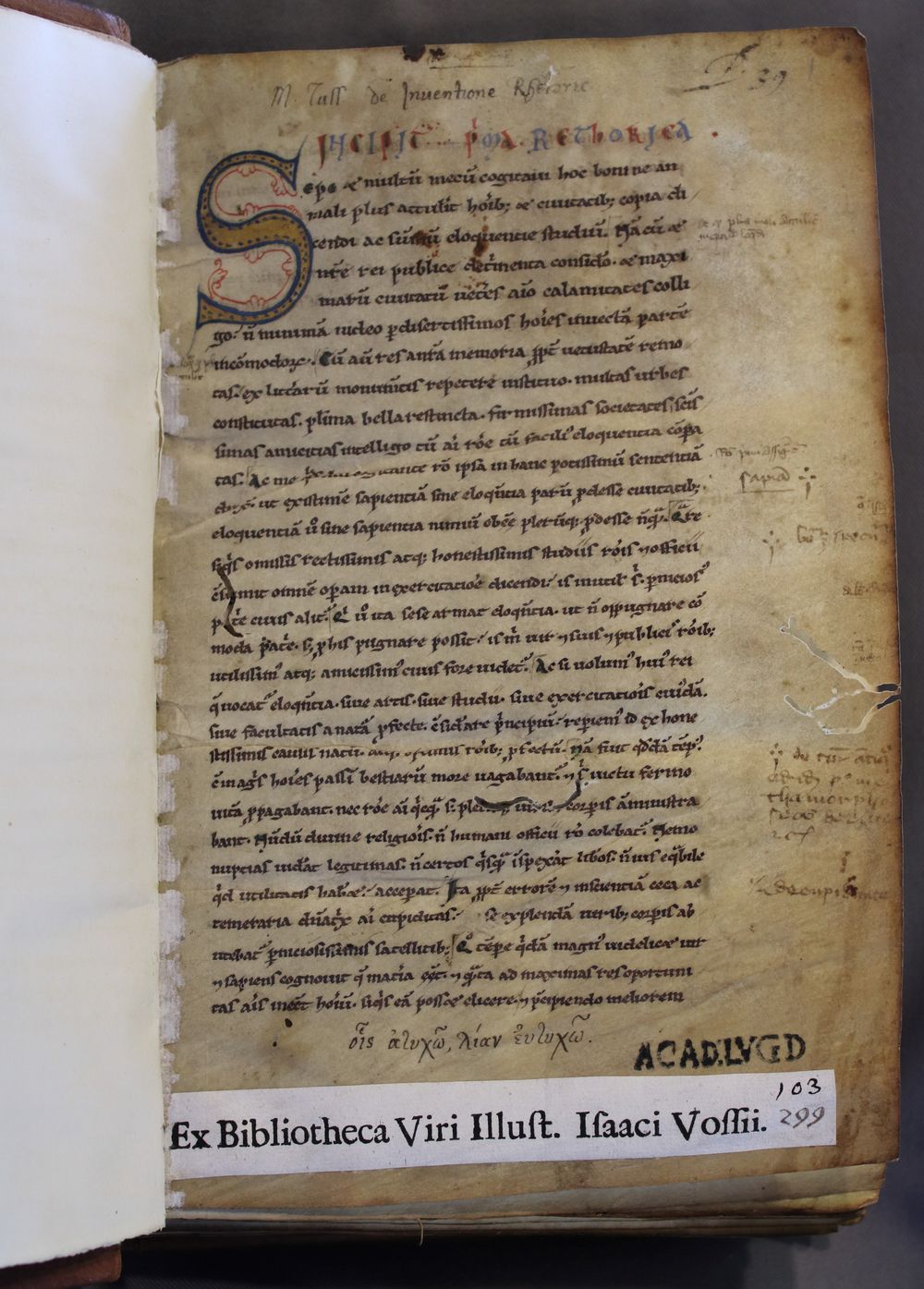

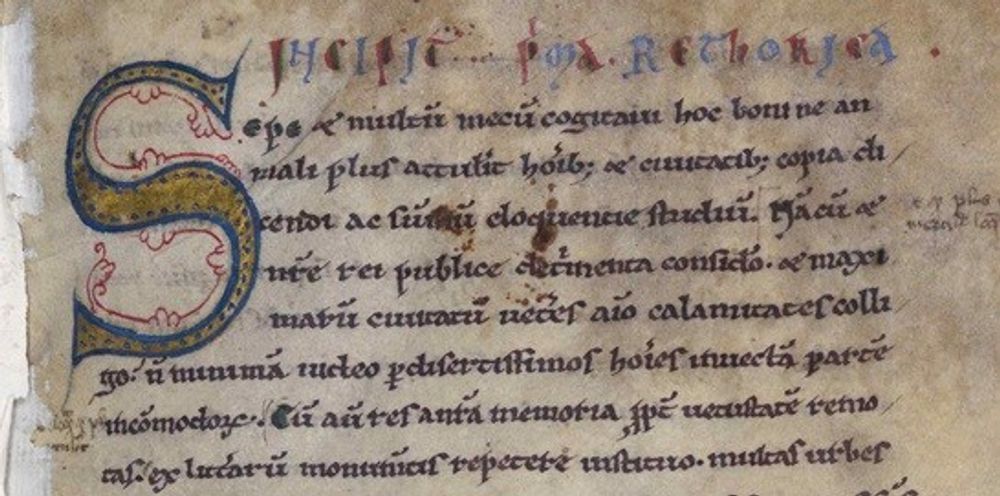

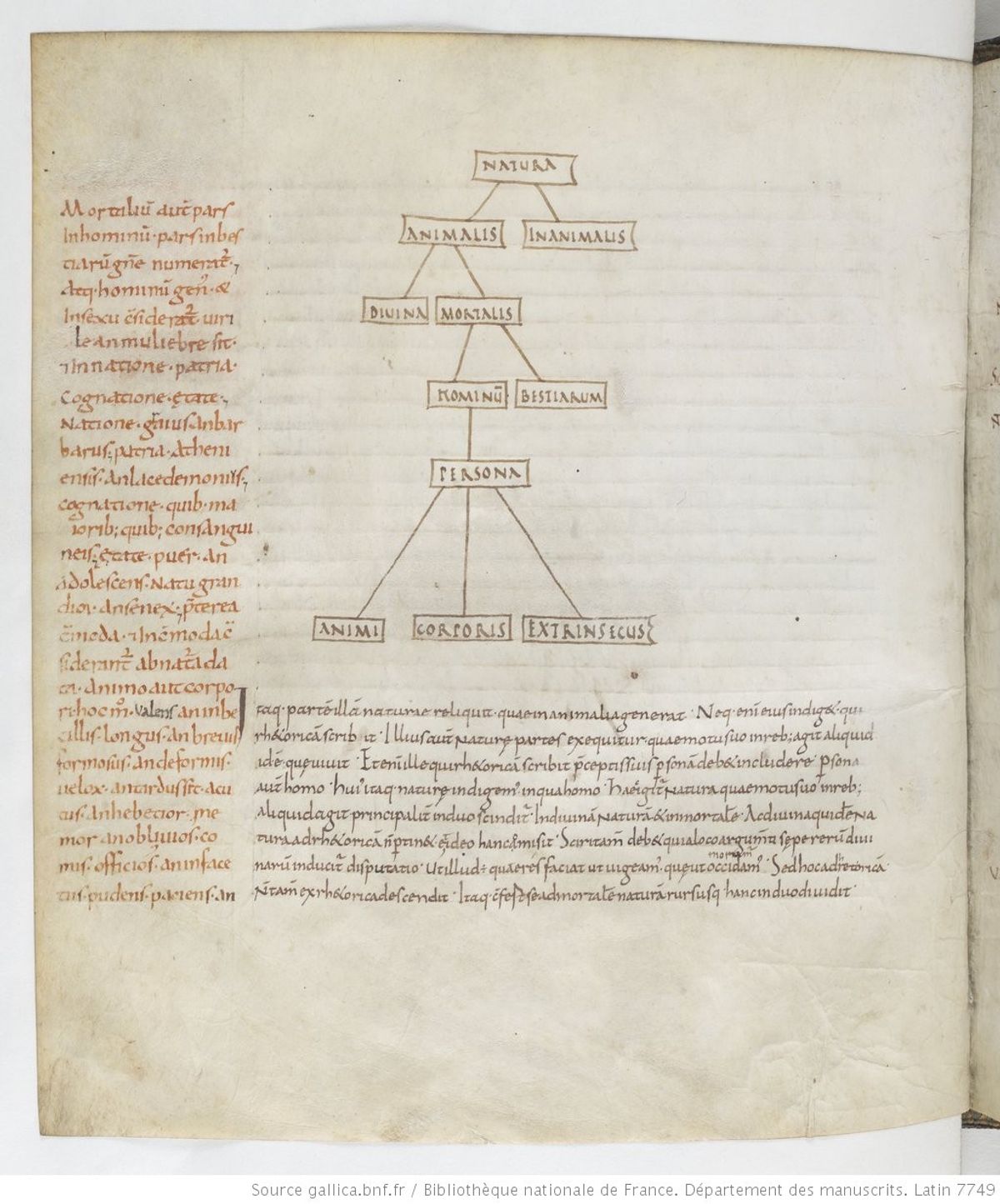

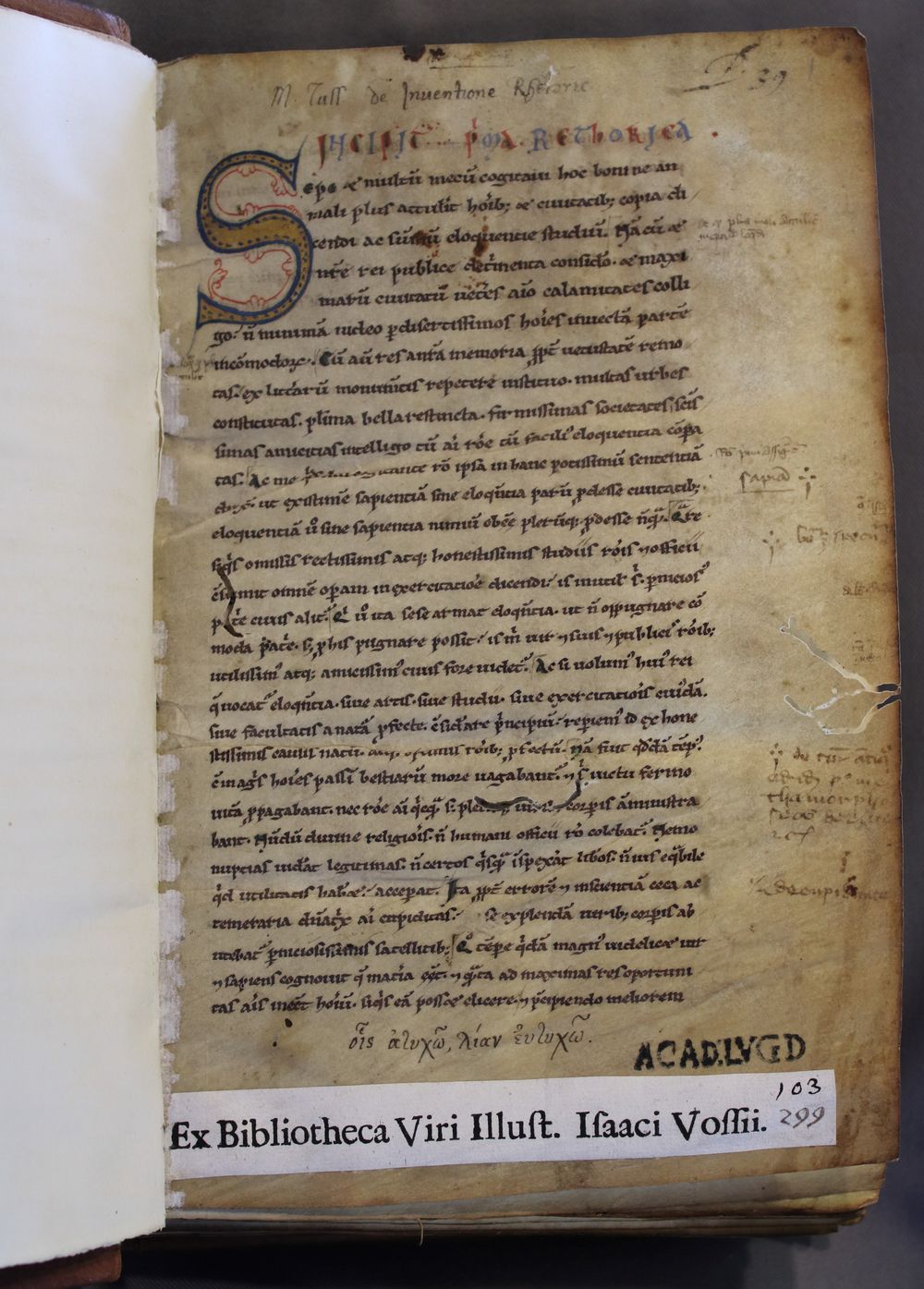

Many of Gerard’s books belonged to Richard de Fournival (d. 1260), a thirteenth-century poet, medic and astrologer who was Chancellor at the cathedral in Amiens. Richard wrote a catalogue of his books, Biblionomia (now Paris, Bibliothèque de Sorbonne, MS 636), which classified his manuscripts by subject, listing titles which were ‘must haves’ for medieval scholars. These included key works of rhetoric and dialectic: of Aristotle, Boethius, and Cicero, but also of the Islamic philosopher Al-Ghazali (c. 1056-1111) and the Spanish philosopher and translator of Arabic works, Dominicus Gundissalinus (c. 1115-90). Here you can see the opening of Cicero’s De inventione in Leiden, UB, VLQ 103, f. 1r. This manuscript was part of Richard’s collection (Biblionomia, 27), before being included in Gerard d’Abbeville’s bequest to the Sorbonne. Richard’s entry (translated) for this book reads: “[Cicero’s] first book on rhetoric and his second ad herennium in one volume whose sign is the letter C”, the letter indicating the classification of the manuscript in his collection (see Paris, Bibliothèque de Sorbonne, MS 636, f. 9r).

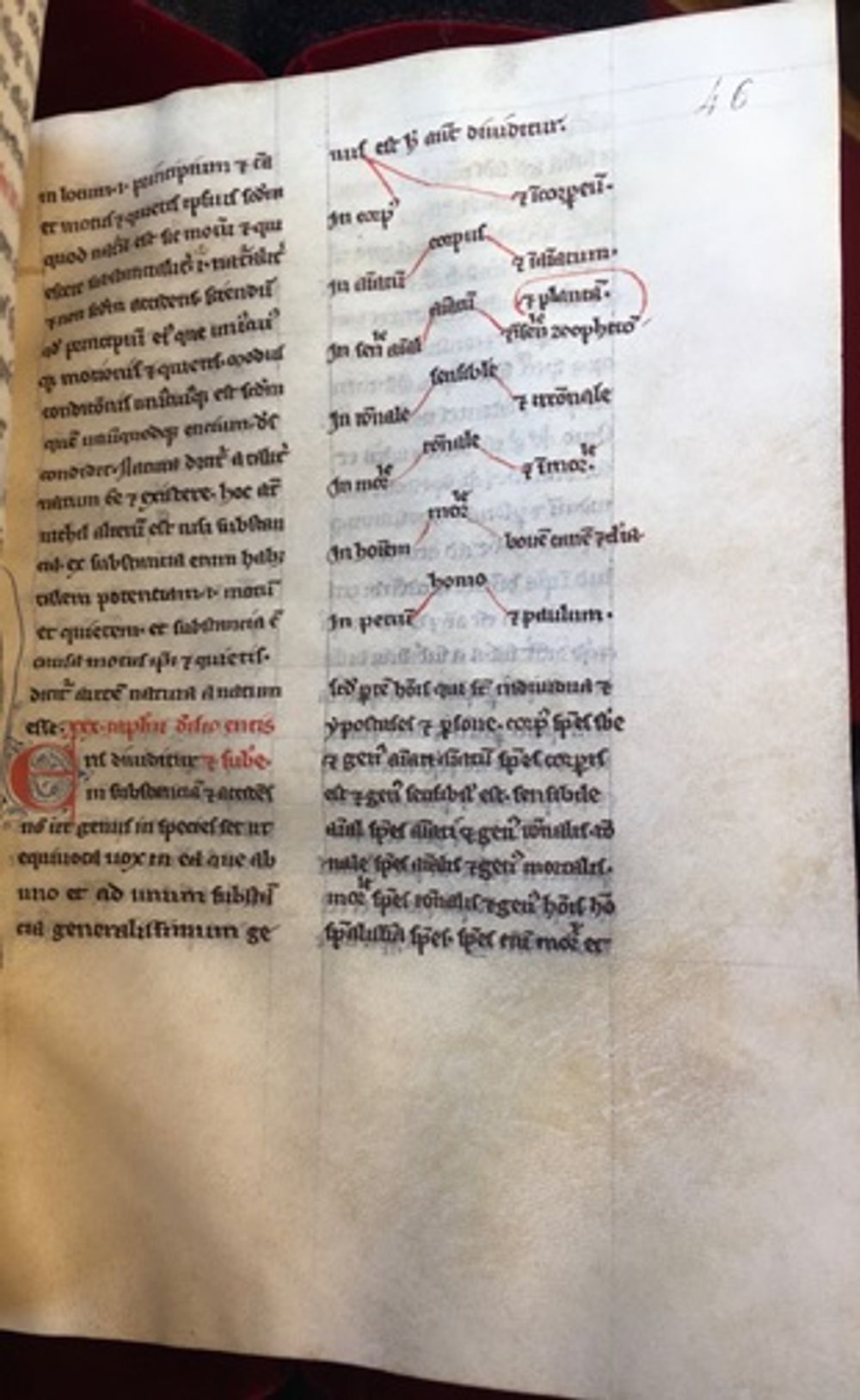

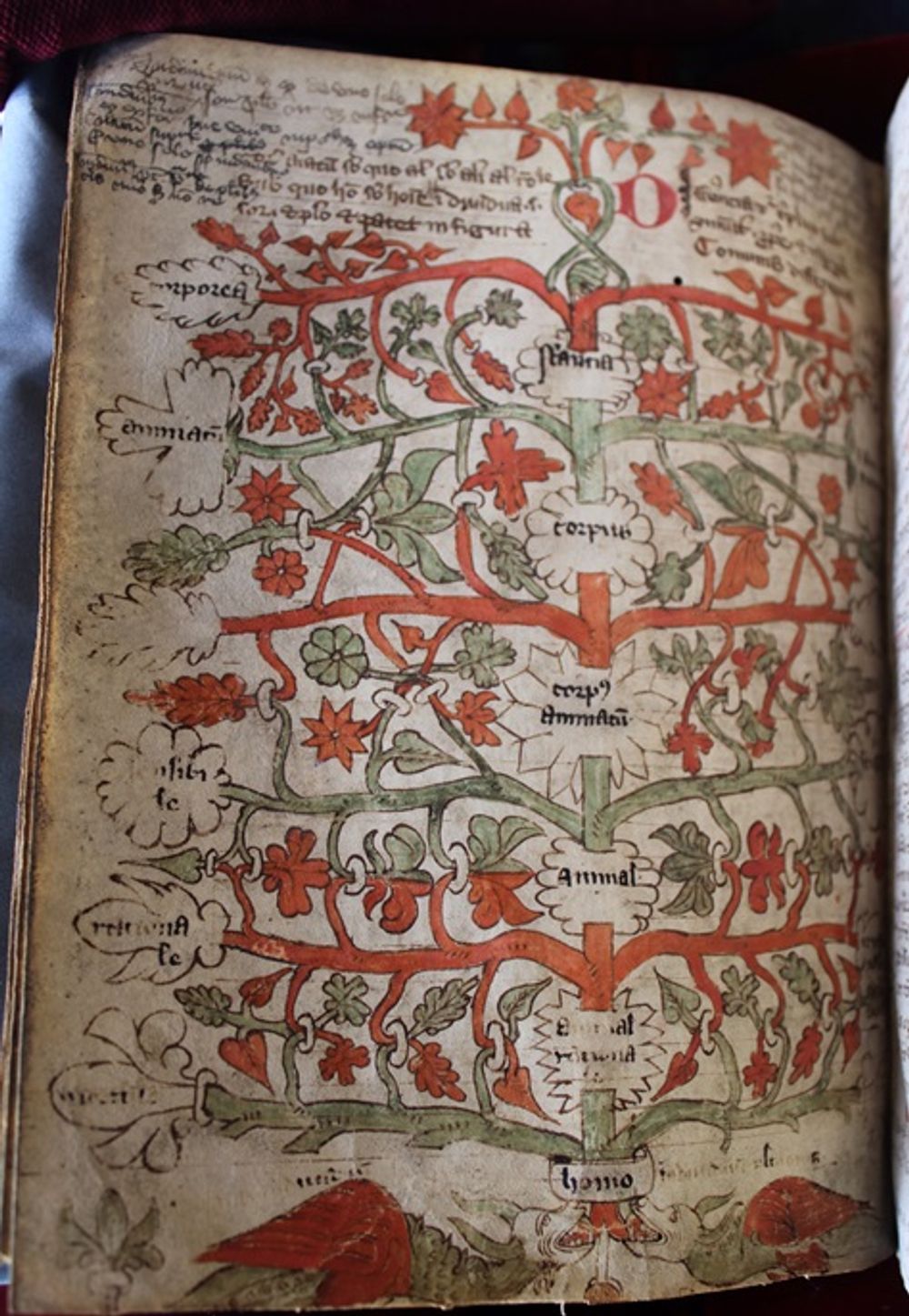

Richard’s collection also included older manuscripts, which were then passed on through Gerard into the Sorbonne’s collection. This copy of Victorinus’s fourth-century commentary on Cicero’s De inventione, for example, dates from the late-ninth century and was copied in a monastery in the Loire area in France.

Libraries and collectors preserved manuscripts, and so texts, which otherwise could have been easily lost. Gerard’s collection gives a sense of what the library of a thirteenth-century college would have looked like, including samples of rhetorical and dialectical works. However, Gerard clearly valued his collection of theological manuscripts far above his ‘philosophical’ works, advising in his will that his medical and philosophical works could be sold if needed to settle his debts! It’s lucky for us that they weren’t…

Click through to find out more about the content of some of Gerard’s books:

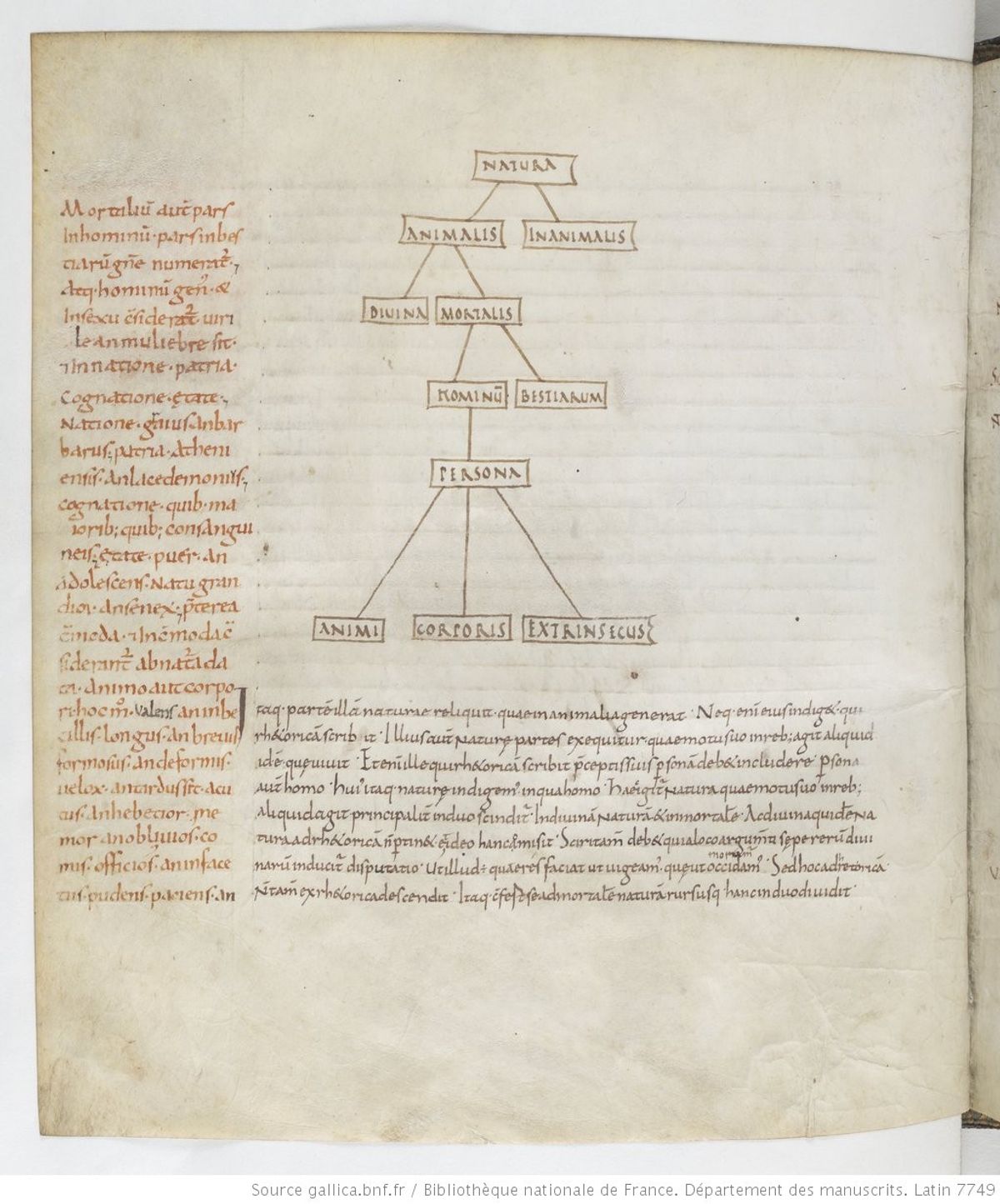

Find out about these ‘trees’ which represent logical concepts in Paris, BnF, lat. 16598 and Paris, BnF, lat. 16611. Explore Leiden UB, MS VLQ 103 in detail.

https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b9076885z

https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b90768515

Sources used for this contribution:

- Glorieux, P., Aux origines de la Sorbonnne: II. Le cartulaire (Paris, J. Vrin, 1965)

- Lucken, C., ‘La Biblionomia et la bibliothèque de Richard de Fournival: Un ideal du savoir et sa réalisation ’ in C. Agnotti, G. Fournier, D. Nebbiai (eds), Les livres des maîtres de Sorbonne: Histoire et rayonnement du college et de ses bibliothèques du XIIIe siècle à la Renaissance (Paris, Éditions de la Sorbonne, 2017; accessed on OpenEdition Books, DOI : 10.4000/books.psorbonne.28921)

- Metzger, S. M., Gerard of Abbeville, Secular Master, on Knowledge, Wisdom and Contemplation, vol. I (Leiden, Brill, 2017)

- Riesenweber, T., C. Marius Victorinus, Commenta in Ciceronis Rhetorica: Band 1: Prolegomena und Kritischer Kommentar (Berlin, De Gruyter, 2015)

- Rouse, R.H., ‘The early library of the Sorbonne’, Scriptorium, 21 (1967), 42-71

- Rouse, R. H., ‘Manuscripts belonging to Richard de Fournival’, Revue d'histoire des textes, 3 (1974), 253-269

- Rouse, R. H. and Rouse, M. A., Authentic witnesses: Approaches to medieval texts and manuscripts (Notre Dame IN, University of Notre Dame Press, 1992)

Contribution by Irene O’Daly in collaboration with Renée Schilling.

Cite as, Irene O’Daly and Renée Schilling, “Gerard d’Abbeville”, The art of reasoning in medieval manuscripts (Dec 2020), https://art-of-reasoning.huygens.knaw.nl/gerard. ↑

Next Read:

Next Read: