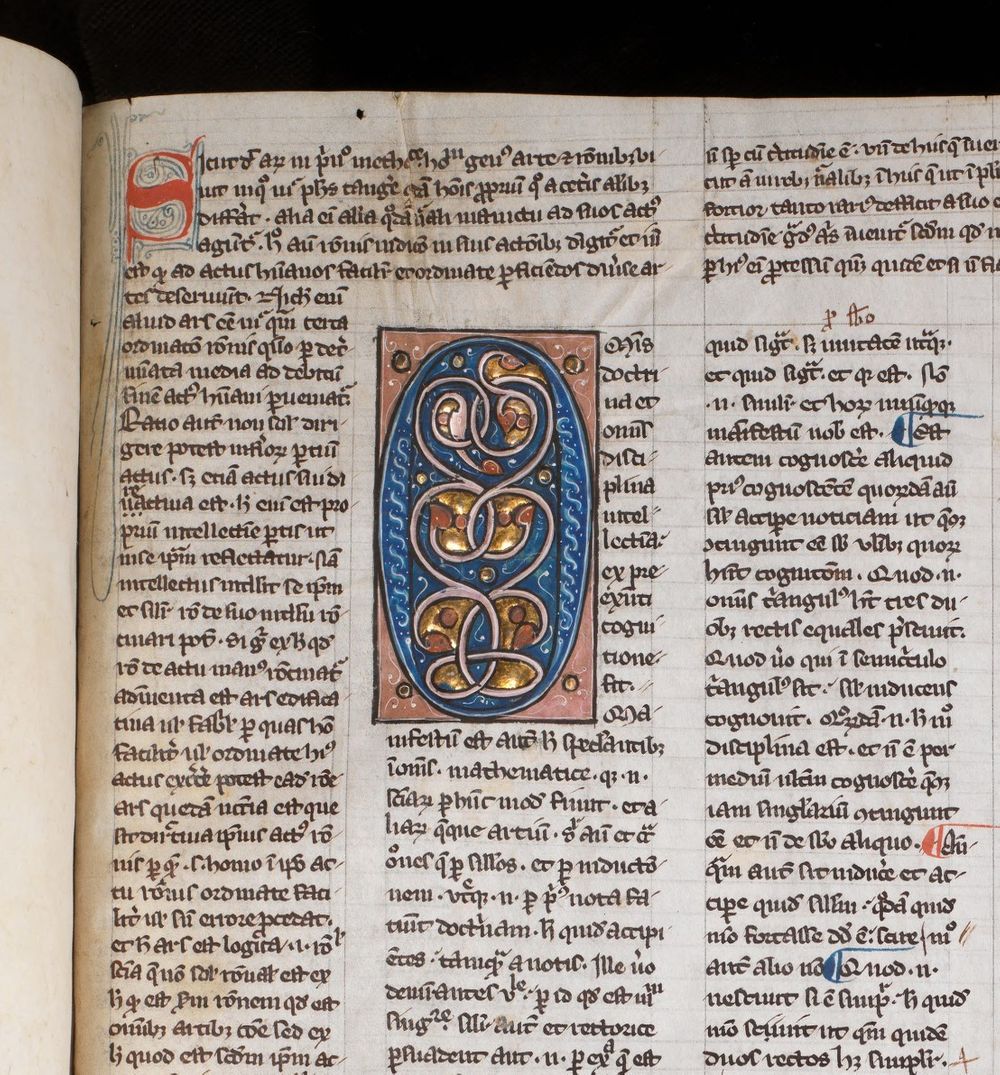

Apuleius was a Platonist philosopher and rhetorician active in the second century CE. Born in Madaura, in the Roman province Africa, he was educated at Carthage and Athens, and taught rhetoric in Rome before returning to Africa. He is an exponent of the period known as the Second Sophistic, an age of cultural flowering characterized by a revived interest in the study of ancient Greek rhetoric and philosophy. The Peri hermeneias (also known as De interpretatione or ‘On Interpretation’) is a short handbook of formal logic that deals with the Aristotelian logical doctrine. It has a Greek title, but is, in fact, the earliest Latin logical treatise that is known. The text is an exposition of categorical logic, which uses simple categorical propositions (such as ‘all men are mortal’) to deduce necessary conclusions. The principal subject of the text is the relation between subjects, predicates and propositions, as well as a classification of the various types of propositions. The work includes the Aristotelian square of opposition in order to describe how different propositions relate to each other. It was important for the transmission of Greek logical thought to the medieval Latin West and for the Latinisation of Greek technical terms. Apuleius made a fair amount of logical theory available to medieval readers. The Peri hermeneias served as an aid, together with Boethius’ commentaries, to understand the logical texts of Aristotle.

http://initiale.irht.cnrs.fr/decor/53658

Source used for this contribution:

Bobzien, Susanne, "Ancient Logic", The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Summer 2020 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.), URL = <https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/sum2020/entries/logic-ancient/>.

Contribution by Katia Riccardo.

Cite as, Katia Riccardo, “Text portaits”, The art of reasoning in medieval manuscripts (Dec 2020), https://art-of-reasoning.huygens.knaw.nl/text-portraits. ↑

Aristotles’ Categoriae (“Categories”) and De interpretatione (“On interpretation”) constituted the central texts for the study of logic throughout the Middle Ages. The Categories and On interpretation were part of the Organon (“instrument”), the collection of Aristotle’s six logical works. For Aristotle logic is the instrument through which it is possible to come to an understanding of all things.

The word “category” means “predication”, the phenomenon that we can use words to express a truth about something else, for example: “Socrates is human”, or “Horses are animals”. The purpose of the categories was to create a system that could be used to describe everything in the world. Aristotle describes ten of these categories.

The Aristotelian categories can be considered as ten different kind of predicates or ways in which a predicate can be related to its subject. Predicates are terms that can only be universal: in “Socrates is human”, the predicate is the property of being human; in “horses are animals”, the predicate is the property of being an animal, etc. The ten categories, combined, can provide an explanation of what any individual thing is. On interpretation primarily deals with analyses of the basic elements of language and the nature of truth and falsehood. Its main concern is to discuss the relations of compatibility and incompatibility between propositions. A proposition is the most basic statement, a sentence that is complete and asserts something (e.g. Socrates is wise). The square of opposition was devised for examining the relation between different propositions.

http://initiale.irht.cnrs.fr/codex/7213/9729

Until the twelfth century, when more of the Aristotelian Corpus was made available in Latin because of a new influx of texts from the Greek and Arabic world, these works were known and circulated mainly in the Latin translations and commentaries written by Boethius. Boethius was the channel through which Greek philosophical ideas were transmitted into the Latin tradition, and his commentaries on the Categories and On interpretation, together with Porphyry’s Isagoge, became a standard part of the logical curriculum. These texts were known as the logica vetus.

Sources used for this contribution:

Contribution by Katia Riccardo.

Cite as, Katia Riccardo, “Text portaits”, The art of reasoning in medieval manuscripts (Dec 2020), https://art-of-reasoning.huygens.knaw.nl/text-portraits. ↑

The Organon (“Instrument”) is the collection of Aristotle’s logical treatises. The works that deal with argumentation are the Prior and Posterior Analytics, Topics and Sophistical Refutations. The Prior Analytics contain the doctrine of the syllogism, which is, in essence, a logical argument made up of three parts: two premises and a conclusion (if all men are mortal, and if Socrates is a man, then Socrates is mortal). In the Posterior Analytics Aristotle applied the theory of syllogism to reach “scientific demonstration”, to establish scientific truths. This work was not among the Aristotelian works that Boethius translated into Latin and came to the West in the twelfth century.

https://www.e-codices.unifr.ch/en/list/one/ubb/F-I-0001

The Topica demonstrates how to construct arguments. It lists some hundred topoi: for example, if a predicate is generally true of a genus (e.g. living things), then the predicate is also true of any species (e.g. plants) of that genus. Thus: “if the capacity of nutrition belongs to all living things, then the capacity of nutrition belongs to plants”, since plants are living things. They are useful to construct dialectical arguments, and with them the dialectician should be able to formulate deductions on any problem he could be proposed. The aim of the Topics was to teach the questioner and the answerer how to sustain their parts in a dialectical discussion (a debate or disputation); they were described by Aristotle as the starting point for attacking the theses of the opponents.

The Sophistical Refutations, considered as the final section of the Topica, discuss fallacious arguments, that is, those which appear logical but of which the reasoning is invalid. The text is concerned with the tactics for the questioner and for the answerer and show how to detect weaknesses in the arguments of the other. These three works had a great influence on the study of logic in the Middle Ages and were particularly useful for the university practice of public disputations.

Sources used for this contribution:

Smith, Robin, "Aristotle’s Logic", The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Fall 2020 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.), forthcoming URL = <https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/fall2020/entries/aristotle-logic/>.

Rapp, Christof, "Aristotle's Rhetoric", The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Spring 2010 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.), URL = <https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/spr2010/entries/aristotle-rhetoric/>.

Contribution by Katia Riccardo.

Cite as, Katia Riccardo, “Text portaits”, The art of reasoning in medieval manuscripts (Dec 2020), https://art-of-reasoning.huygens.knaw.nl/text-portraits. ↑

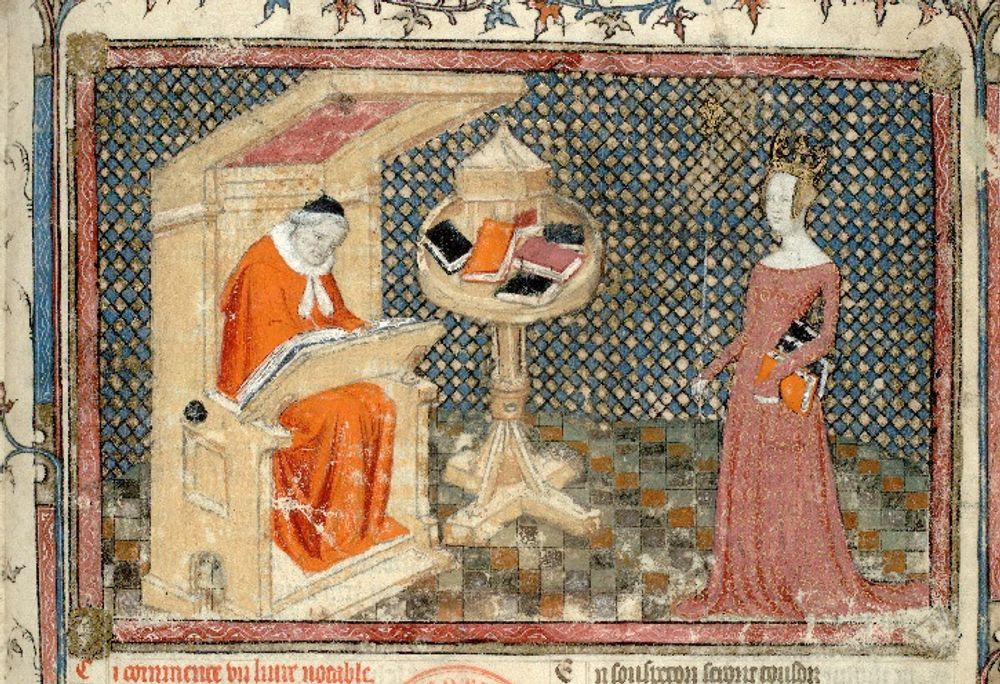

Boethius wrote his Consolation around the year 523. The book is a dialogue between Lady Philosophy and himself. Philosophy consoles Boethius in the hard times he has fallen on: accused of treason, he was incarcerated by the King of the Ostrogoths Theoderic the Great. In the book, Philosophy emphasizes the transient meaning of earthly fortune, such as fame and wealth, and argues for the superiority of things of the mind: happiness comes from within, from wisdom and understanding. The book engages with Christian themes such as free will and predestination, but approaches these from the perspective of natural philosophy and Greek classical philosophy alone. It is an example in how to apply ancient philosophical ideas to a discourse which is very Christian in nature. The book was very popular in the Western literary tradition. Many copies survive, together with translations, commentaries and adaptations.

http://initiale.irht.cnrs.fr/codex/7492/8196

Source used for this contribution:

Marenbon, John, "Anicius Manlius Severinus Boethius", The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Winter 2016 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.), URL = <https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/win2016/entries/boethius/>.

Contribution by Mariken Teeuwen.

Cite as, Mariken Teeuwen, “Text portaits”, The art of reasoning in medieval manuscripts (Dec 2020), https://art-of-reasoning.huygens.knaw.nl/text-portraits. ↑

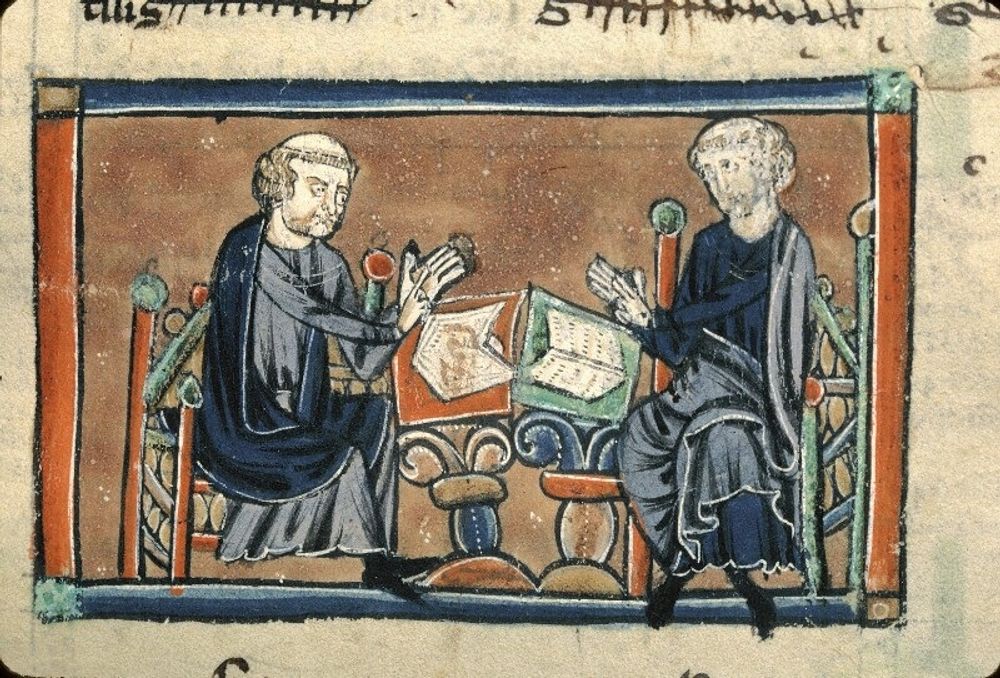

Boethius (ca 475/7 CE – 524/26 CE) was a Roman philosopher who had a thorough, Greek education. He spent most of his life pursuing the ambition to translate the Greek learning of his time into Latin. His translations and commentaries on logic were key for the transmission of Aristotelian logic to medieval logicians. The surviving works are: De divisione (“On division”), De syllogismo cathegorico (“On categorical syllogism”), Introductio ad syllogismos cathegoricos (“Introduction to categorical syllogisms”), De hypotheticis syllogismis (“On hypothetical syllogisms”), and De topicis differentiis (“On topical differences”). These texts offer a clear presentation of the Aristotelian doctrine in logic. They are thoroughly didactical in nature: they are student guide-books in how to master the art of reasoning.

http://initiale.irht.cnrs.fr/decor/34208

De divisione is a study about the various ways to divide things. There are two types of division: intrinsic (per se) and accidental (per accidens). Intrinsic division can be of a genus into its species, of a whole into parts, and of a word into its different meanings. For example, a substance can be divided into corporeal (e.g. body) and incorporeal (e.g. soul) substances, and corporeal substances can be divided into animate (e.g. horse) and inanimate (e.g. stone). Accidental division can be of a subject into accidents (e.g. of all men, some have brown eyes, some blue, some brown), of an accident into subjects (e.g. some things are found in the soul, some in bodies), and of an accident into accidents (e.g. of all animate things some are hard, some are soft).

De syllogismo cathegorico is a basic handbook for understanding syllogisms in two books. In the Introductio ad syllogismos cathegoricos the first book is discussed in more detail. The key words for understanding these works are propositions and syllogisms, which provided a methodology for constructing a logical argument. A proposition is a subject and predicate linked with a verb (e.g. all cats are animals); a syllogism is a type of argument consisting of two premises (propositions) which lead to a conclusion.

De hypotheticis syllogismis introduces the general theory of hypothetical syllogisms: those in which one or more premises are hypothetical sentences. While a categorical sentence makes a predication (e.g. Plato is a philosopher), a hypothetical sentence involves a condition (e.g. if it is day, it is light).

It is largely due to Boethius that in the Middle Ages the Topica of Aristotle and Cicero were revived. His tradition of topical argumentation was influential throughout the Middle Ages and into the early Renaissance. De topicis differentiis (“On topical differences”) is a treatise in four books on topical argumentation, which is an argumentation based on so-called topoi or loci. It is concerned with the discovery of arguments; the instrument for doing so is a topic, a place which the memoriser pictures in his mind and from which he recalls what he wants to remember. The memoriser familiarizes himself with, for instance, objects in a room, and fixes them in his memory in a certain order. He then divides his speech into parts and each object is associated with a part of the speech. The method can change depending on the use, for legal or political speeches or in dialectic for philosophical and theological inquiry.

Source used for this contribution:

Marenbon, John, "Anicius Manlius Severinus Boethius", The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Winter 2016 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.), URL = <https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/win2016/entries/boethius/>.

Contribution by Katia Riccardo.

Cite as, Katia Riccardo, “Text portaits”, The art of reasoning in medieval manuscripts (Dec 2020), https://art-of-reasoning.huygens.knaw.nl/text-portraits. ↑

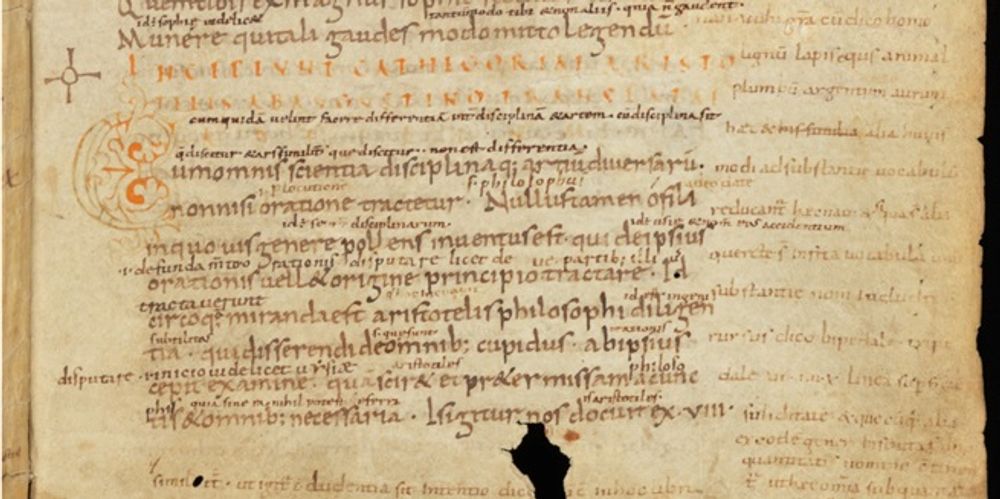

The Categoriae Decem (“Ten Categories”) is a late fourth-century Latin summary of Aristotle’s Categories. In the entire Middle Ages it was attributed to Augustine, which surely contributed greatly to its popularity and authority. Together with Boethius’ translation and commentary of the Categories, this Pseudo-Augustinian version became the main text used for dealing with the Aristotelian Categories since the sixth century.

https://www.e-codices.unifr.ch/en/list/one/csg/0274

The Categoriae Decem was indeed the principal source through which scholars gained their knowledge of the Categories. The text contains an introductory section which discusses the distinction between words, which signify, and things, which are signified. In the second section Aristotle’s classification of logical terms under ten categories is treated. Furthermore it treats the crucial definitions of ‘substance’ and ‘accident’: ‘substance’ is that which describes what something is (e.g. “Socrates is a man”) and ‘accidents’ are the properties of the substance which are not essential for its being (e.g. “Socrates is eating, Socrates walks through the streets”, etc.). These accidents are divided into ten categories. The text appeared as a summary of the Aristotelian work intermingled with commentary. It was this part of the text that mainly drew the attention of the early medieval scholars. When in the eleventh and twelfth centuries the interest in the more technical aspects of logic grew and new texts were found to satisfy that interest, the popularity of the Pseudo-Augustinian Categoriae Decem started to be eclipsed by Boethius’ version.

Source used for this contribution:

Studtmann, Paul, "Aristotle's Categories", The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Fall 2018 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.), URL = <https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/fall2018/entries/aristotle-categories/>.

Contribution by Katia Riccardo.

Cite as, Katia Riccardo, “Text portaits”, The art of reasoning in medieval manuscripts (Dec 2020), https://art-of-reasoning.huygens.knaw.nl/text-portraits. ↑

Marcus Tullius Cicero (106-43 BCE), Roman lawyer, orator, politician and philosopher, was one of the most influential figures in the Republican Roman politics. Almost immediately after his death, his extensive writings were canonised as classic models of rhetoric and philosophy. They were widely read and studied in the Middle Ages and beyond.

https://manuscripts.kb.nl/show/manuscript/66+B+13

Cicero wrote De Inventione (On invention), a work on rhetoric, when he was a young student. He completed two books, which deal with “invention”: the discovery of (seemingly) valid arguments. The goal was to write a complete treatise on rhetoric, where the sections of arrangement, expression or style, memory and delivery would have followed invention. If he ever indeed completed such a work, it did not survive to our time. The large number of manuscripts that survived of De inventione show that it was one of the most authoritative works for the western rhetorical tradition up to the Renaissance.

Similarly, the Topica, together with Boethius’ commentary, became a fundamental text for teaching rhetoric in schools and universities, and important for the development of scholasticism. The Topica, composed in 44 BCE, is an adaptation of the Topics of Aristotle, and illustrates how rhetorical invention should be conducted. The work was intended to be a textbook for practicing orators, such as lawyers and philosophers. Cicero’s aim was to articulate and simplify the contents of Aristotles’ Topics, whose technical language was difficult to grasp.

Contribution by Katia Riccardo.

Cite as, Katia Riccardo, “Text portaits”, The art of reasoning in medieval manuscripts (Dec 2020), https://art-of-reasoning.huygens.knaw.nl/text-portraits. ↑

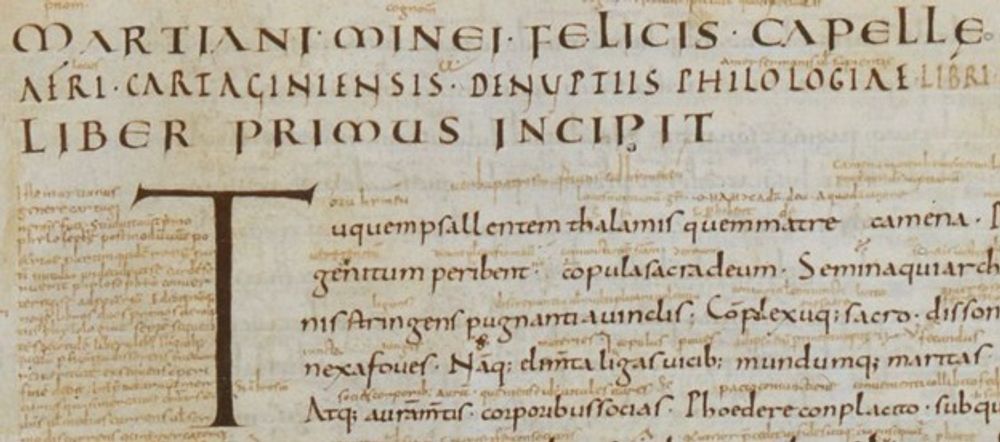

Martianus Capella is a fifth-century author from Carthago, North Africa, which was then a province of the Roman empire until the Vandals took over in 439 AD. Only one work of this author survived: De nuptiis Philologiae et Mercurii, “About the marriage of Philology and Mercury”. The work narrates the story of the god Mercury, who is looking for a suitable bride and finds her in the earthly lady Philology, a personification of all earthly knowledge and science. In this allegory, Mercury stands for heavenly knowledge, but also for the body of knowledge connected to language, or the trivium. Philology symbolically represents knowledge connected to number, or the quadrivium. Together, the couple personifies perfect knowledge. In the story, the couple receives an allegorically fitting gift from the gods to celebrate their marriage: seven ladies come to present their knowledge at the banquet. The ladies are personifications of the seven Liberal Arts, the arts of trivium and quadrivium. Grammar, Rhetoric and Dialectic are the three arts of language, Geometry, Arithmetic, Astronomy and Music are the four arts of number. For the medieval art of reasoning Martianus’ De nuptiis is crucial, because he is one of the most important sources for the establishment of the curriculum of the Seven Liberal Arts. Moreover, his treatment of the art of Dialectic provoked elaborate commentaries.

http://hdl.handle.net/1887.1/item:1618282

Source used for this contribution:

W.H. Stahl, R. Johnson, and E.L. Burge, Martianus Capella and the Seven Liberal Arts, Vol. 1: The Quadrivium of Martianus Capella: Latin Traditions in the Mathematical Sciences, 50 B.C.–A.D. 1250 (Records of Civilization: Sources and Studies, 84). New York: Columbia University Press, 1971.

Contribution by Mariken Teeuwen.

Cite as, Mariken Teeuwen, “Text portaits”, The art of reasoning in medieval manuscripts (Dec 2020), https://art-of-reasoning.huygens.knaw.nl/text-portraits. ↑

Together with Cicero’s De inventione and the Rhetorica ad Herennium there were a number of late Antique texts, composed by the so-called “minor Latin rhetoricians”. This body of texts constituted the school books for the study of rhetoric during the Middle Ages. They show the continuity of classical Greek and Roman rhetoric, how it flourished in the Later Roman Empire and became a core discipline taught in schools in the Middle Ages. These texts provided a synthesis and adaptation of the earlier sources, which were more elaborate and more complex to grasp, and thus met the practical concerns of medieval teaching. They all conformed to the rhetorical tradition of Cicero and Quintilian, but also showed Greek influence.

In the first century CE, Rutilius Lupus wrote the treatise De Figuris Sententiarum et Elocutionis. The text deals with the topic of elocution and figures of speech (anaphora, metaphor, oxymoron etc.). It consists of two books divided into 41 sections, each devoted to one of the figures, which are given a Latin spelling, a short definition, and an example, usually from a Greek orator.

https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b8478988x

Another treatise on figures of speech that adapted a Greek rhetorical work was written in the third century by Aquila Romanus (De Figuris Sententiarum et Elocutionis). Around a century later the rhetorician Julius Rufinianus added more figures (almost doubling their number). Two other short treatises written on the same subject, De Schematis Lexeos Liber and De Schematis Dianoeas.

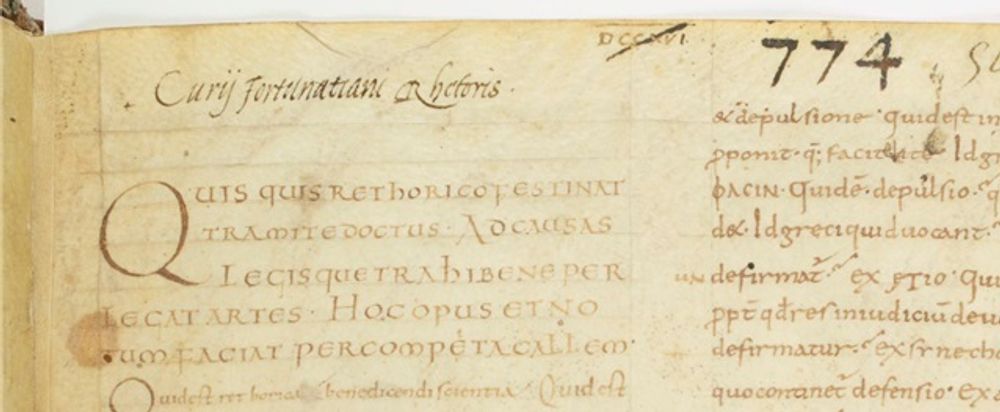

In the fourth century, Consultus Fortunatianus wrote his Ars rhetorica. It is a handbook in the form of questions and answers, meant for memorisation. For instance, the first question is “what is rhetoric?”, and the answer is: “The science of speaking well”. He discussed all five parts of rhetoric, but treated the part called “invention” in greater detail in the first two books. Other parts, such as arrangement, style, memory and delivery, were treated in the third book. Cicero’s orations are often cited as examples.

Marius Victorinus was a renowned fourth-century rhetorician and Neoplatonic philosopher active in Rome. He wrote a commentary on Cicero’s De inventione. The commentary incorporates many paraphrases in order to enable the students to understand the text better, and focuses on syllogism, the relation between rhetoric and logic and the terminology of De inventione.

Contribution by Katia Riccardo.

Cite as, Katia Riccardo, “Text portaits”, The art of reasoning in medieval manuscripts (Dec 2020), https://art-of-reasoning.huygens.knaw.nl/text-portraits. ↑

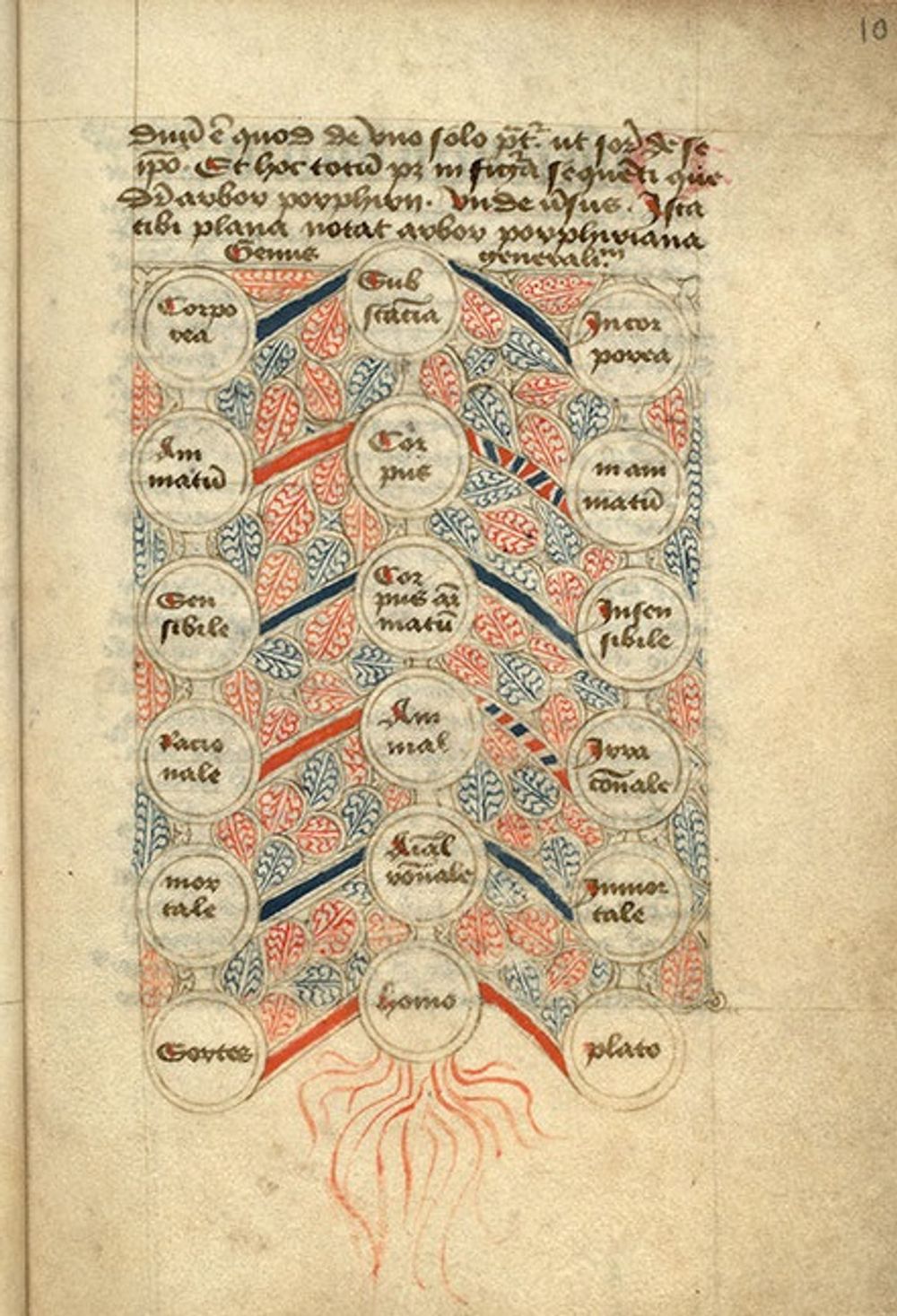

Porphyry was a philosopher from Tyre, Phoenicia (today Lebanon), active in the third century C.E. He wrote on all the relevant branches of knowledge of the time, including philosophy, religion, grammar, and natural science, but only a portion of his work survived. Porphyry was an important exponent of Neoplatonism, the dominant philosophical current of the period that reinterpreted the ideas of the ancient Greek philosopher Plato. In his philosophical writings Porphyry attempted to conciliate Aristotle’s logical works with Platonic doctrine. Porphyry is best known for the Isagoge, an introduction to Aristotle's logical works. It was translated into Latin by Boethius, and soon became an integral part of the Organon (“Instrument”; the set of logical works of Aristotle). It was one of the central texts for the study of logic in the medieval curriculum.

http://initiale.irht.cnrs.fr/decor/83261

The Isagoge is an elucidation of Aristotle’s doctrine on the five universals or predicables: genus, species, difference, property, and accident. Each of these explain what a substance consists of. Taking a typical medieval monk as an example (generally a European male human), genus is “animal”, species is “man”, difference is “rational”, property is “able to speak”, and accident is “white”. Most iconic in his work is a diagrammatic representation of the relationship between the predicables known as the Porphyrian tree. The Isagoge, in the Latin translation by Boethius, became deeply influential in the Latin West and one of the basic introductory texts for the study of philosophy for at least a thousand years.

Source used for this contribution:

Emilsson, Eyjólfur, "Porphyry", The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Winter 2019 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.), URL = <https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/win2019/entries/porphyry/>.

Contribution by Katia Riccardo.

Cite as, Katia Riccardo, “Text portaits”, The art of reasoning in medieval manuscripts (Dec 2020), https://art-of-reasoning.huygens.knaw.nl/text-portraits. ↑

The Latin text De Dialectica has been regarded as a work of Latin Church Father and Bishop of Hippo Augustine since at least the ninth century, but neither the manuscript tradition nor the tradition of the printed editions agree completely on this attribution. It is probably and adaptation of a Greek treatise that is now lost. It was Alcuin who attributed the text to Augustine. During the Carolingian time it was used as a textbook to teach dialectics. De Dialectica is a short scientific treatise on dialectic that remained unfinished. It serves as a brief account of the art of rhetoric in ten chapters. It gives a definition of dialectic as the science of “disputing well” (bene disputandi scientia) and it presents a discussion of a number of topics related to language. In particular, it is recognised that “we always dispute with words” (disputamus autem utique verbis). Words are then divided into two categories, simple words (simplicia) and combined words (coniuncta). Simple words are those which signify one thing, e.g. “homo ambulat” (“a man walks”). For combined words, the treatise gives the example “homo festinans in montem ambulat” (“a man walks in haste to a mountain”. Thus the statement is complicated in meaning by adding words to the simple structure of subject and verb. The text had a widespread circulation throughout the Middle Ages, both in monastic and cathedral schools and later in universities. It was an important text for the study of logic at the Faculty of Arts.

http://initiale.irht.cnrs.fr/decor/34302

Contribution by Katia Riccardo.

Cite as, Katia Riccardo, “Text portaits”, The art of reasoning in medieval manuscripts (Dec 2020), https://art-of-reasoning.huygens.knaw.nl/text-portraits. ↑

Rhetorica ad Herennium is a treatise about rhetoric addressed to Herennius. For a long time the work was attributed to Cicero. The reason for this attribution, which is now considered false, is that already in Late Antiquity the work was often copied together with Cicero’s rhetorical treatise De inventione. Due to its attribution to the famous ancient author, the treatise acquired a lasting name, fame and authority until well into the Renaissance. The two treatises were commonly used to teach rhetoric, the art of speaking well and effectively.

https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b10546175v

Rhetorica ad Herennium is composed in four books, that aim to prepare the speaker (orator) for speaking at the forum and especially the law courts. In medieval schools and universities it was re-purposed to teach how to argue in debates. The book has a famous description of a mnemonic technique: the memory can be trained by using visualizations of objects or events as points on an imagined journey along a route – the method of loci (places) or ‘memory palaces’. Because of its clarity and accessible style the Rhetorica ad Herennium became an essential textbook in the Middle Ages. The text was extensively translated into vernacular languages from the thirteenth century onward, and continued to be used as a standard school book on rhetoric during the Renaissance.

Contribution by Katia Riccardo.

Cite as, Katia Riccardo, “Text portaits”, The art of reasoning in medieval manuscripts (Dec 2020), https://art-of-reasoning.huygens.knaw.nl/text-portraits. ↑