Paris, BnF, lat. 12949

A treasure trove of logic and reasoning1

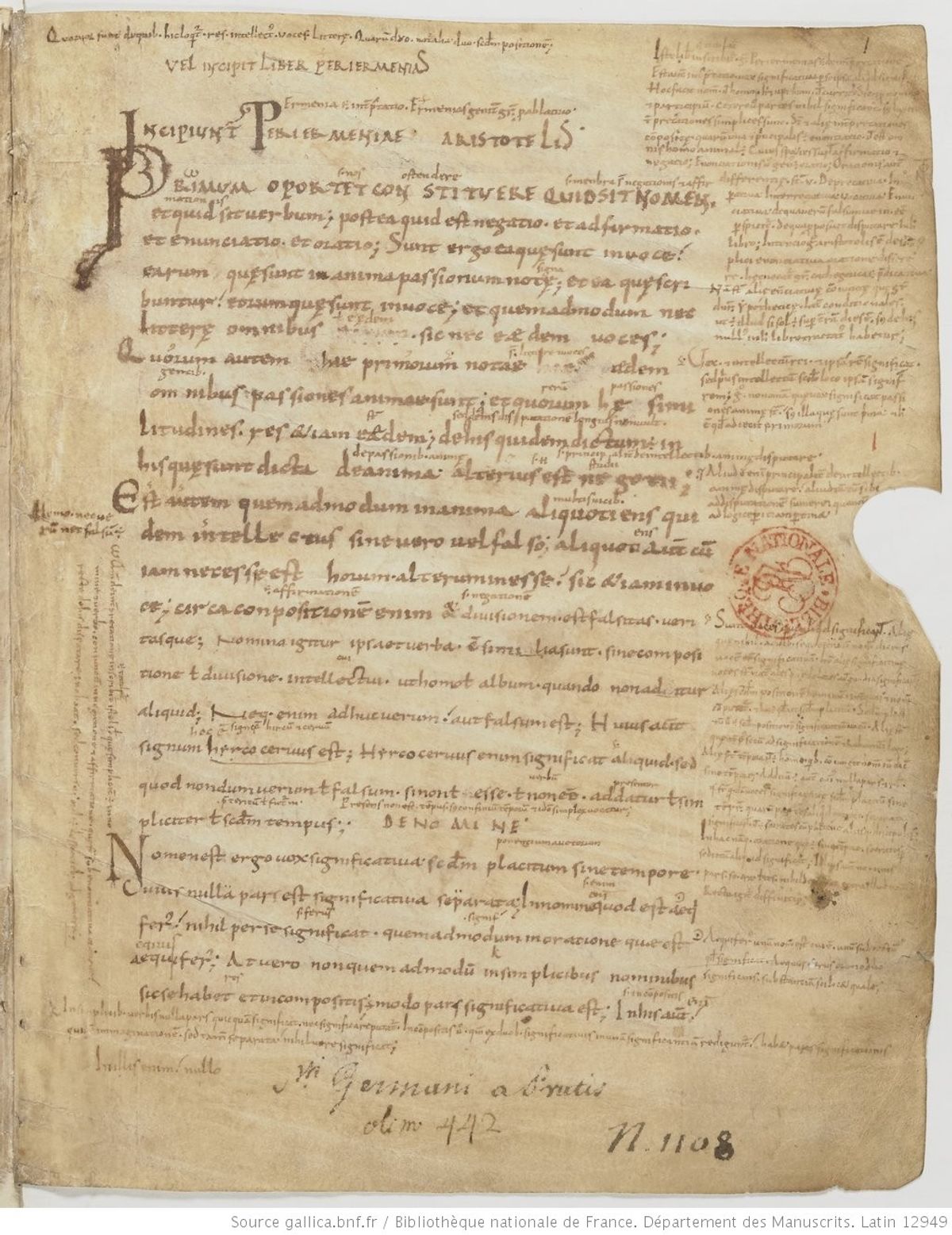

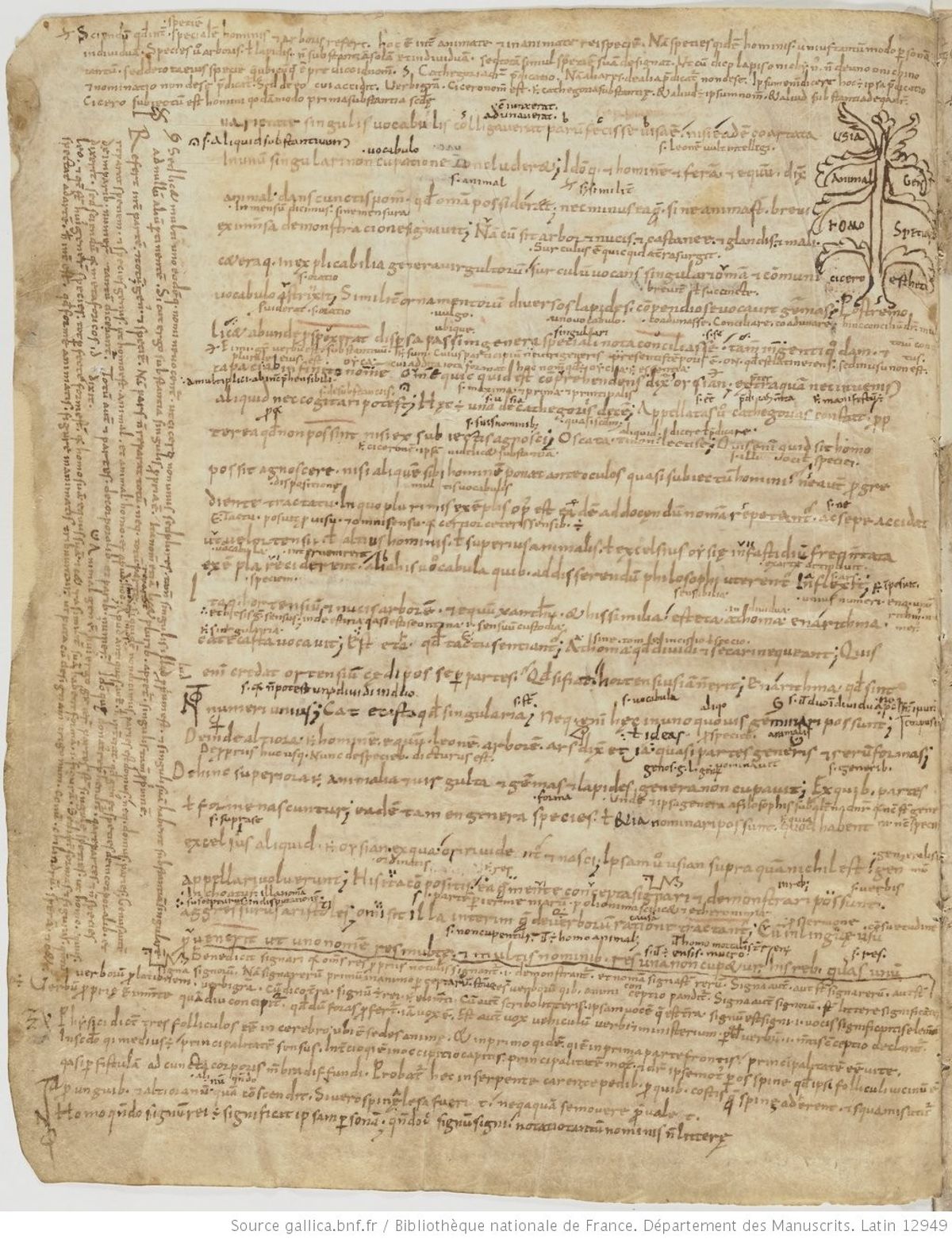

This early tenth-century manuscript of logical works displays an abundance of glosses. It is a veritable treasure trove that tells us much about the reception of logic and rational argumentation. The different users of this manuscript put much effort in creating a rich dossier of knowledge pertaining to the art of reasoning, and drew in snippets of useful knowledge from a variety of sources and traditions. The manuscript was copied in the early tenth century and belonged to the library of St-Germain in Auxerre, where it had the shelf mark N. 1108 (olim 442). The codex was restored in 1977.

https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b10542356v

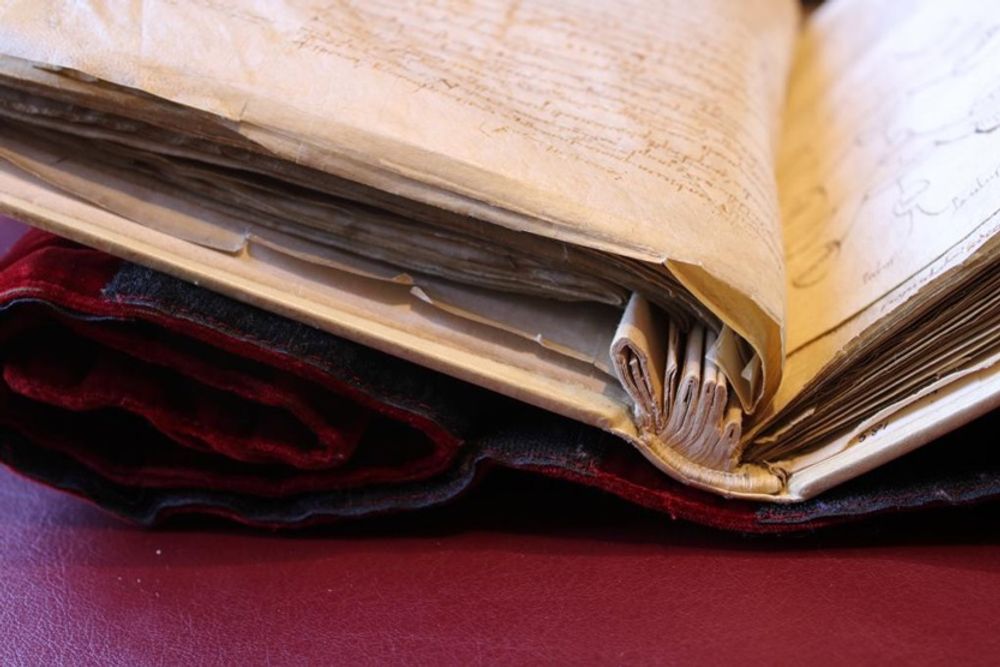

Paris, BnF, lat. 12949 is a composite manuscript consisting of six quires. As can be seen clearly in this photo, which offers a view of the tail of the codex, the quires have various dimensions. On the left, we see quires 1 to 4 (dimensions: 250-255 x 200), containing Aristotle’s Periermeneias and the Categoriae decem, on the right quires 5 and 6 (dimensions 270 x 220), containing Porphyry’s Isagoge and Boethius’ Opuscula sacra. Inserts are attached to the spine to compensate for the difference in size.

https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b10542356v

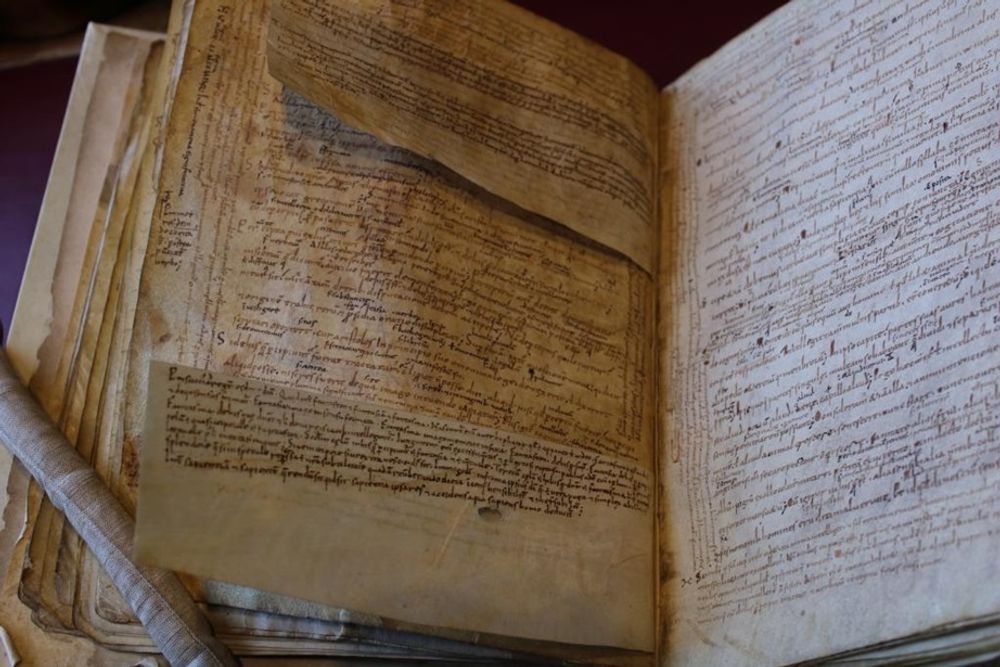

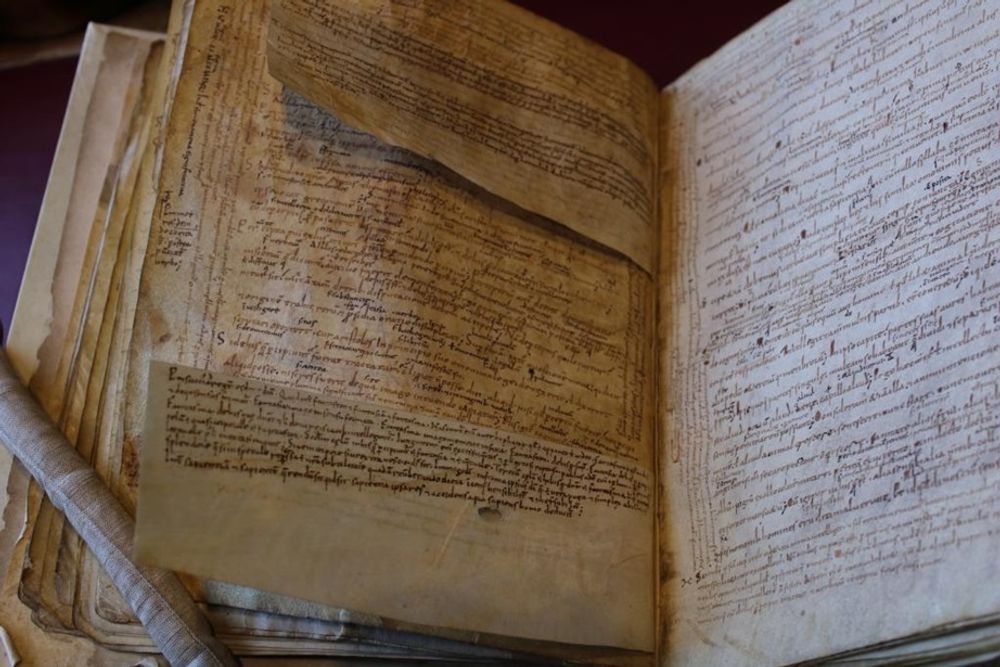

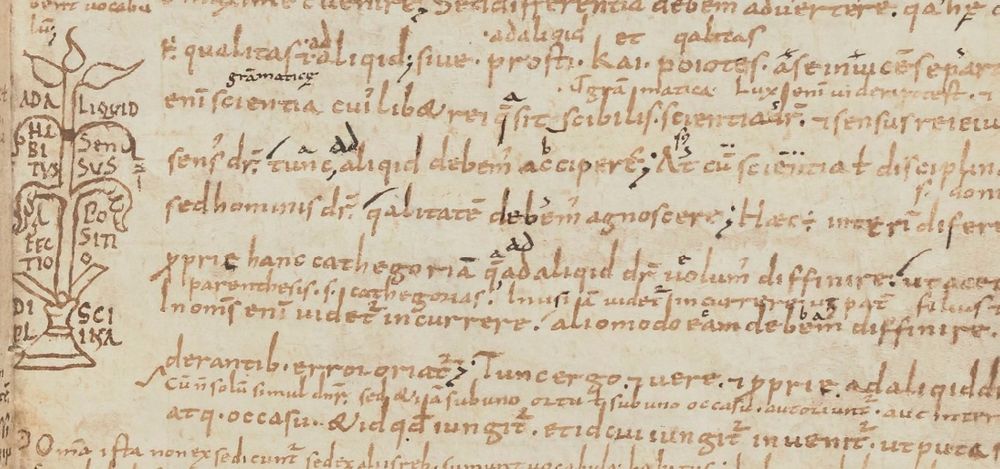

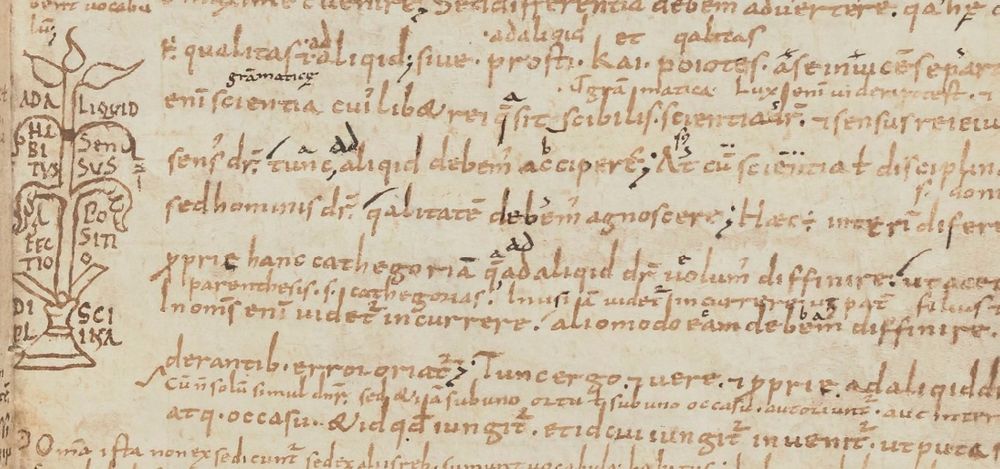

The glosses in this manuscript go back to, or can be associated with different masters: John Scottus Eriugena, Heiric of Auxerre, Israel Scotus (aka Israel the Grammarian) and a certain Aldelm who was probably also an Irish scholar.2 The manuscript is richly annotated by several hands. Some notes are contemporary to the hand of the main text, others are slightly later. Throughout the codex slips of parchment have been inserted. A remarkable feature of the layout of the glosses in this manuscript is that the notes are not only written horizontally but also vertically, across the length of the page; a very economic use of space.

https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b10542356v

The first page, with Aristotle’s On Interpretation (Peri Hermeneias) invited quite a number of annotations, but they peter out on the next pages. Aristotle’s On Interpretation deals with the relationship between language and reality. This work would receive much attention in the twelfth century, but not so much yet in the early tenth century, when this manuscript was annotated.

In the right margin is the red circular stamp of the Bibliothèque nationale.

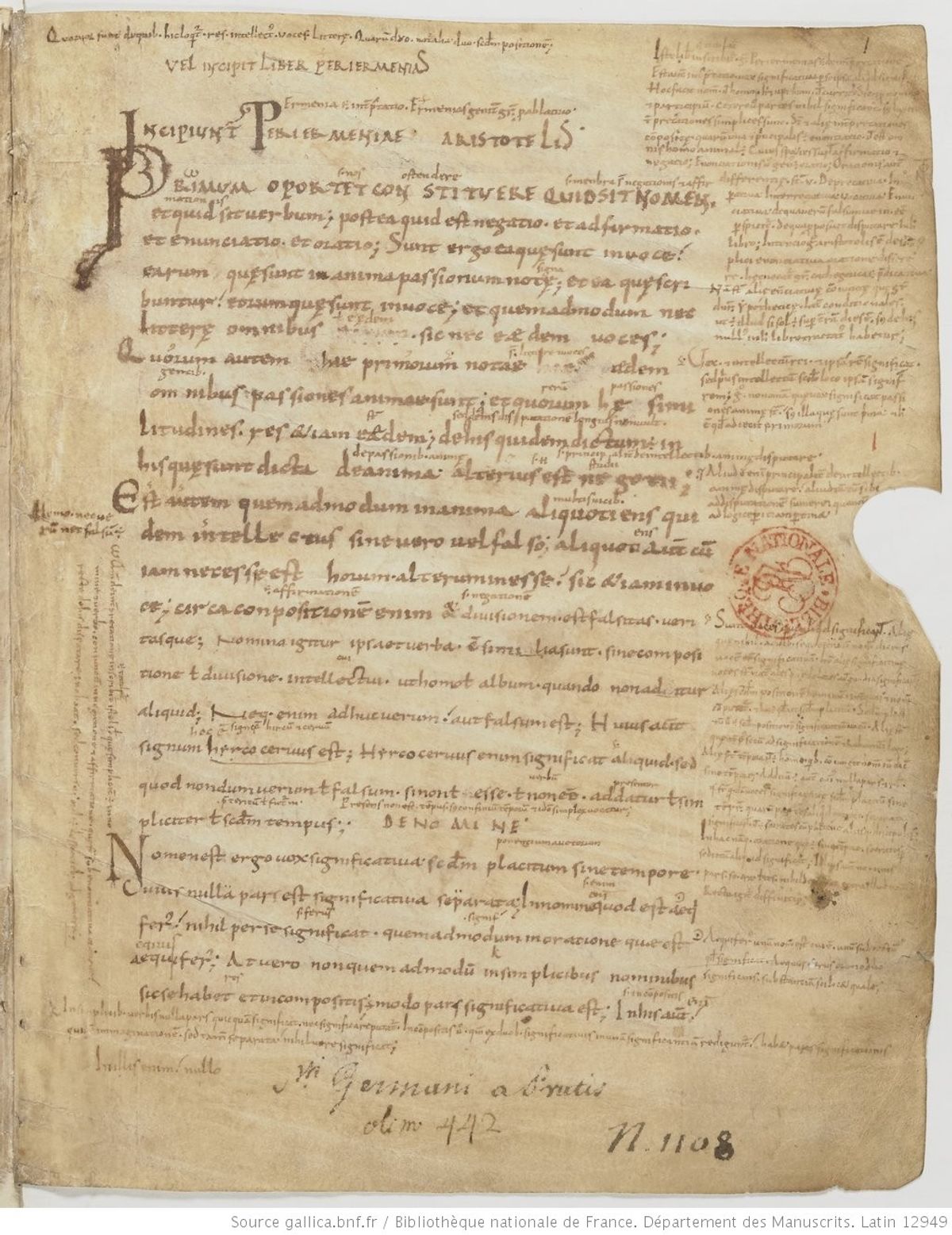

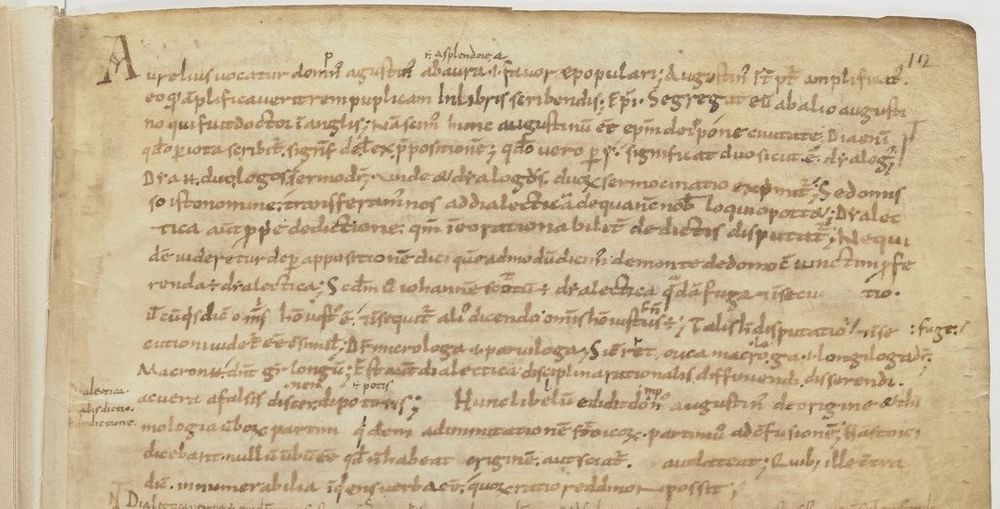

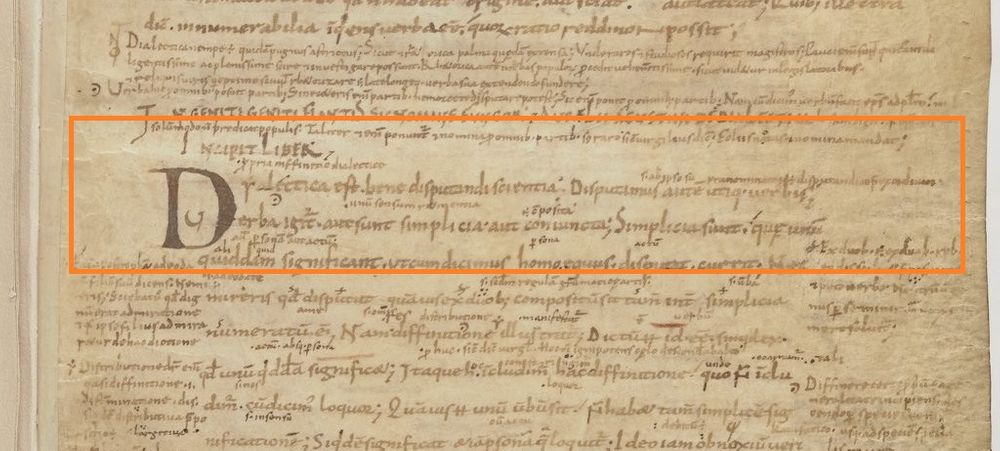

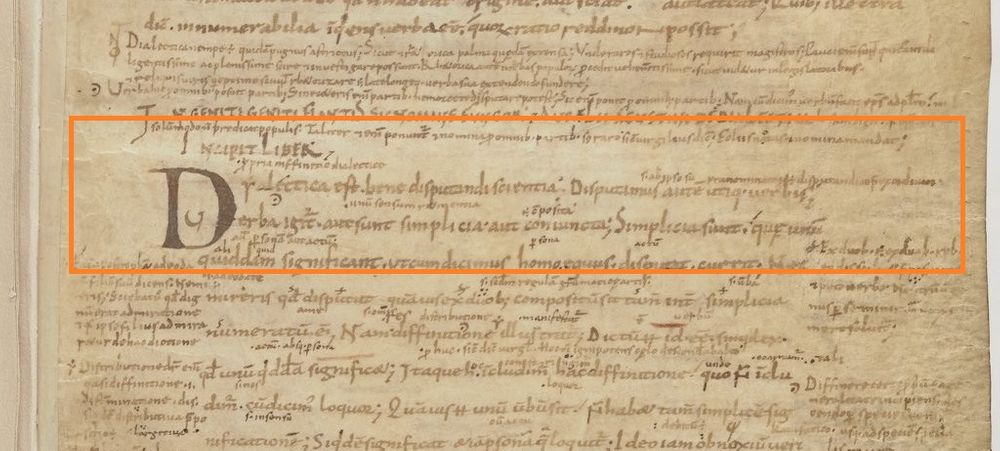

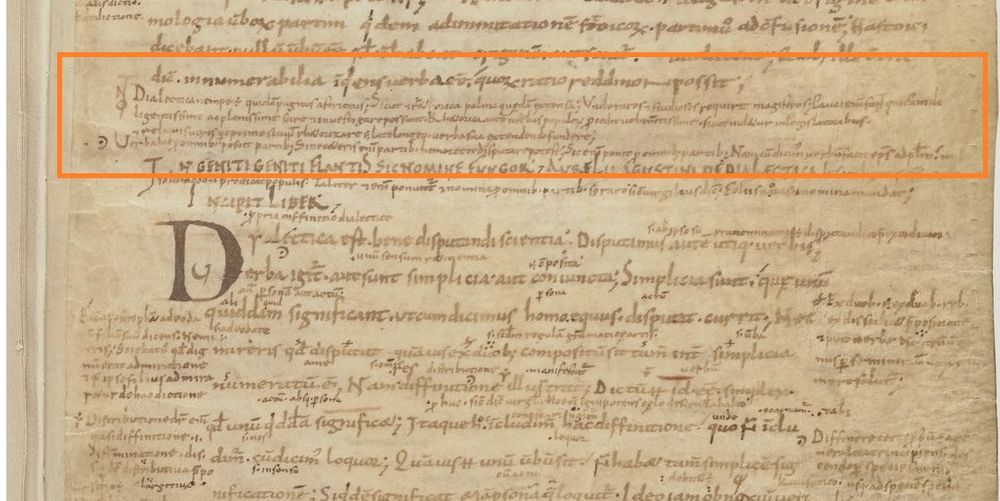

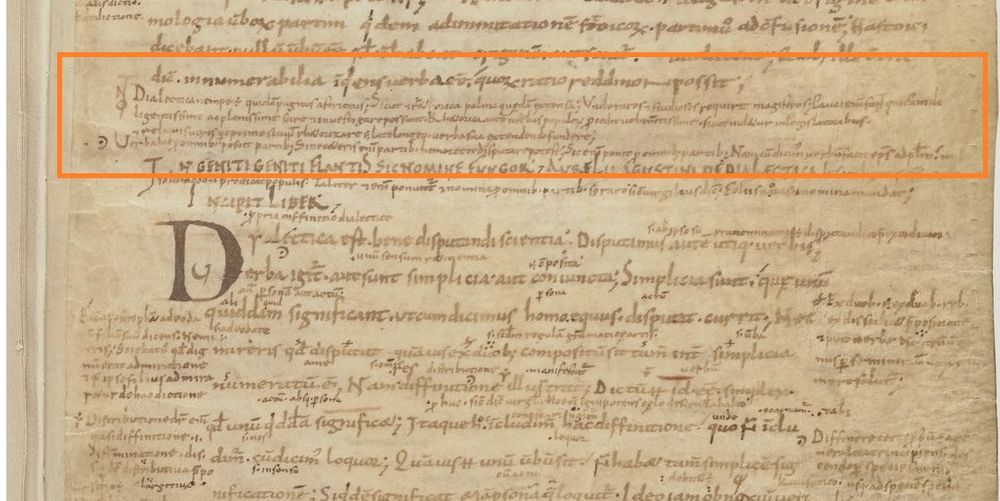

On folio 12 recto we find Augustine’s Dialectica, a brief exposition on the ambiguity of language and the etymology of words. Augustine said he never finished the Dialectica and lost his only copy of the manuscript. For this reason, Augustine’s authorship of the text has long been in doubt, but is now commonly accepted. Above is an introduction (accessus) to the author, Augustine, and an etymology of the word dialectica, with a reference to John Scottus Eriugenia.

https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b10542356v

Here (tab 1), outlined in orange, is the opening of the Dialectica proper, with the well-known opening words: “Dialectica est bene disputandi scientia” ‒ “Dialectic is the art of arguing well.” Wedged between the short introduction to Augustine and the text of the Dialectica, we encounter (tab 2) the saying attributed to the philosopher Zeno: “Rhetoric is an open hand, dialectic a clenched fist.”3 It is part of a longer quotation, taken from Alcuin’s De dialectica, in which Alcuin stated that devoted teachers of dialectic are rare, and that only few are able to fully understand it and investigate it properly.

https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b10542356v

https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b10542356v

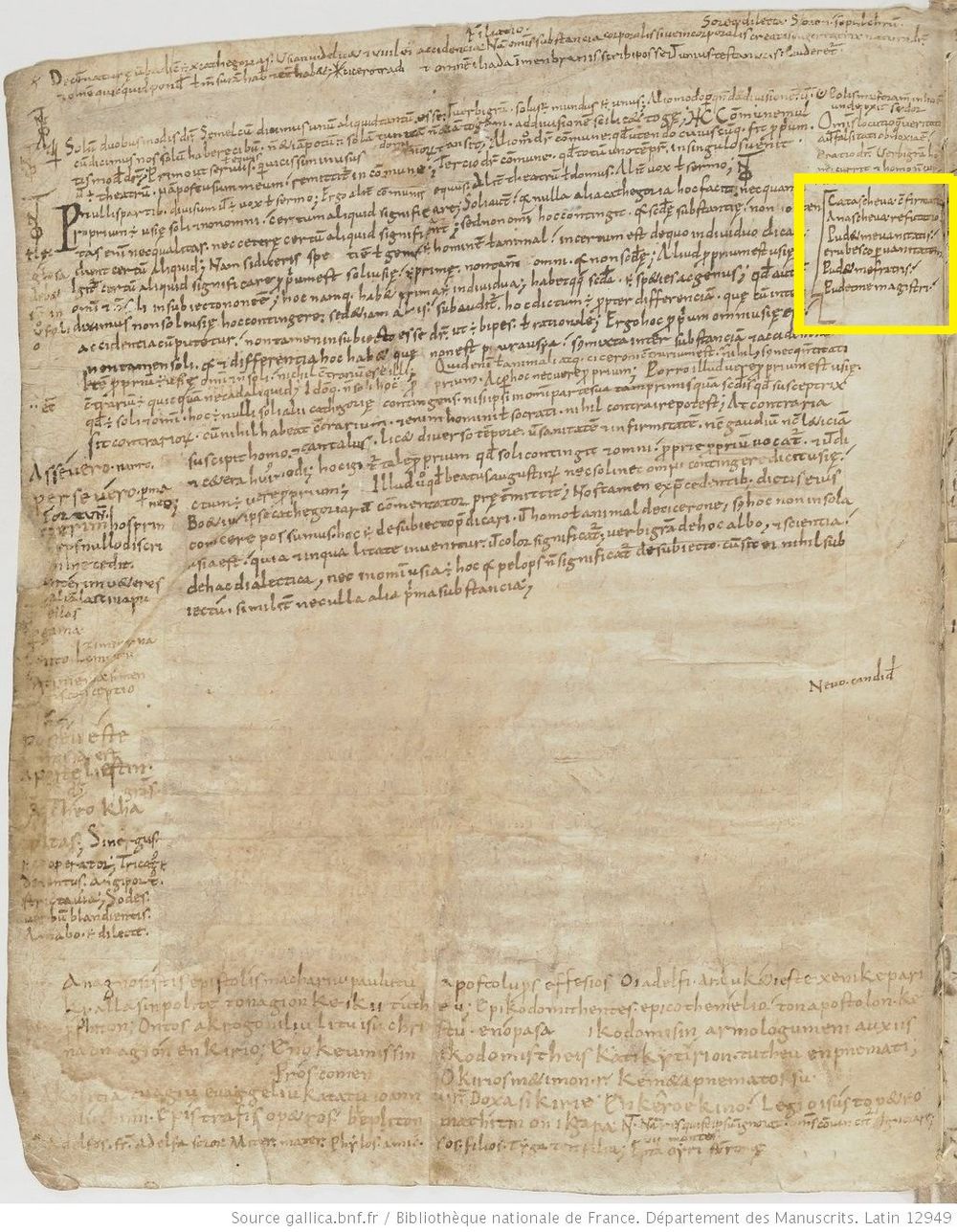

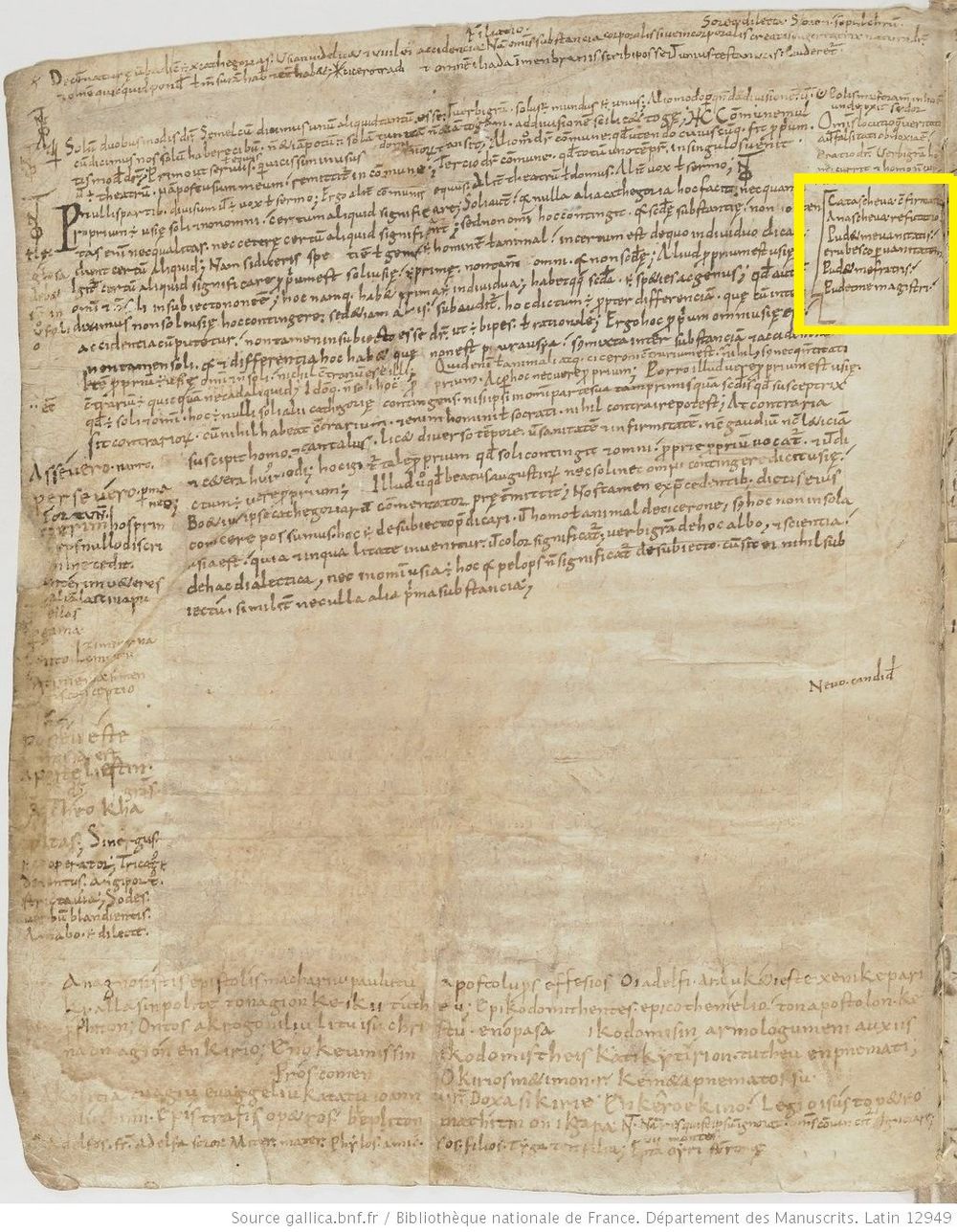

On folio 23 verso, in the margin of a fragment of an unidentified text that discusses ousia, essence or substance, a memory aid has been added to help the reader remember the distinction between catascheva (confirmation) and anascheva (refutation):

Catascheva confirmatio

Catascheva confirmation

Anascheva refutatio

Anascheva refutation

Pudet me vanitatis

I am ashamed of my empty pride

erubesco per vanitatem

I blush because of empty pride

Pudet me fratris

I am ashamed of my brother

Pudet me magistri

I am ashamed of my master

https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b10542356v

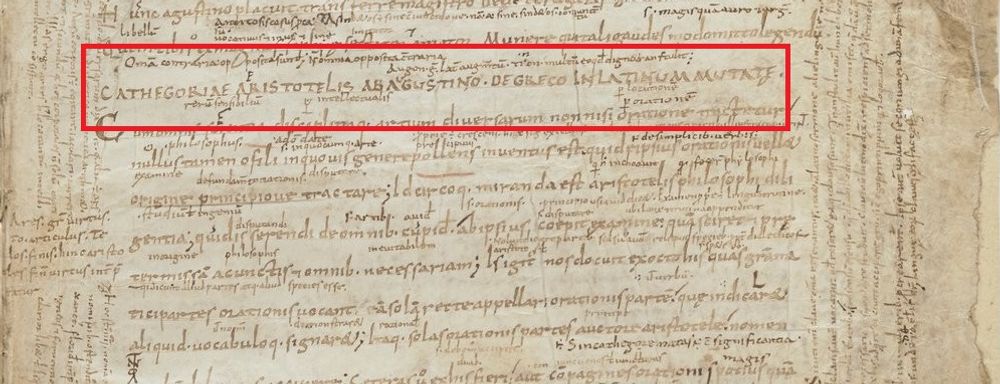

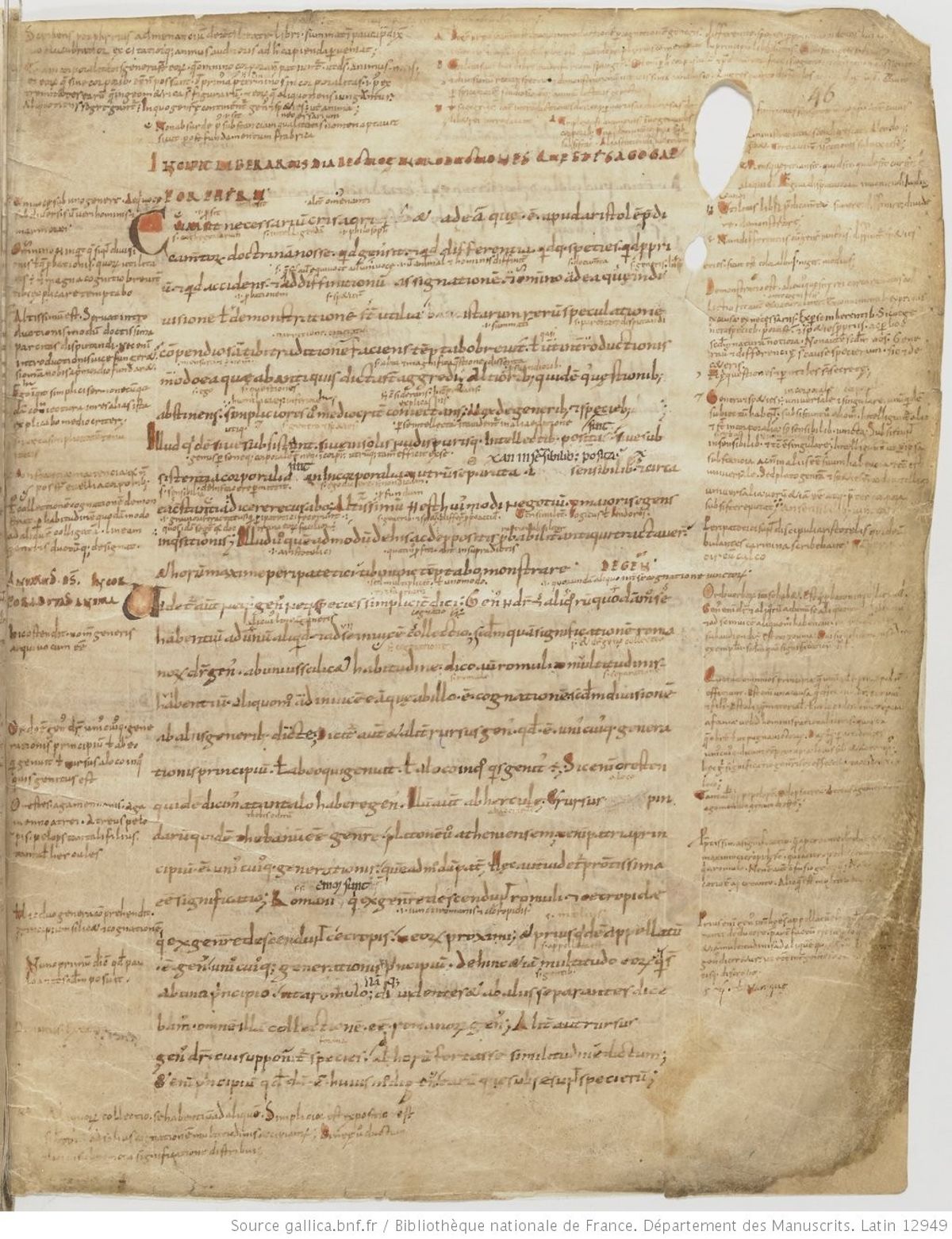

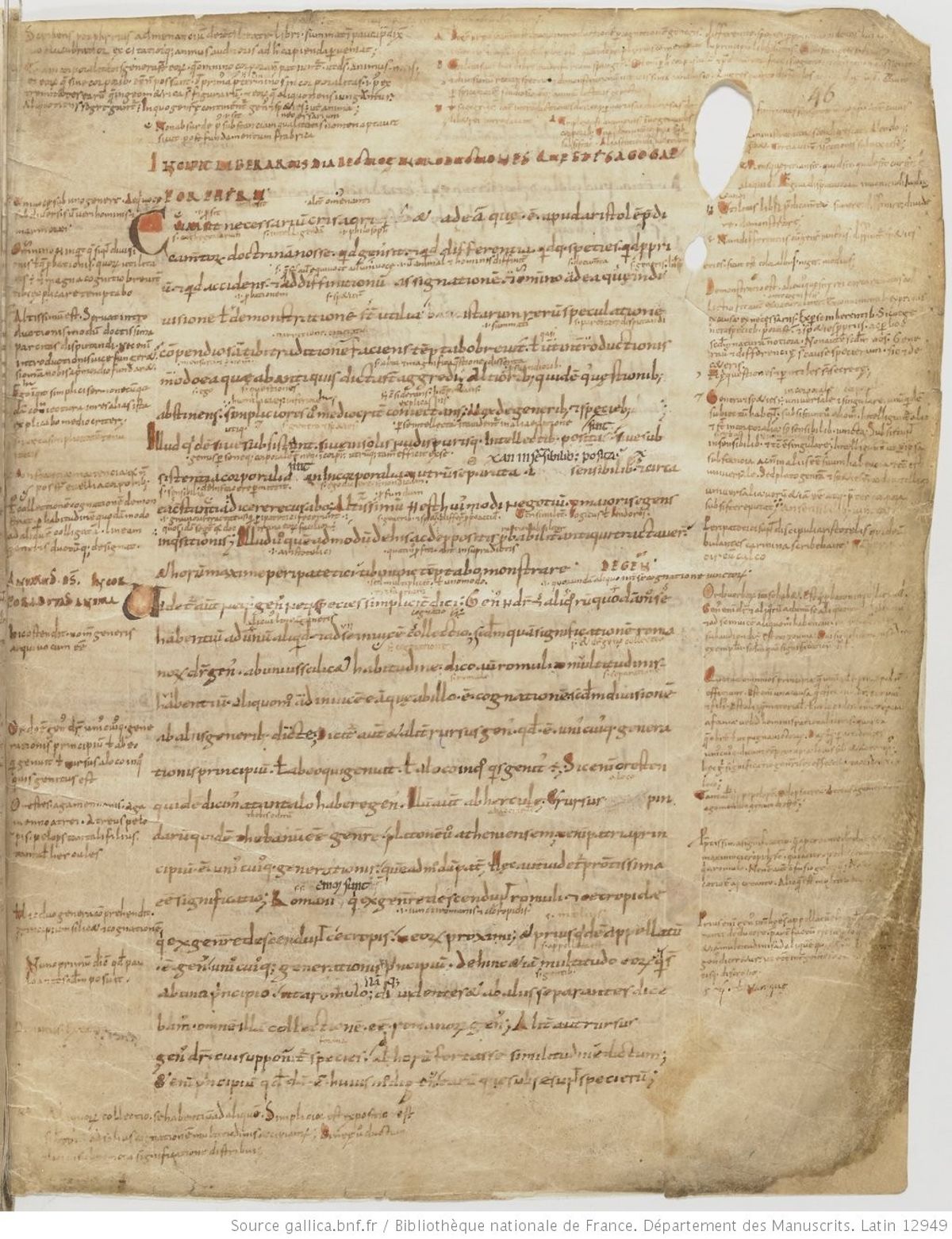

On folio 24 recto is the opening of the Categoriae decem ‒ Ten Categories, also known as the Paraphrasis Themistiana. The title reads: “The Categories of Aristotle translated by Augustine from Greek into Latin.”4 This text was ascribed to Augustine in the early middle ages. From the eighth to eleventh century the Categoriae decem drew by far the most attention of scholars and students interested in logic. This interest is also evident from the many annotations the text received in this early tenth-century manuscript.

https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b10542356v

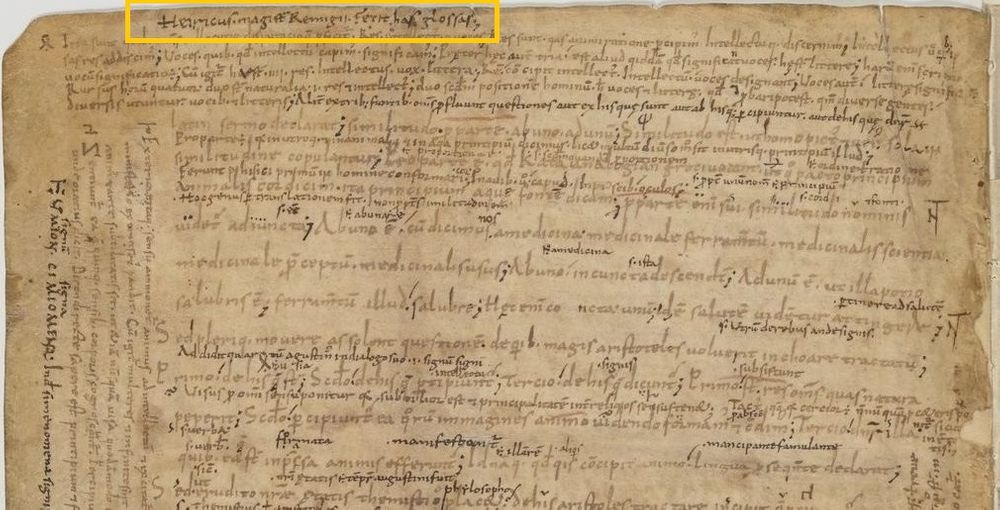

According to an annotation on folio 25 verso the glosses (or one strand of them) go back to Heiric of Auxerre (d. 876), a student of Lupus of Ferrières and teacher of Remigius and Hucbald. The annotation reads: “Heiricus magister Remigii fecit has glossas” – “Heiric the master of Remigius made these glosses.”

https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b10542356v

The glosses to the Categoriae decem in this manuscript are partly standard glosses that can be found in many manuscripts of this text, but there is also a strand of glosses (perhaps the ones that are here attributed to Heiric?) that go back to ideas expressed by John Scottus Eriugena, in particular in his Periphyseon. John Marenbon, who did not think much of the intellectual rigour of these annotations characterized them as follows: “Many of the Eriugenian glosses seem to be the product of someone whose mind is well stocked with motifs and phrases from the Periphyseon who has set about the task of commenting the Ten Categories after a pint too many.”5

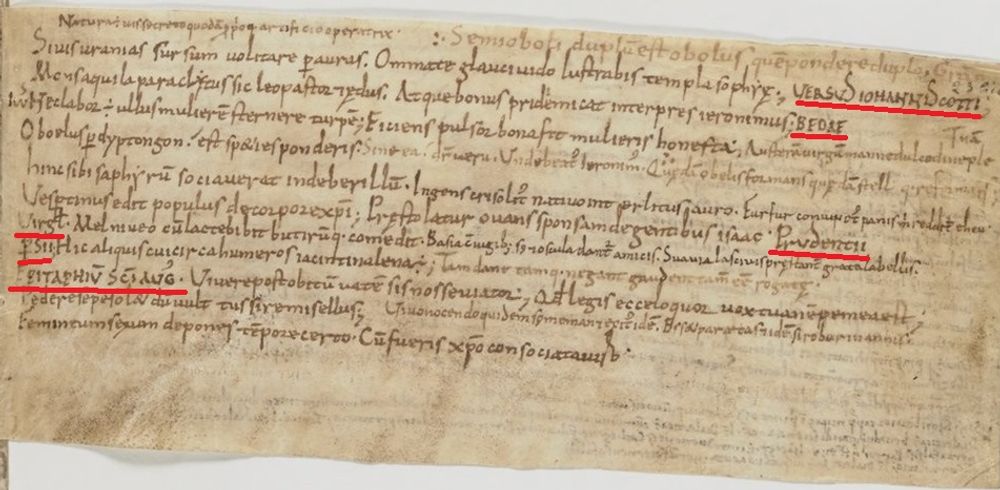

On a slip of parchment inserted between folio 23 verso and folio 24 recto we find verses of John Scottus Eriugena, Bede, Prudentius, Virgil and Persius and an epitaph of Augustine, alongside various anonymous verses and statements. The quotations bear no direct relationship to any of the texts in this codex, apart from the recurrence of familiar names. Perhaps the notes were made by a student, scholar or master for personal use and recollection on a scrap of parchment that travelled with this manuscript and was at some point inserted into the codex. In the image we underlined in red: “versus Iohanni Scotti”, “Bedae”, “Virgilii”, “Prudentii”, “Persii”, “epitaphium Sancti Augustini”. The epitaphium reads: “Passerby, do you wish to know how poets still live after death? Those words you read, behold I speak. Your voice is very much mine.”6

https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b10542356v

The glosses to Porphyry’s Isagoge, starting on folio 46 recto, consist mainly of excerpts from Boethius’s commentaries, Isidore of Seville, Alcuin’s De dialectica and Macrobius Commentary on the Dream of Scipio.

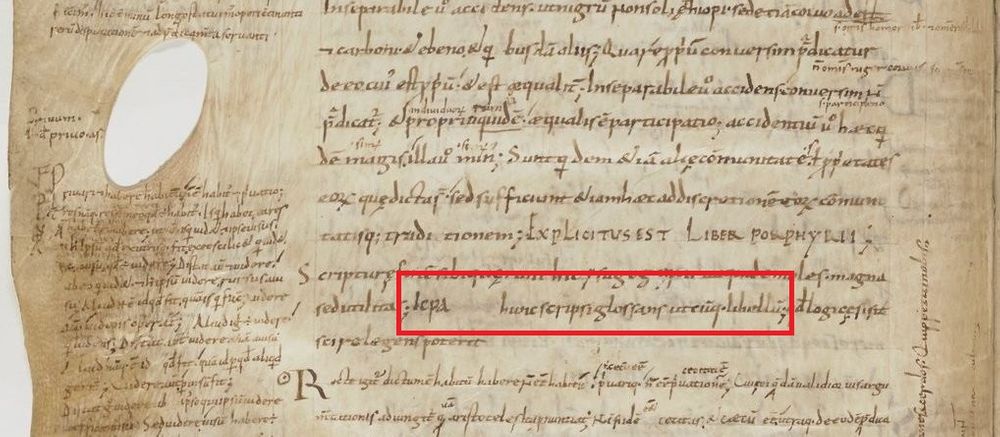

On folio 52 verso we find this attribution (outlined in red): “I, Icpa, wrote this little book, glossing it in some way” (“Icpa [rasura] hunc scripsi glossans utcunque libellum”. Édouard Jeanneau has proposed that ‘Icpa’ is the Latin transliteration of the Greek capital letters ΙΞΡΑ (ISRA) and refers to Israel the Grammarian (c. 895 – c. 965).

https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b10542356v

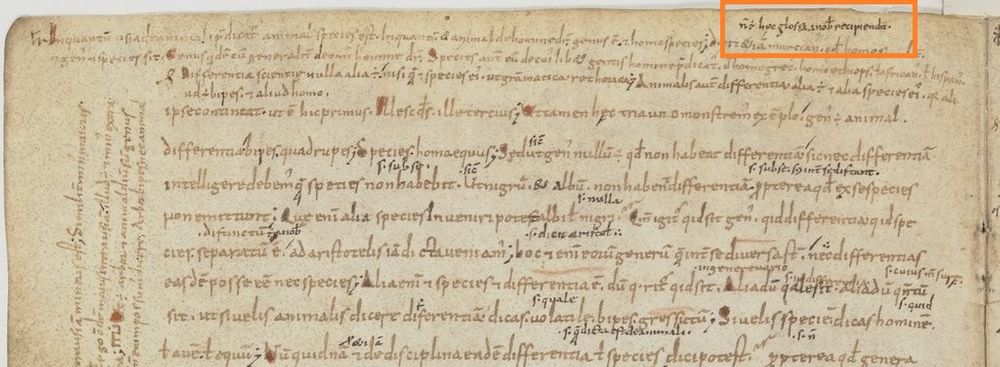

On folio 27 verso we encounter a note of criticism attached to a gloss. Written above a discussion in a gloss of ‘man’ being both ‘genus’ and ‘species’, with ‘genus’ referring to man in general and – according to Martianus, the gloss says – ‘species’ to particular people, such as Ethiopians, Africans and Romans, a note written in darker ink states: ‘Non est haec glossa a nobis recipienda’ – ‘We should not accept this gloss’.

https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b10542356v

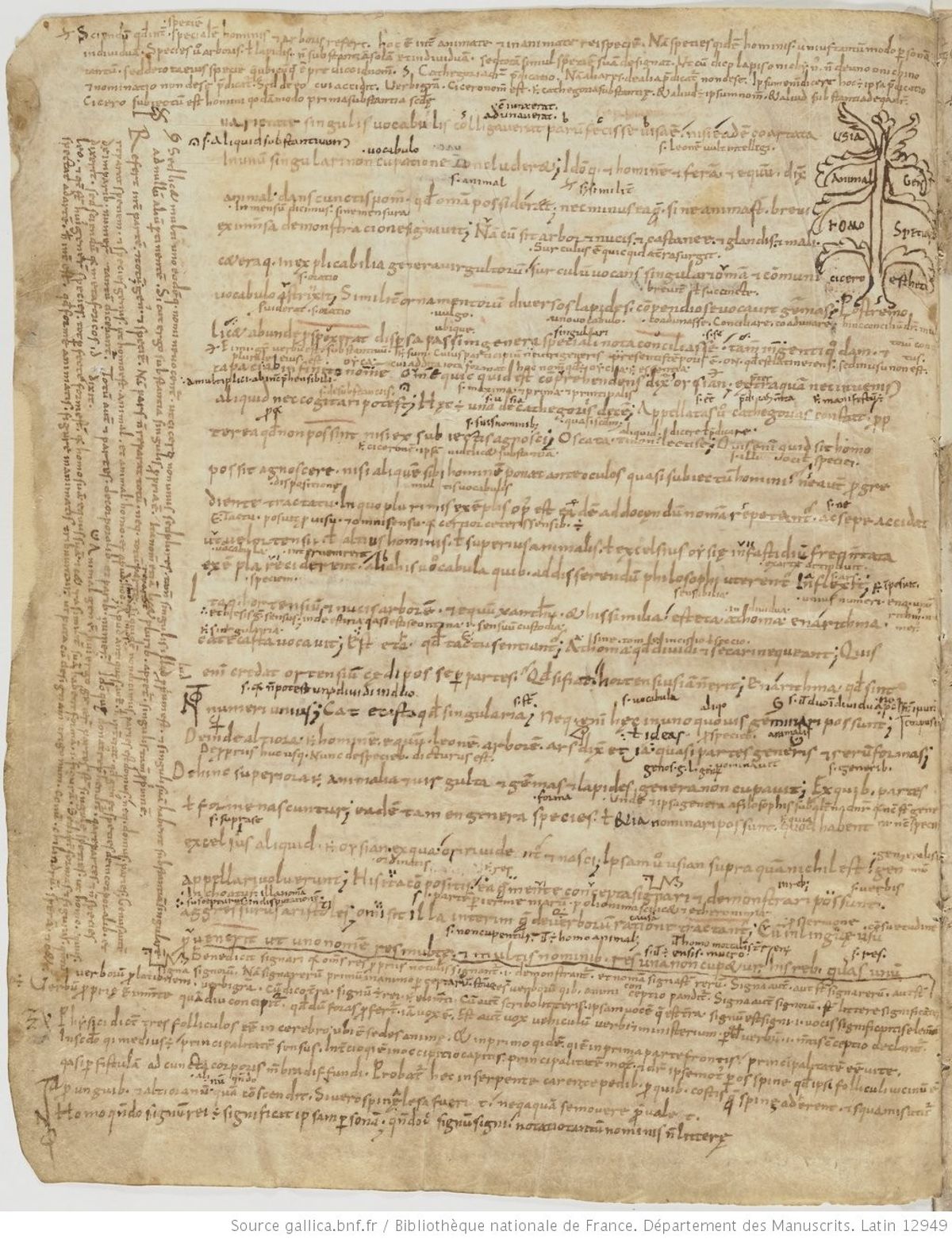

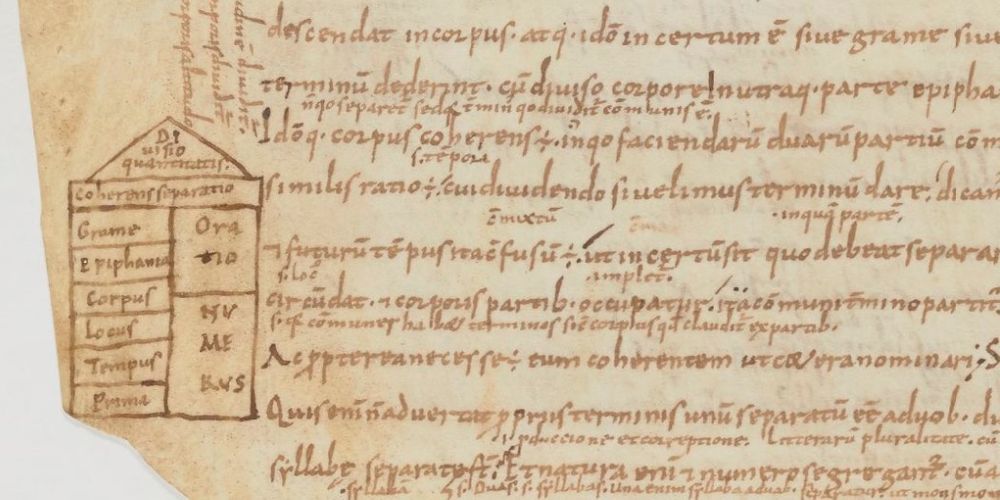

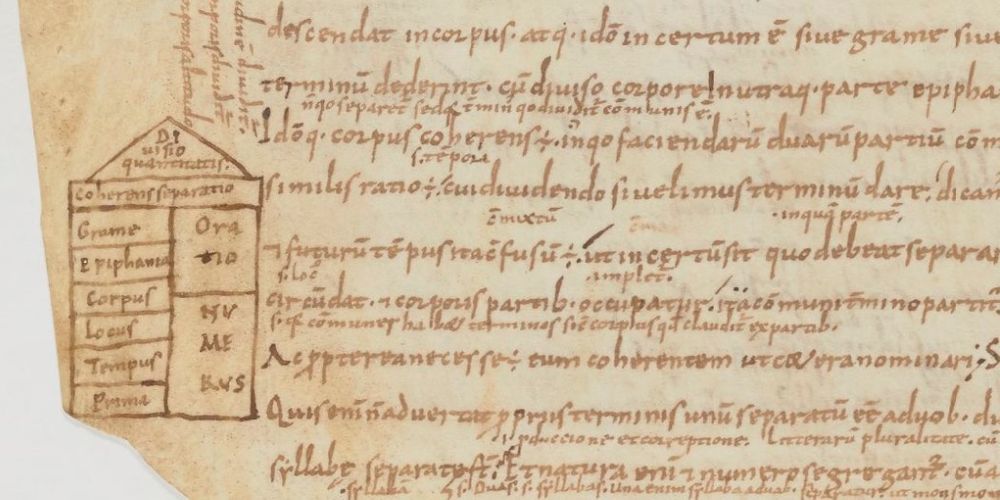

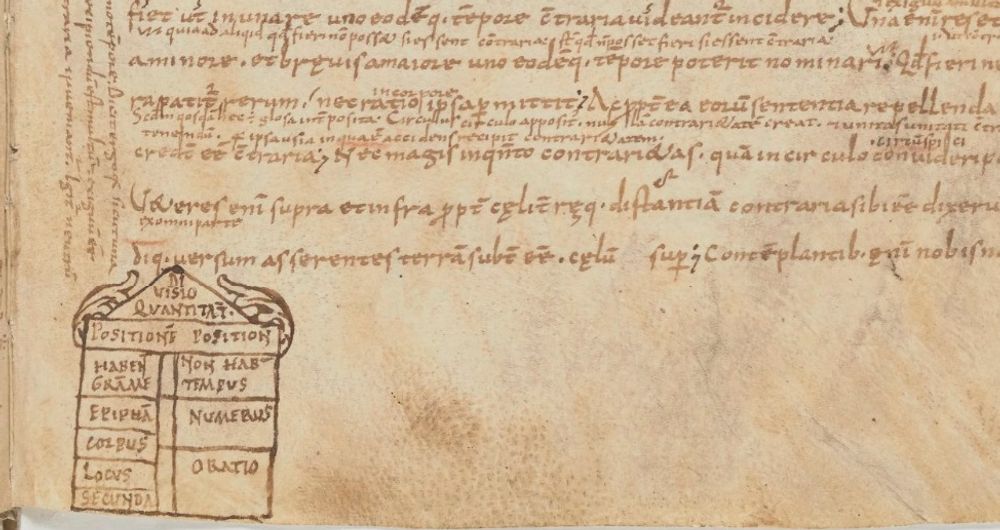

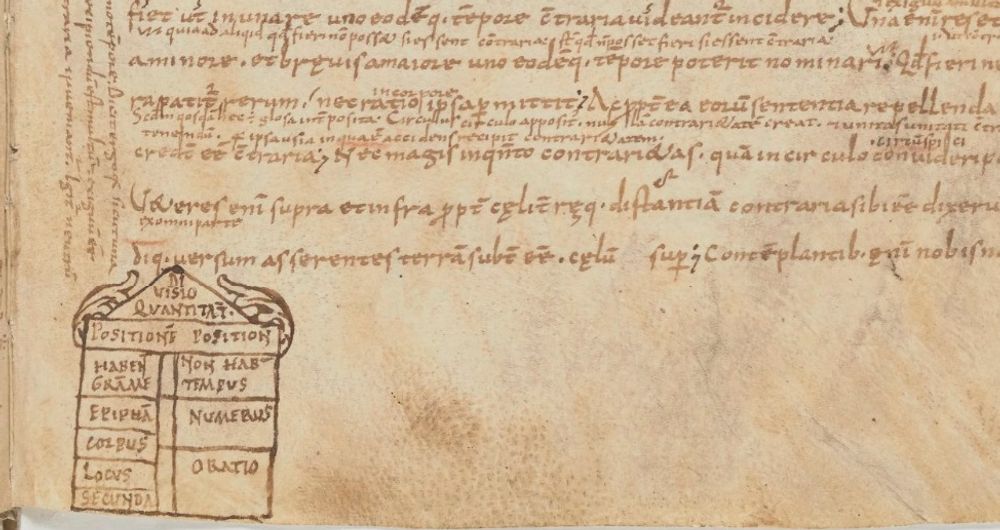

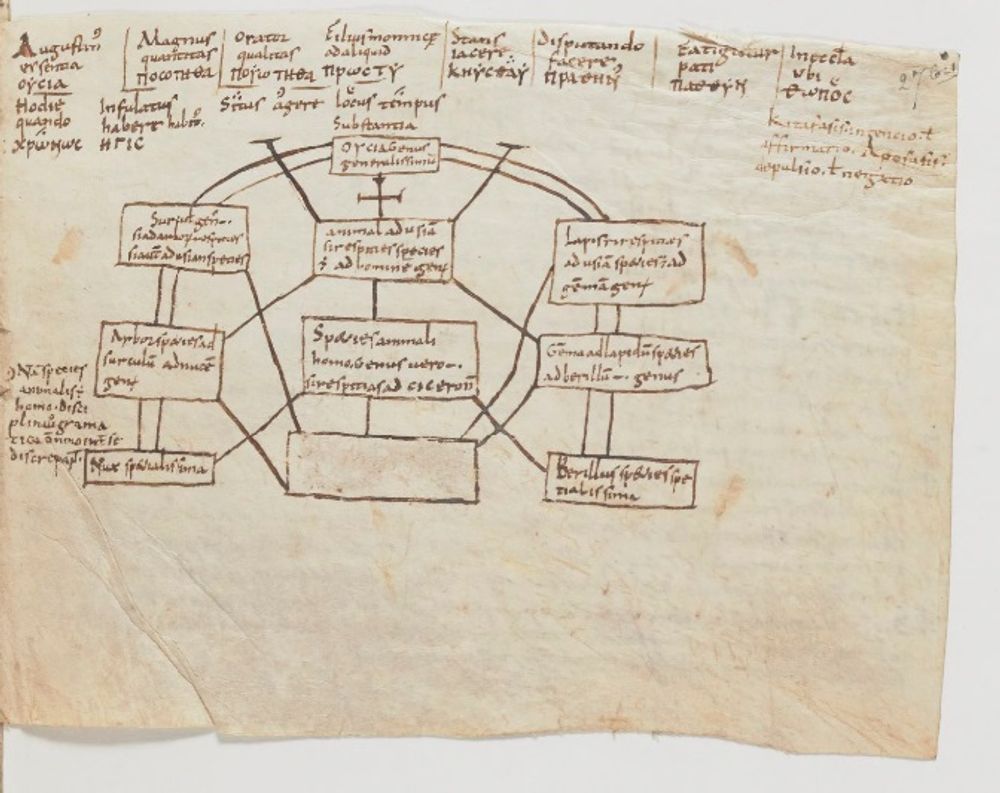

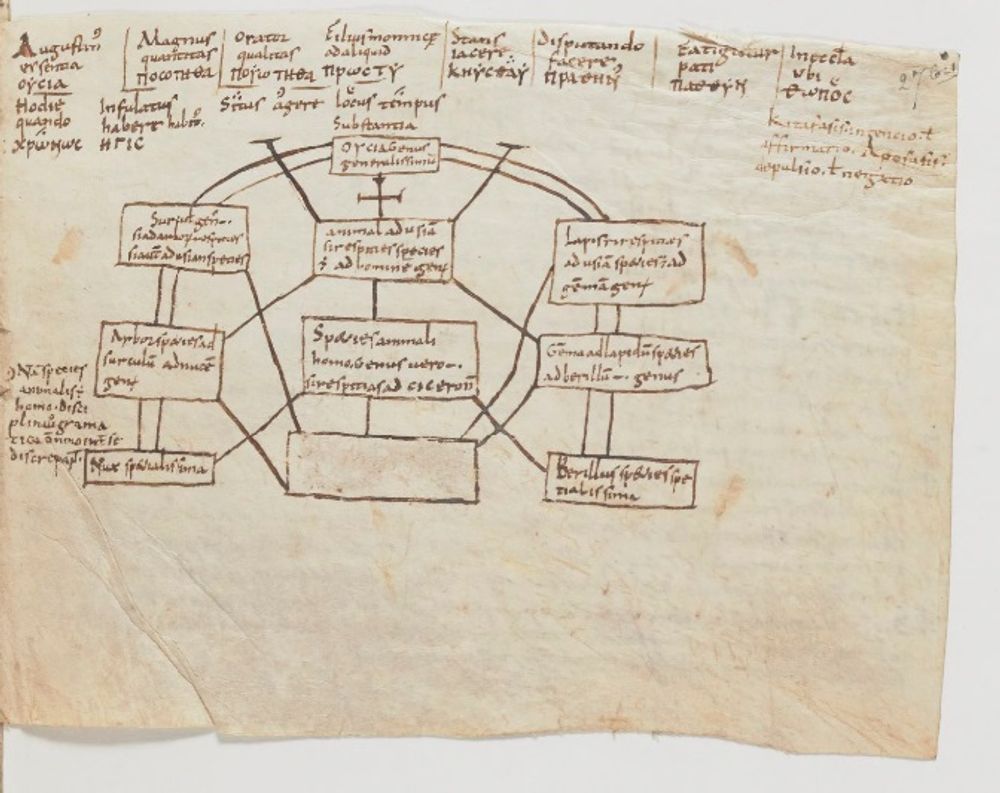

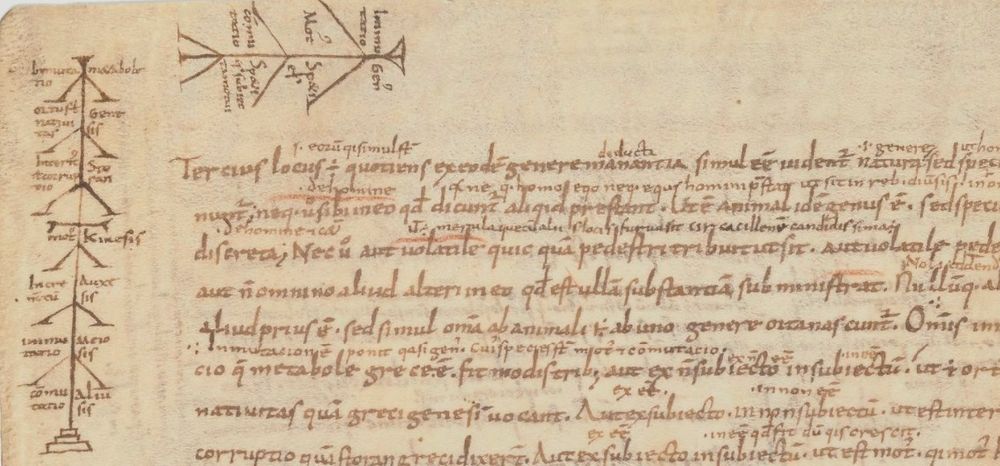

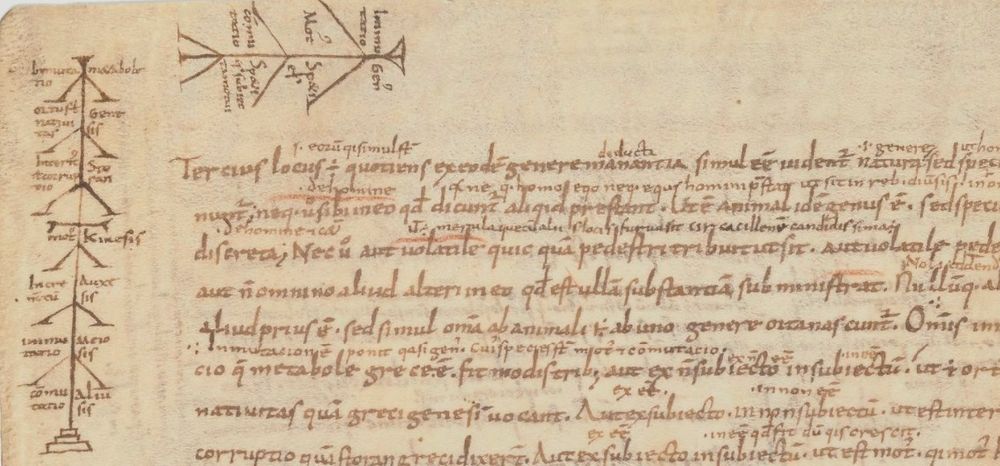

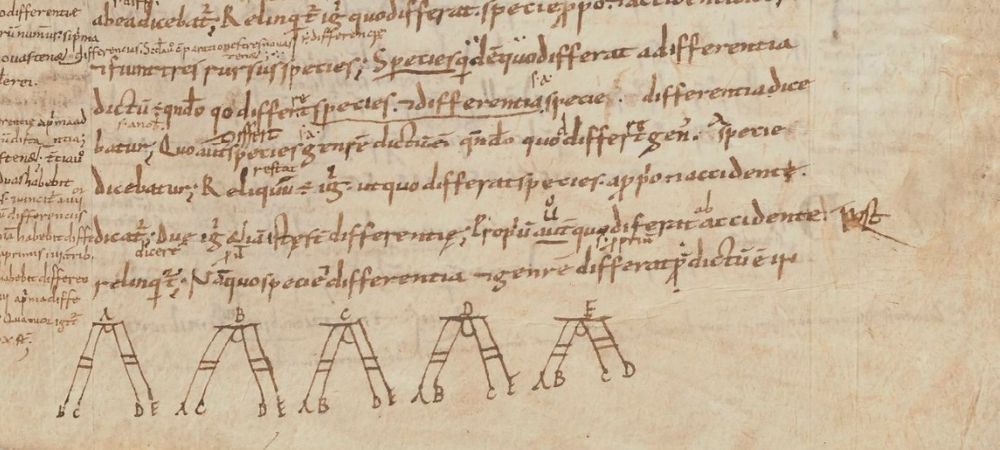

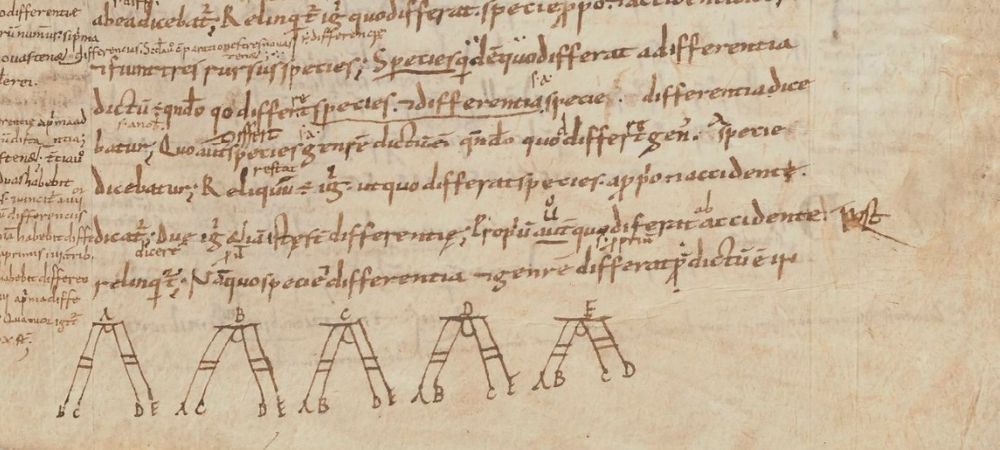

Throughout the codex a number of diagrams are found in a variety of shapes: trees, houses, fishbones. They illustrate the habit of medieval scholars to organize, understand and memorize the knowledge they encountered in the text.

https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b10542356v

https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b10542356v

https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b10542356v

https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b10542356v

https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b10542356v

https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b10542356v

Sources used for this contribution:

- John Contreni, ‘The Irish ‘colony’ at Laon during the time of John Scottus’, in René Roques (ed.), Jean Scot Erigène et l’histoire de philosophie (Paris, 1977), pp, 59-67.

- Édouard Jeaunneau, ‘Pour le dossier d’Israël Scot’, Archives d’histoire doctrinale et littéraire du Moyen Age 52 (1985), pp. 7-72

- John Marenbon, From the Circle of Alcuin to the school of Auxerre. Logic, theology and philosophy in the early Middle Ages (Cambrdige, 1981)

- John Marenbon, ‘Logic before 1100: The Latin Tradition’, in Dov. M. Gabbay, J. Woods (eds.), Handbook of the History of Logic 2, (Amsterdam, Elsevier, 2008), p. 1-64.

Contribution by Irene van Renswoude. I thank Janneke Raaijmakers for her critical reading and always excellent suggestions for my contributions.

Cite as, Irene van Renswoude, “Paris, BnF, lat. 12949”, The art of reasoning in medieval manuscripts (Dec 2020), https://art-of-reasoning.huygens.knaw.nl/lat12949. ↑

Contreni, 1977. ↑

“Nota. Dialectica nempe est quidam pugnus astrictus; Sicut et rhetorica palma quedam extensa; Unde raros et studiosos requirit magistros; Pauci enim sunt qui eam diligentissime ac plenissime scire et investigare possunt.” ↑

CATHEGORIAE ARISTOTELIS AB AUGUSTINO DE GRECO IN LATINUM MUTATE ↑

Marenbon, 2008, 35. ↑

“Vivere post obitus vatem vis nosse viator? Quod legis, ecce loquor, vox tua nempe mea est” Possidius, Vita Augustini, 3.18. ↑