Diagrams in the rhetorical tradition

Rhetoric and dialectic in schemes1

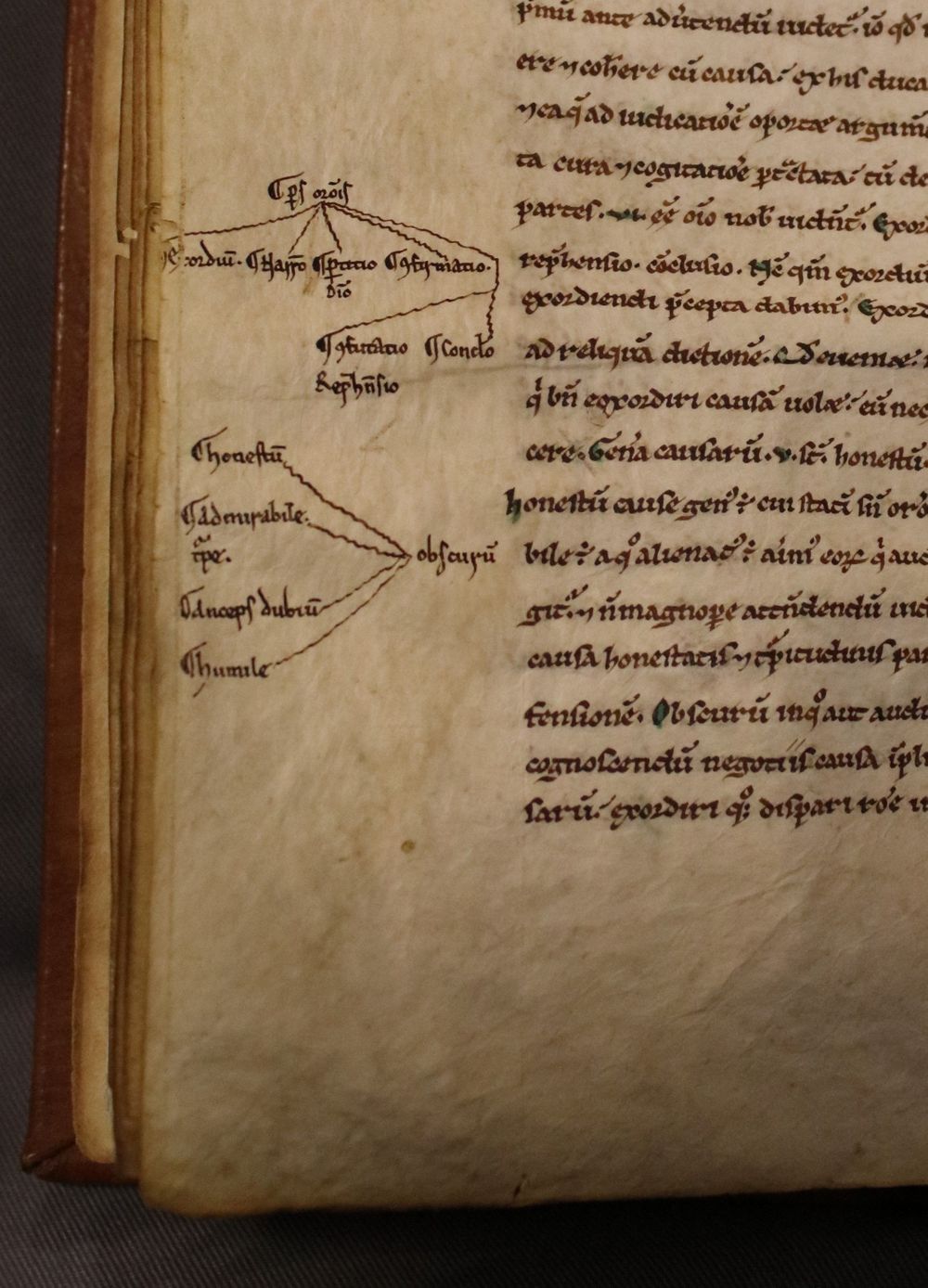

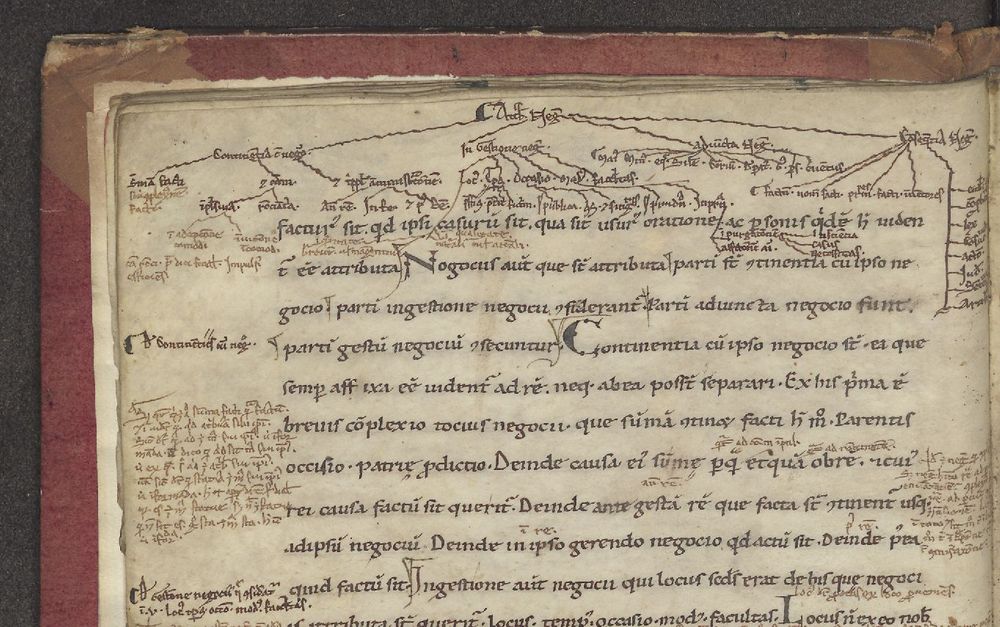

Diagrams were used to interpret, explain and summarise rhetorical and dialectical concepts for medieval readers. While they are often found, along with other (textual) annotations, in the margins of texts, we also find elaborated scheme series which offered a visualised overview of whole texts.

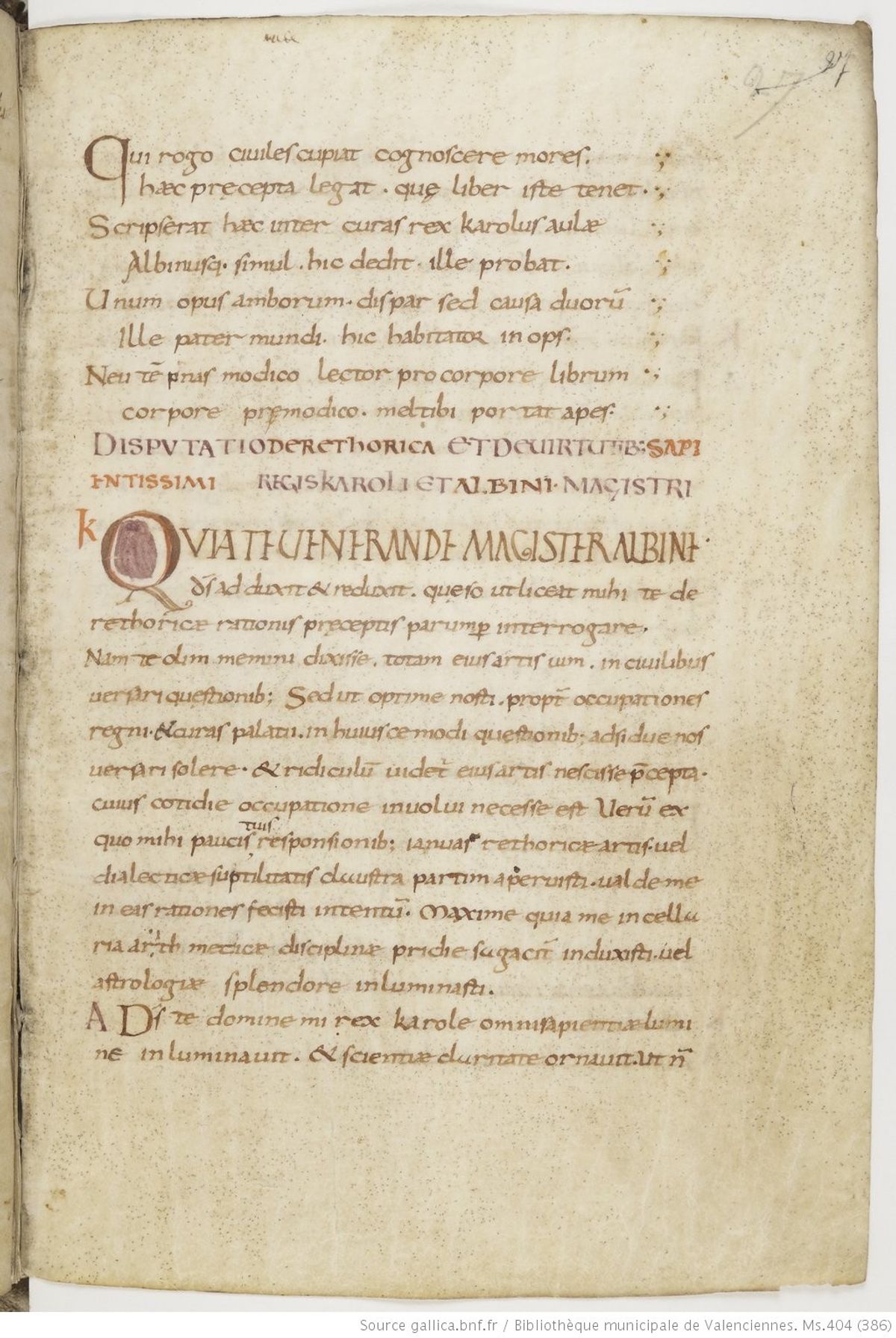

Alcuin (c. 735-804) was originally from York, but is famed for being an advisor to the emperor Charlemagne. In fact, one of his most renowned works, the Disputatio de rhetorica (written between 793-6), is composed in the form of a dialogue between him and Charlemagne, with Alcuin taking the role of master and Charlemagne that of the inquisitive student. The text opens with an epitaph praising the importance of rhetoric: “Whoever wishes to learn civil manners, let him read the precepts in this book”, establishing the Disputatio’s dual status as a rhetorical textbook and an advice book for an emperor.

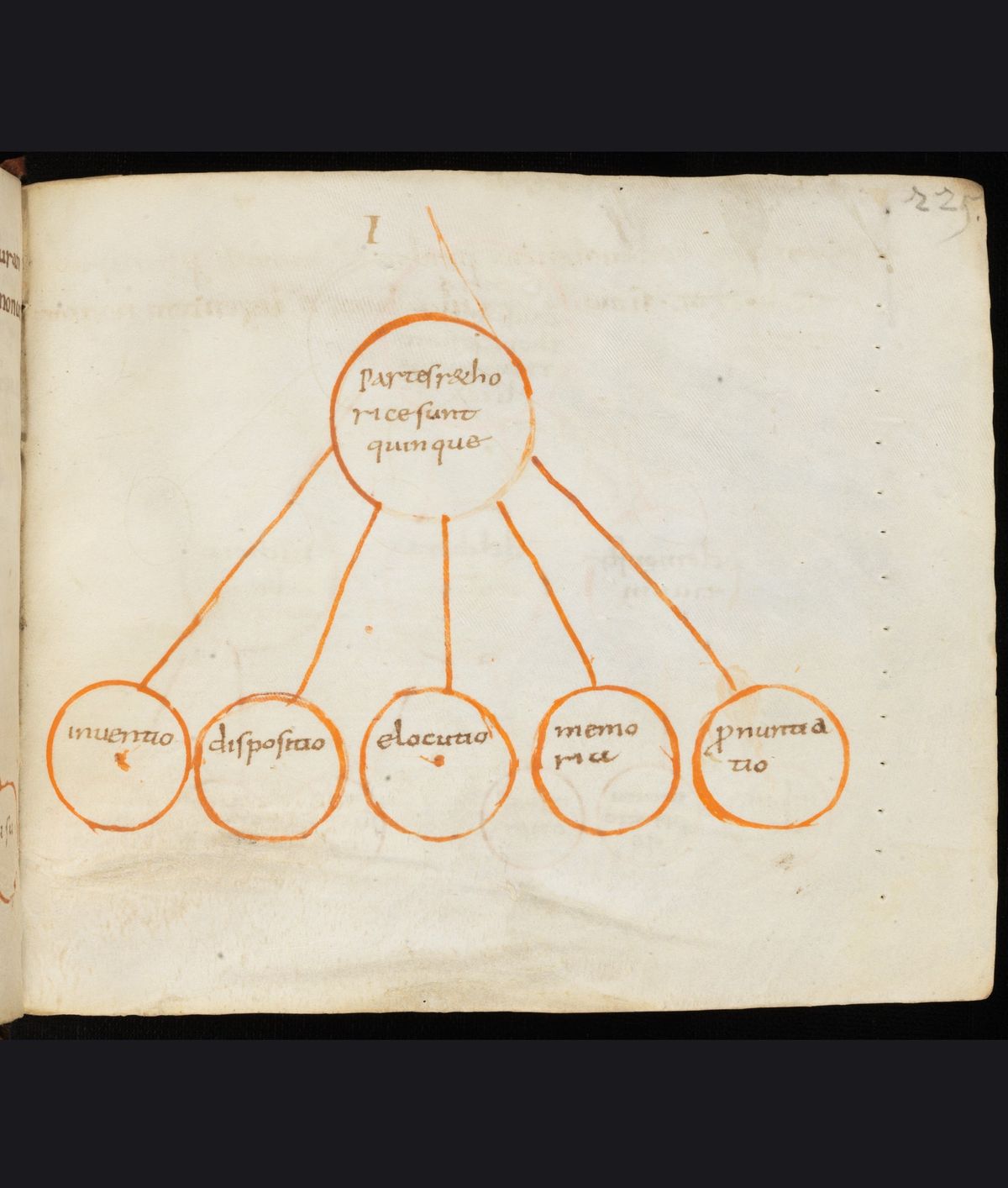

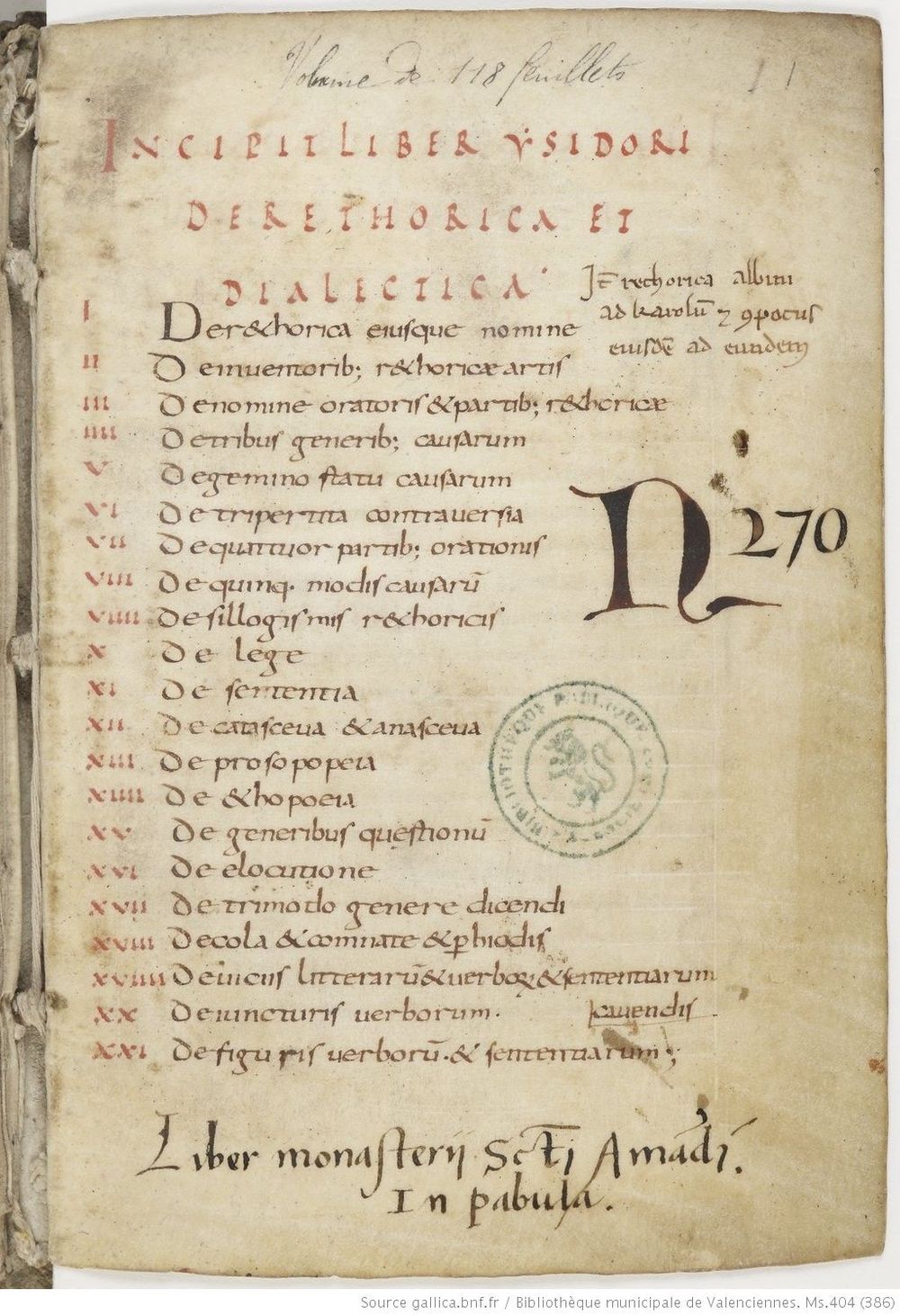

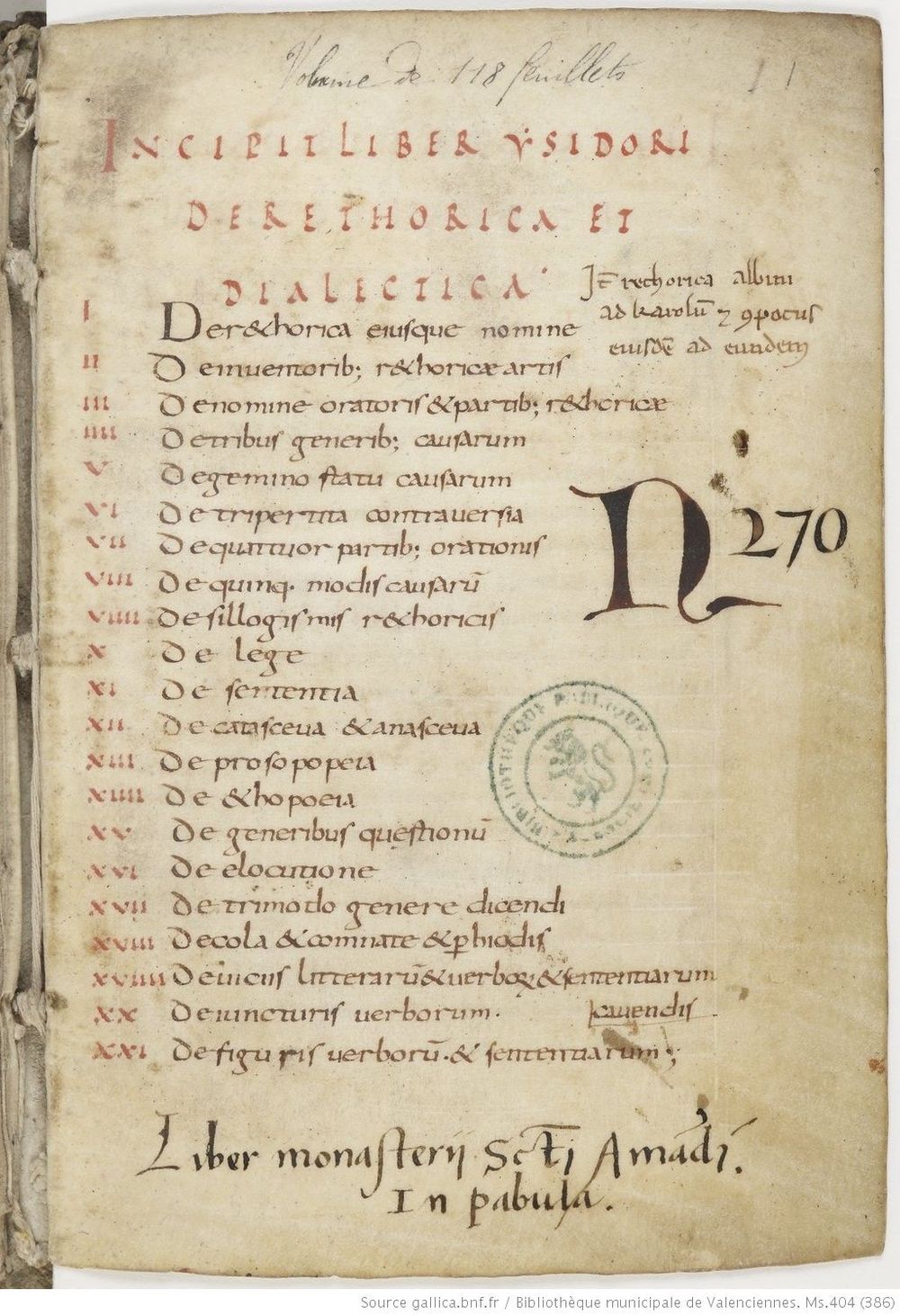

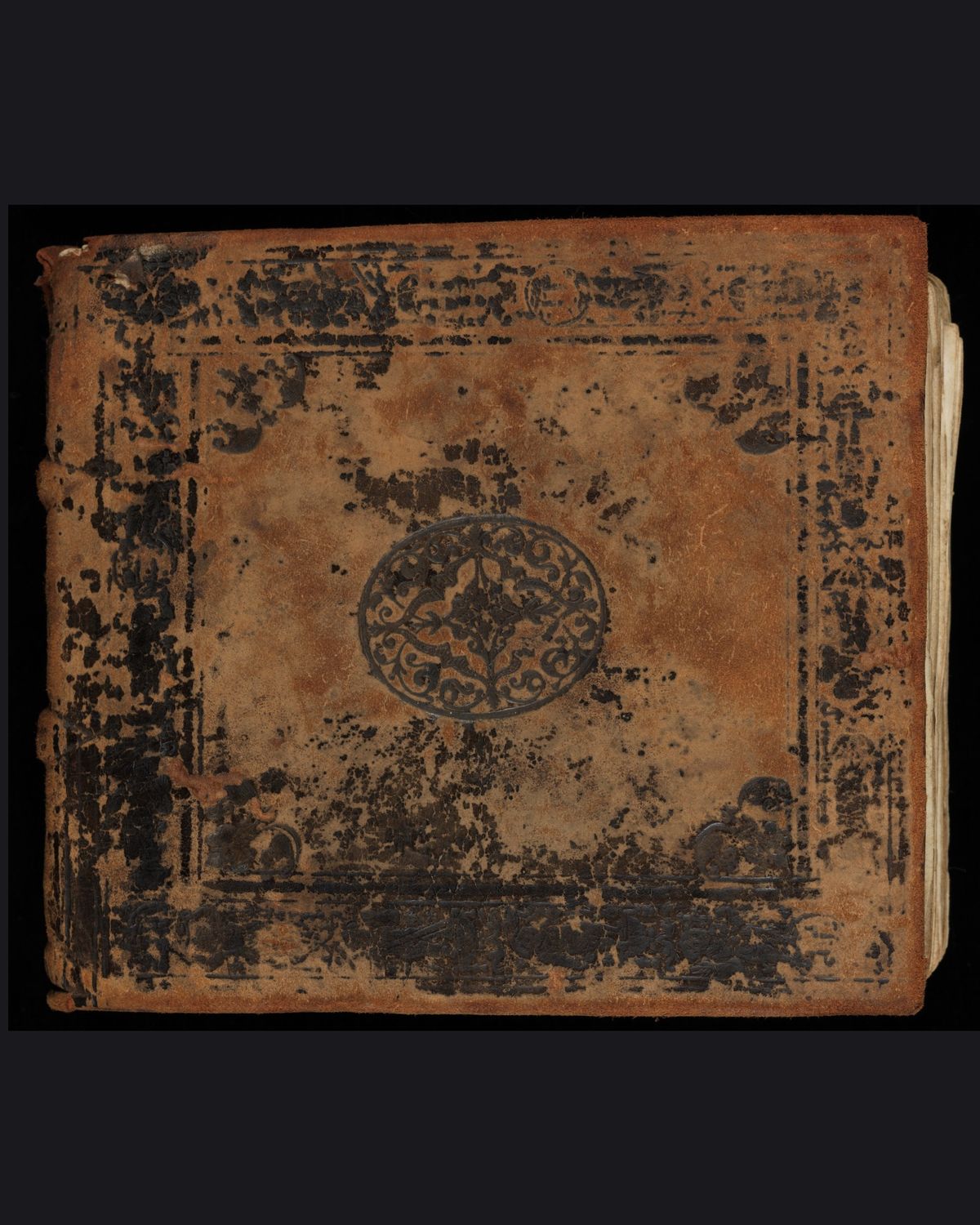

These two composite manuscripts (manuscripts containing multiple works) both date from the ninth century. Comparing their covers illustrates that they are completely different in terms of size and form, but both contain a copy of Alcuin’s Disputatio de rhetorica. In many copies of the text, including some of the earliest surviving exemplars, the Disputatio circulated along with a series of schemata. We don’t know whether Alcuin designed these schemata himself, or whether they were added by a contemporary reader to summarise his writings, but they were a popular addition to the text.

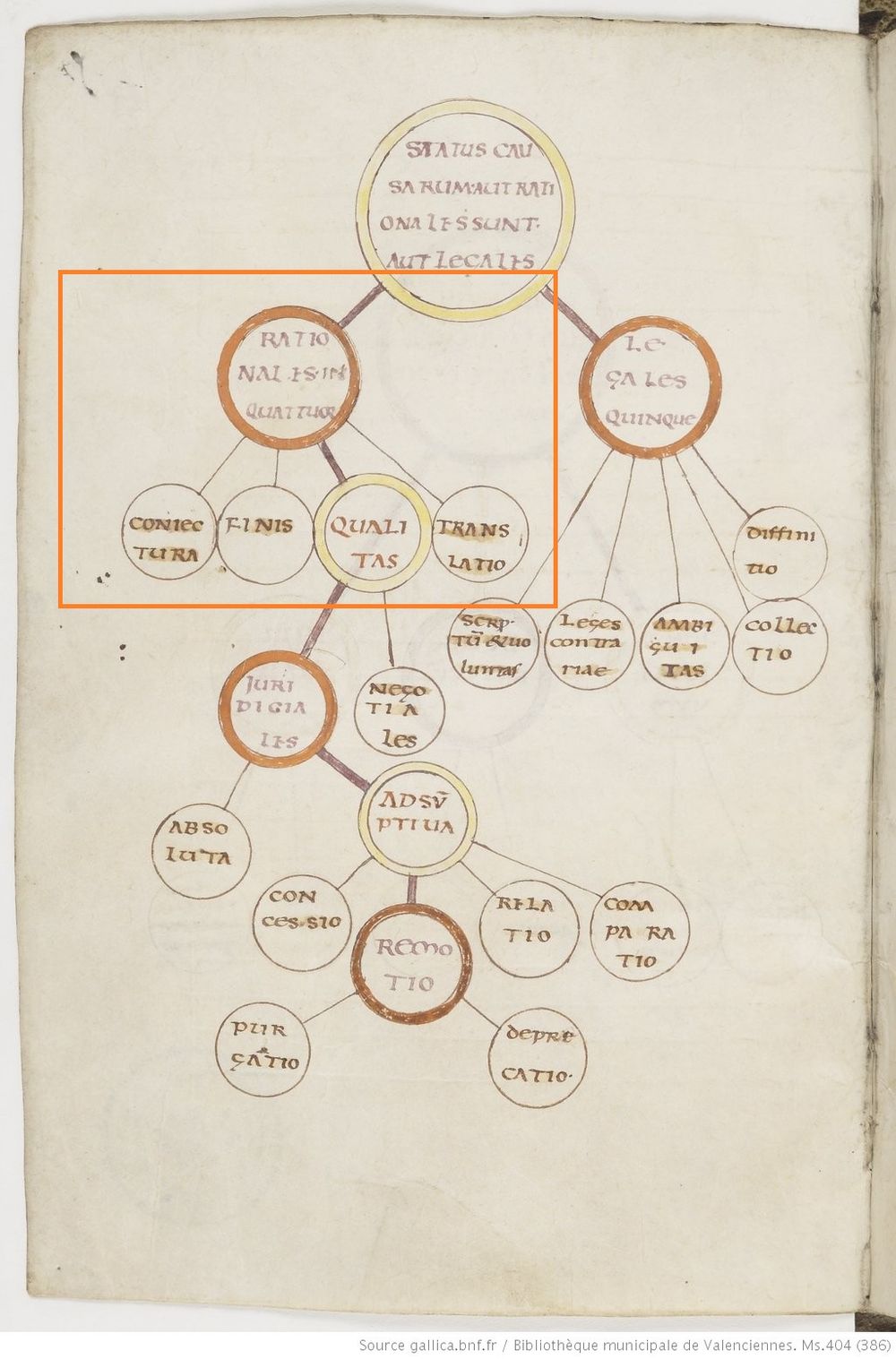

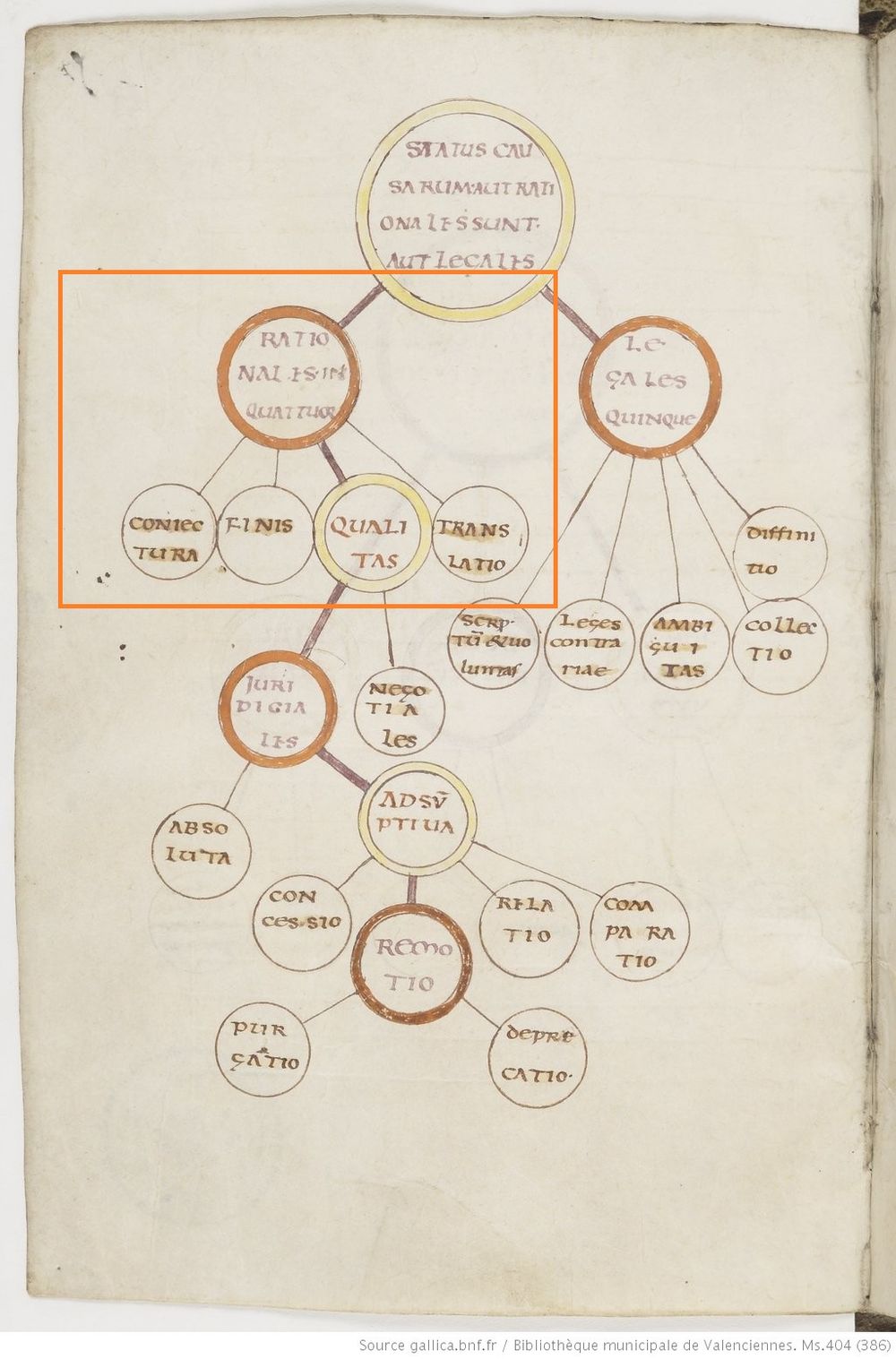

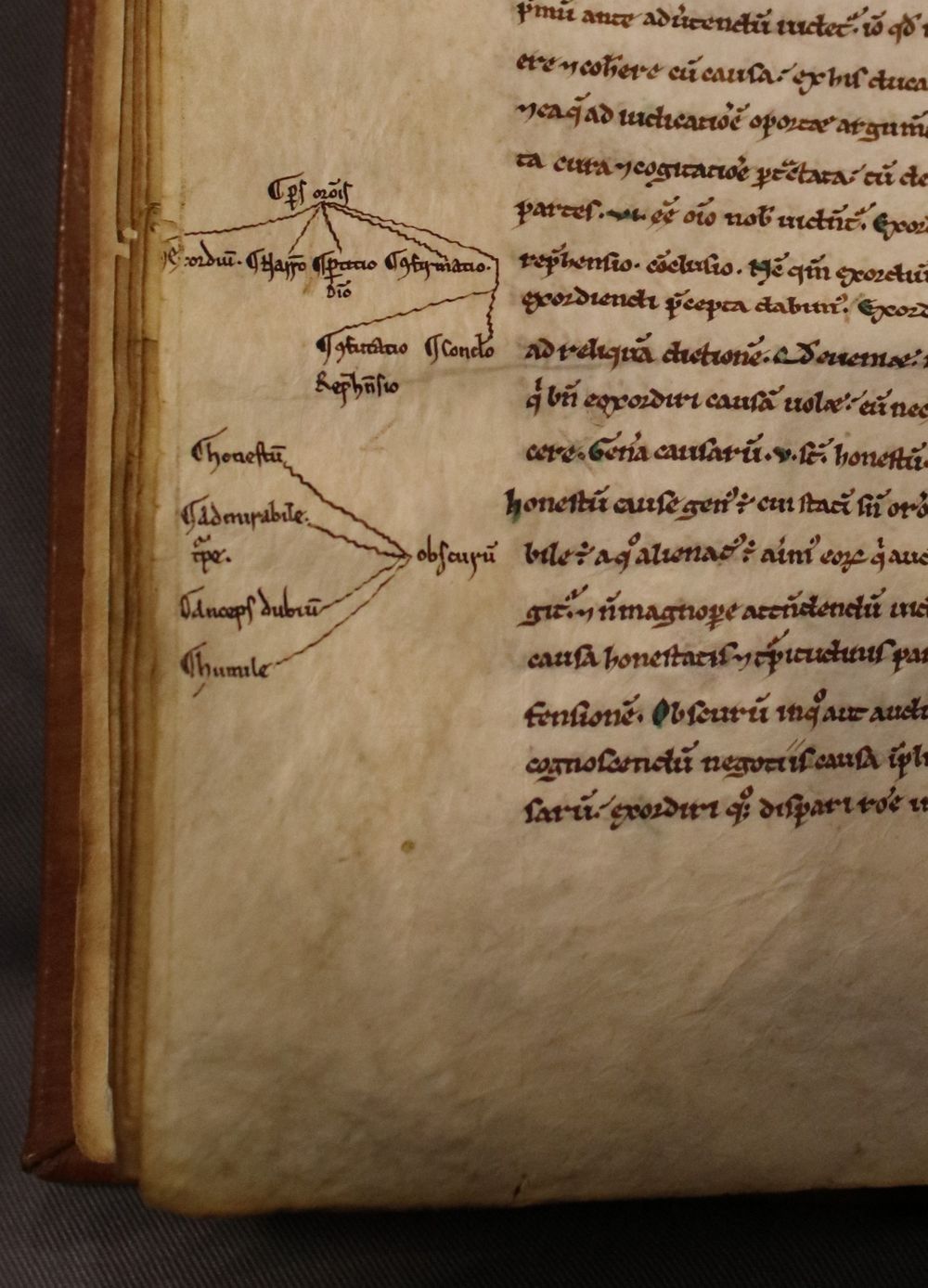

Some of the schemata are quite complex. In this scheme the subject is the use of the ‘status’ – the process of working out what the key issues of a dispute actually were. The highlighted branch concerns questions of ‘fact’. These can be: Conjectural – who did the act and when? (e.g. who is the murderer?) Definitional – how can we describe the act legally? (e.g. is it a murder or is it manslaughter?) Qualitative – in what context did the act take place, and does this affect our understanding of it? (e.g. was it a just killing?) Translative: Is the act being judged in the right court? (e.g. if it is a murder it should be judged at a higher court than a petty crime). Working step by step through these ‘issues’ helped the orator to structure a case effectively and establish an argument.

https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b8452582n

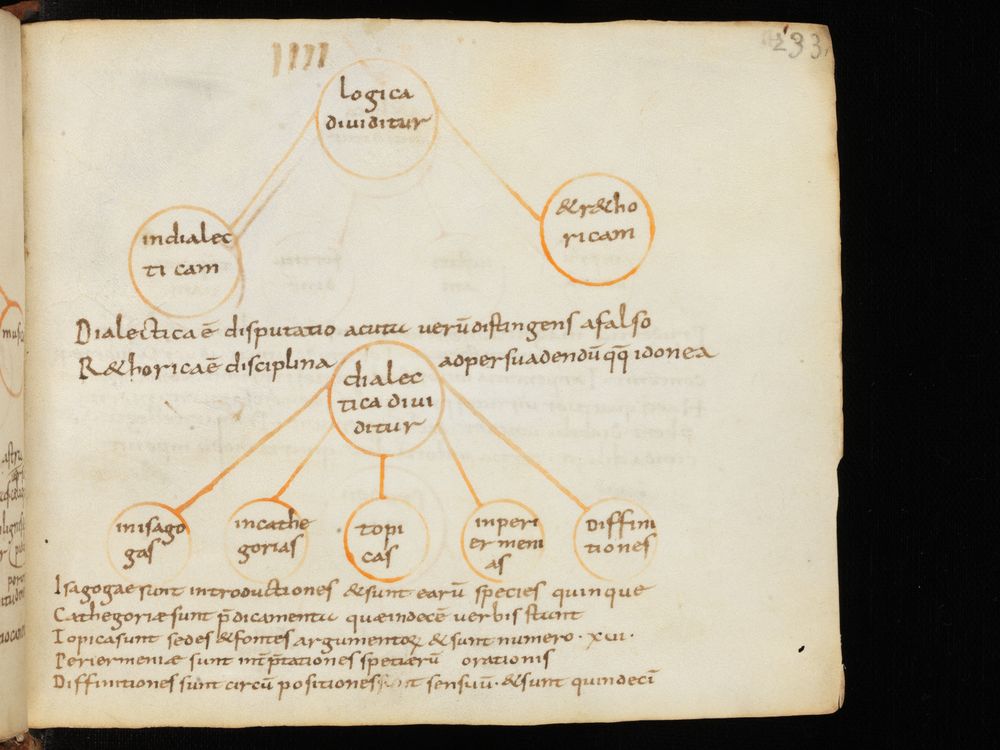

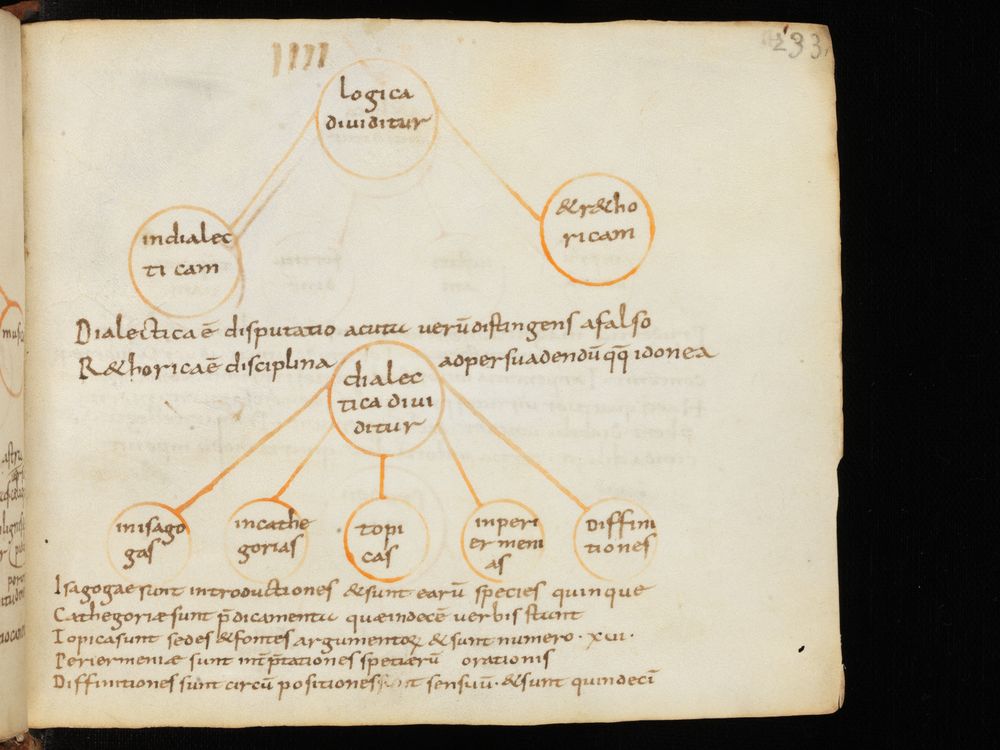

The schemata also helped the user to understand how rhetoric and dialectic related to each other. In the first scheme in St Gall, Stiftsbibliothek, Cod. Sang. 273, p. 233 both are described as parts of logic: “Dialectic is sharp disputation which distinguishes between truth and falsehood. Rhetoric is the discipline suitable for any kind of persuasion.”

https://www.e-codices.unifr.ch/en/list/one/csg/0273

The second scheme schematises the ’parts’ of dialectic, and is accompanied by a textual rubric:

”Isagogae are introductions and there are five species. Categories are predicaments of which there are ten terms. Topics are the seats and sources of arguments and number sixteen. Periermeniae are the interpretations of the species of speech. Definitions are the outlining of things which are perceived and are fifteen in number.”

https://www.e-codices.unifr.ch/en/list/one/csg/0273

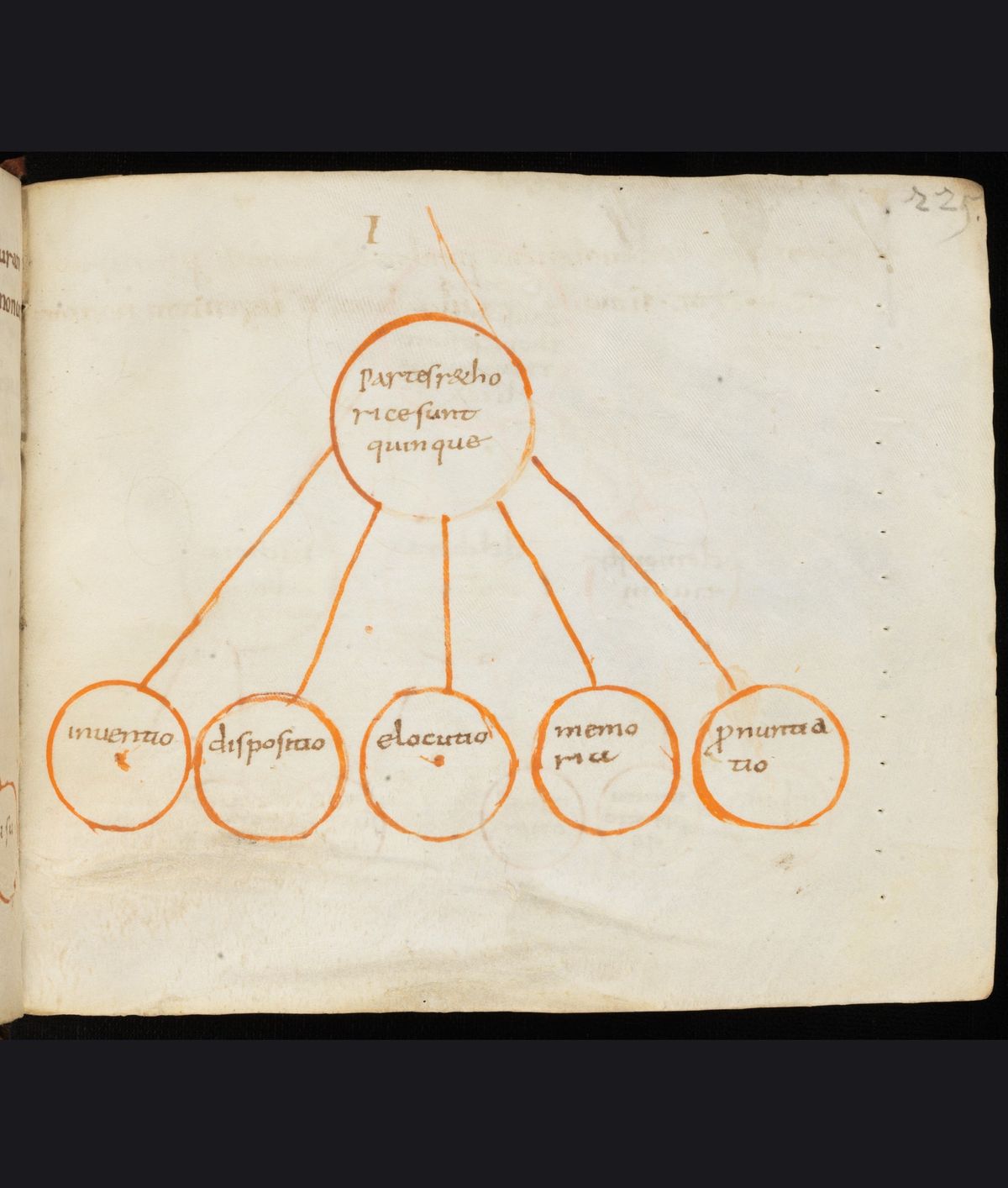

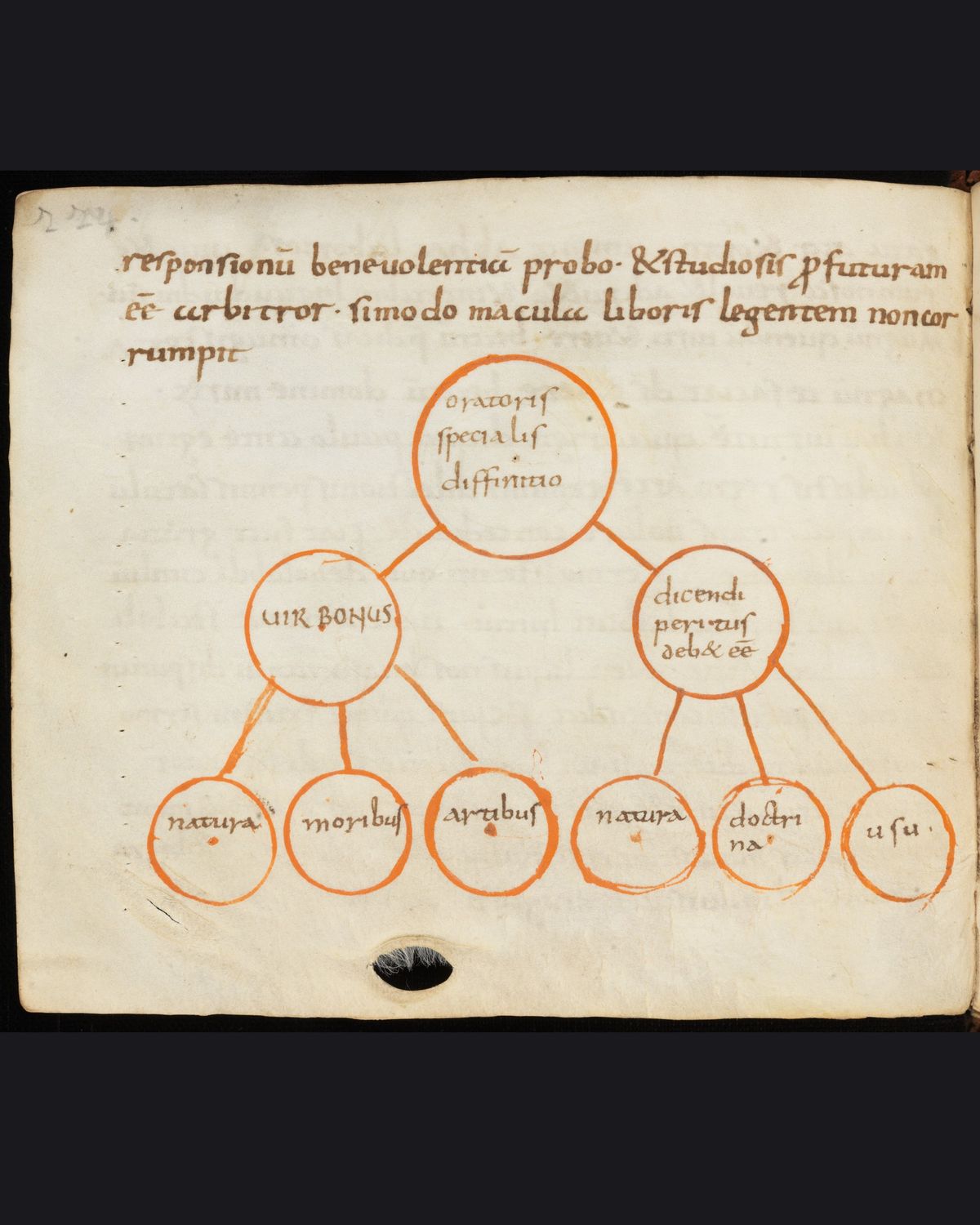

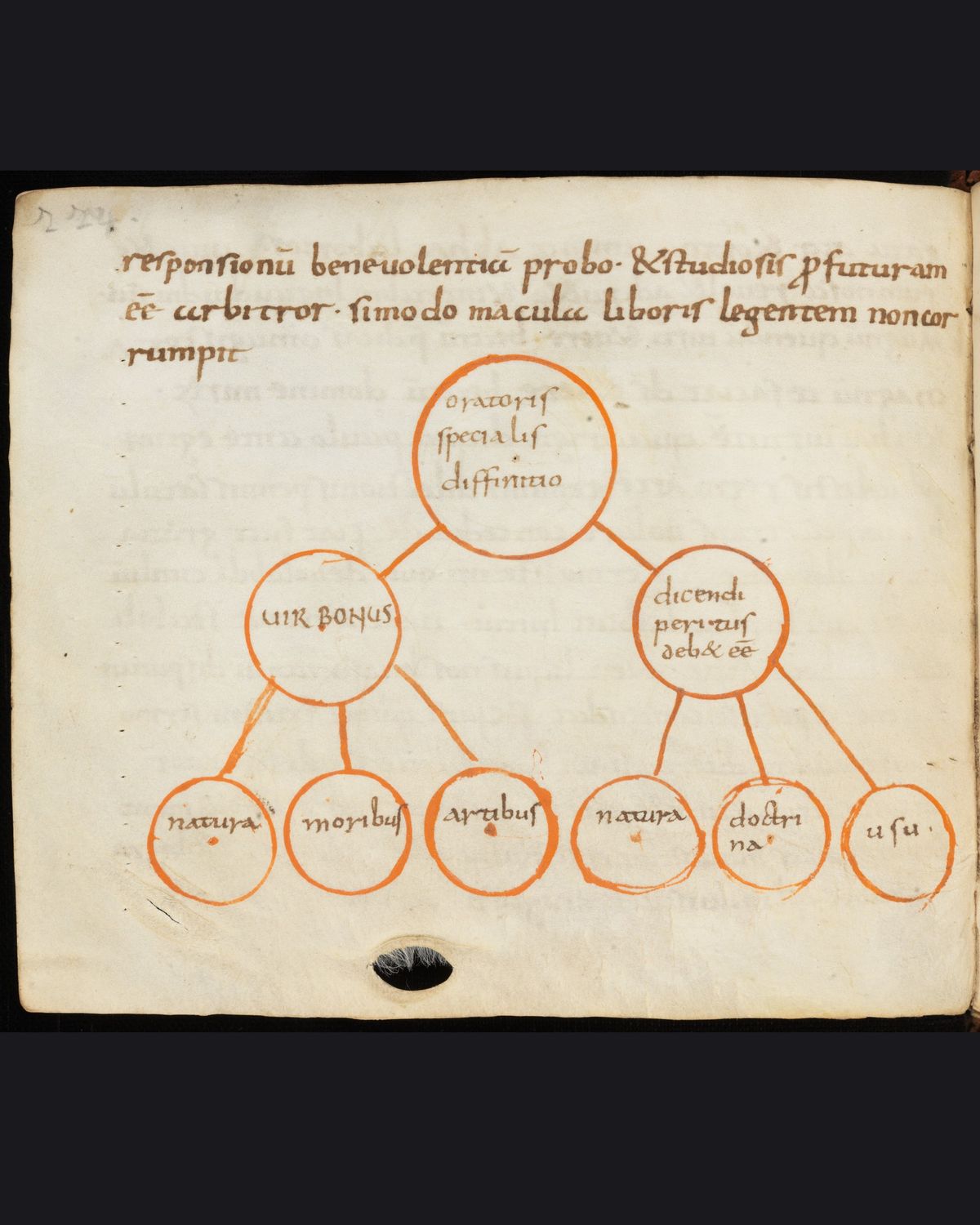

According to the classical tradition, acquiring rhetorical skill involved ethical training. In order to speak well you also had to be a good person. This scheme, the first in the series which circulated with the Disputatio, expresses this. Oratorical skill is acquired by nature, moral custom, art, instruction and use – you don’t just learn oratory from textbooks, but need moral guidance too. The scheme contains the words “Vir bonus dicendi peritus”, meaning “A good man is one who is skilled in speaking”.

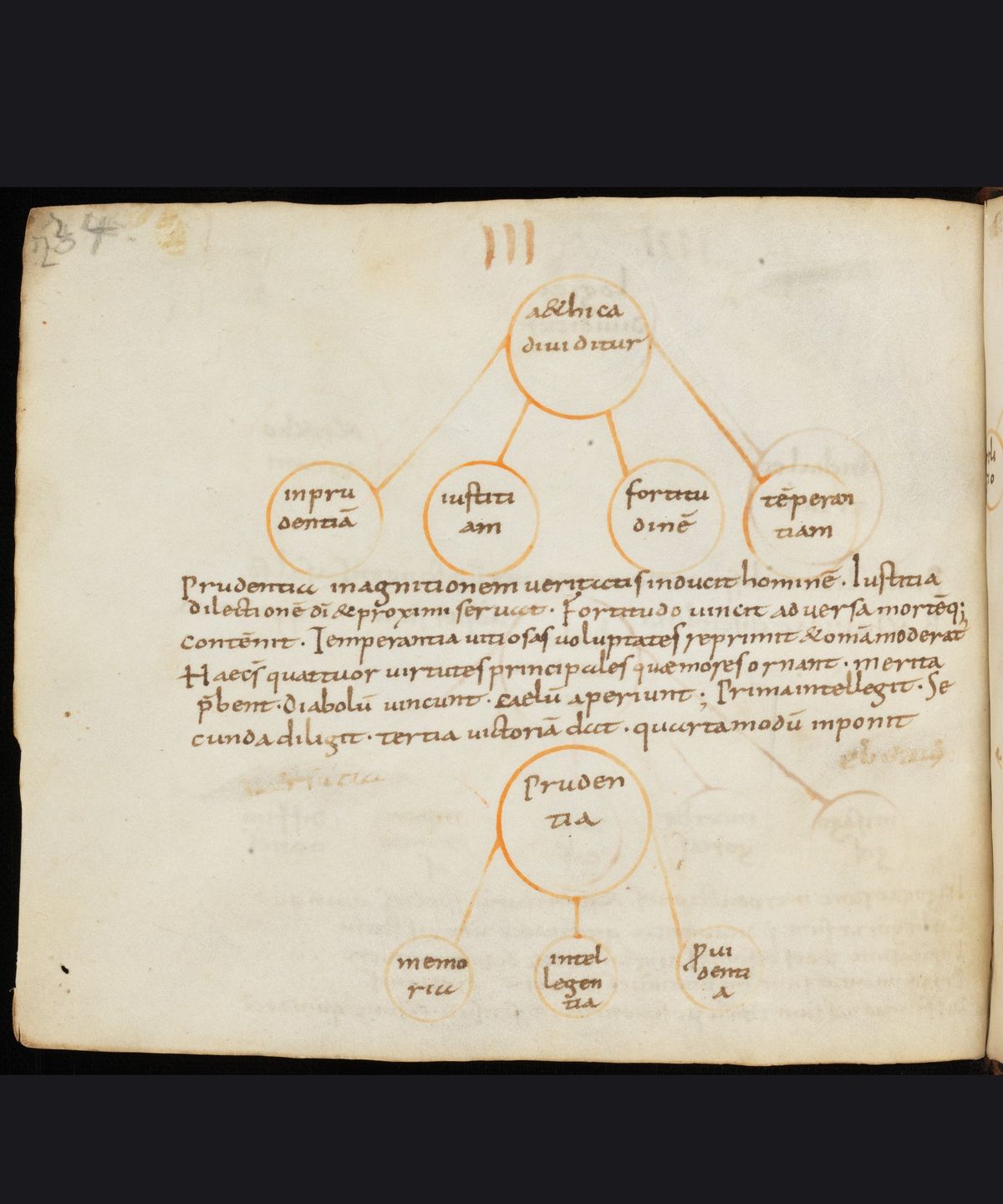

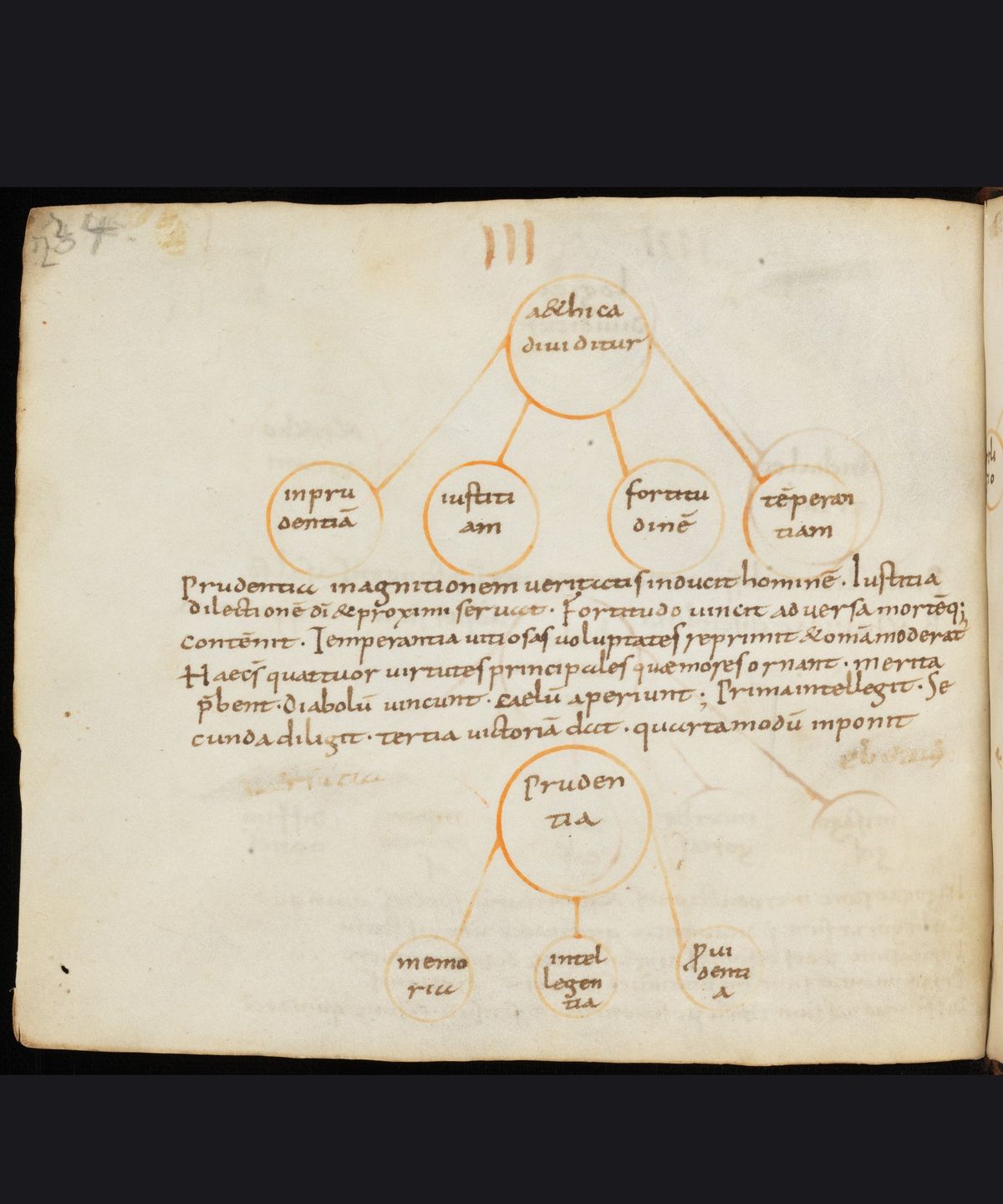

Thus, the orator had to learn how to become wise and virtuous. In these two schemes we find, first, the division of ethics into the four ‘cardinal’ virtues – prudence, justice, fortitude and temperance - then a smaller scheme giving the parts of prudence. This division of the virtues was popularised by Cicero (De inventione, Book II) and was sometimes combined by medieval writers with the ‘Christian’ virtues of faith, hope and charity. Here the caption adds a Christian spin. After defining the virtues, it adds ‘these are the four principal virtues which decorate morals, produce merit, defeat the devil and open heaven’.

The two examples of this schematic series discussed here come from Saint Gall and Saint Amand, important centres of learning in the Carolingian period. We can imagine that Alcuin’s works and their associated schemata were popularised not only because they were useful guides to the study of dialectic and rhetoric but also because of their association with Charlemagne. Schemata may have been useful to students in these Carolingian centres as summary devices or as an aid to help them remember material. In the case of complex examples, such as the scheme explaining status, a diagram could help guide a reader through difficult parts of a text.

https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b8452582n

Annotating with schemata

Schemata were also used to gloss rhetorical manuscripts. These complex sketches in the margins of texts helped the reader understand, and presumably memorise, concepts. Find out about two manuscripts where schemata were extensively used by annotators: Leiden UB, VLQ 103 and Leiden, UB, GRO 22.

http://hdl.handle.net/1887.1/item:1668135

Sources used for this contribution:

Bischoff, B., 'Eine verschollene Einteilung der Wissenschaften', Archives d’histoire doctrinale et littéraire du moyen âge 25 (1958), 5-20

Evans, M., ‘The Ysagoge in Theologiam and the commentaries attributed to Bernard Silvestris’, Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes, 54 (1991), pp. 1-42

Howell, W. S., The Rhetoric of Alcuin and Charlemagne (Princeton, 1941)

Jullien, M. - H., Perelman, F. (eds), Clavis scriptorum Latinorum medii aevi [CSLMA], II: Alcuin (Turnhout, 1999)

Knappe, G., ‘Classical Rhetoric in Anglo-Saxon England’, Anglo Saxon England 27 (1998), 5-39 (pp. 13-15).

Migne, J.-P. (ed.), Patrologia Latina, vol. 101

O’Daly, I., 'Diagrams of Knowledge and Rhetoric in Manuscripts of Cicero’s De inventione', in E. Kwakkel (ed.), Manuscripts of the Latin Classics 800-1200 (Studies in Medieval and Renaissance Book Culture, Leiden University Press. 2015. 77-105)

Wallach, L., Alcuin and Charlemagne: Studies in Carolingian History and Literature (Ithaca, 1959)

Contribution by Irene O’Daly.

Cite as, Irene O’Daly, “Diagrams in the rhetorical tradition”, The art of reasoning in medieval manuscripts (Dec 2020), https://art-of-reasoning.huygens.knaw.nl/schemes. ↑

Next Read:

Next Read: