Rhetoric and dialectic

The skills of speaking and arguing1

After a pupil had learnt how to read and write in Latin (grammatica), it was time for a next level of knowledge of the language: learning how to speak well and effectively (rhetorica) and how to build arguments and reason well (dialectica). These skills were needed for many purposes: to speak well is an art needed to get your message across and to convince people, to be able to argue is important for a proper understanding of texts, for using them in debates and for deciding in cases of disagreement. Dialectica became a crucial element in theological debate. It also became a key element of the university curriculum: every student was thoroughly trained in the skill of dialectical reasoning with the disputatio, a formal game of two opponents reasoning against each other. In this image from the fourteenth-century manuscript Karlruhe, Badische Landesbibliothek, St.Peter perg. 92, Ramon Llull is portrayed as he is engaged in a dialogue with Thomas Le Myésier. On the left one can follow the structure of the debate, laid out in a diagrammatic form. The two discussants are pointing at the sources for their arguments: a stack of books.

https://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:bsz:31-8765

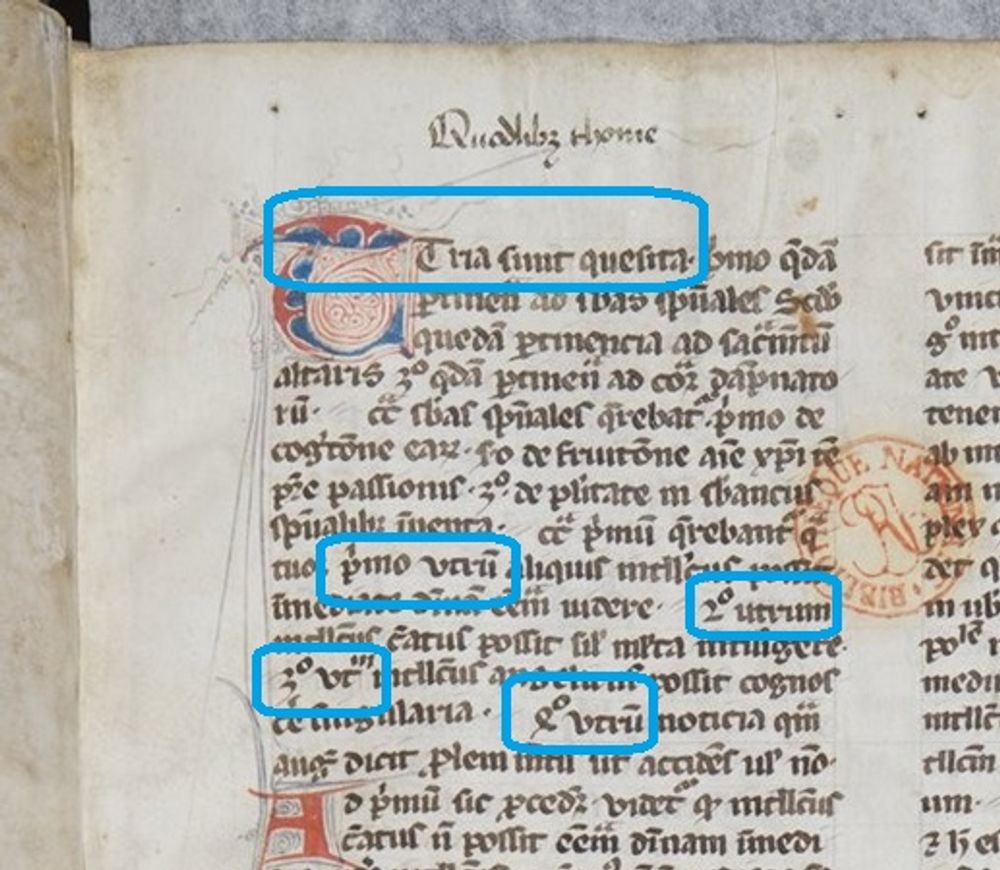

The art of arguing: dialectical disputation

The disputatio was an important instrument at the medieval university, as a teaching exercise but also as the most important exam: a formal public disputation was the final step to become a magister at the university. Today we still have a remnant of the medieval practice in many universities all over the world: a public defence of one’s thesis. The oral events were at times recorded in writing. The disputatio also became a literary genre, not necessarily preceded by an actual oral dispute.

The structure of a disputation

Step 1: A magister at the university decided on a question and allocated the roles of respondens (respondent) and opponens (opponent, or, generally, opponents). In an initial session the magister introduced the question as a dialectical question to be answered by yes or no.

Step 2: The respondens chose one of these answers, and gave arguments for his position. The opponens (or opponentes) attacked his arguments and his position with counter-arguments.

Step 3: The respondens was given the space to respond to the counter-arguments, and give new arguments against the counter-arguments and for his initial position.

Step 4: The magister decided who had won the debate, and gave his final solution (solutio) to the question.

https://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:bsz:31-8765

The game of arguing

To train the skill of disputing, several exercises were incorporated in the university curriculum. Obligationes (from the term obligatio, obligation or liability) were debates in which one committed oneself to uphold or deny a certain initial statement, after which one was then compelled to also uphold or deny everything that logically followed from that initial statement. It was a game of logical trickery, each party trying to lure the other in admitting to something impossible. Another exercise was the quodlibet, a special kind of disputation about a question on any topic and raised by anyone. The challenge was to be quick on one’s intellectual feet and show the ability to respond to questions of every nature and about any subject.

https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b525048552

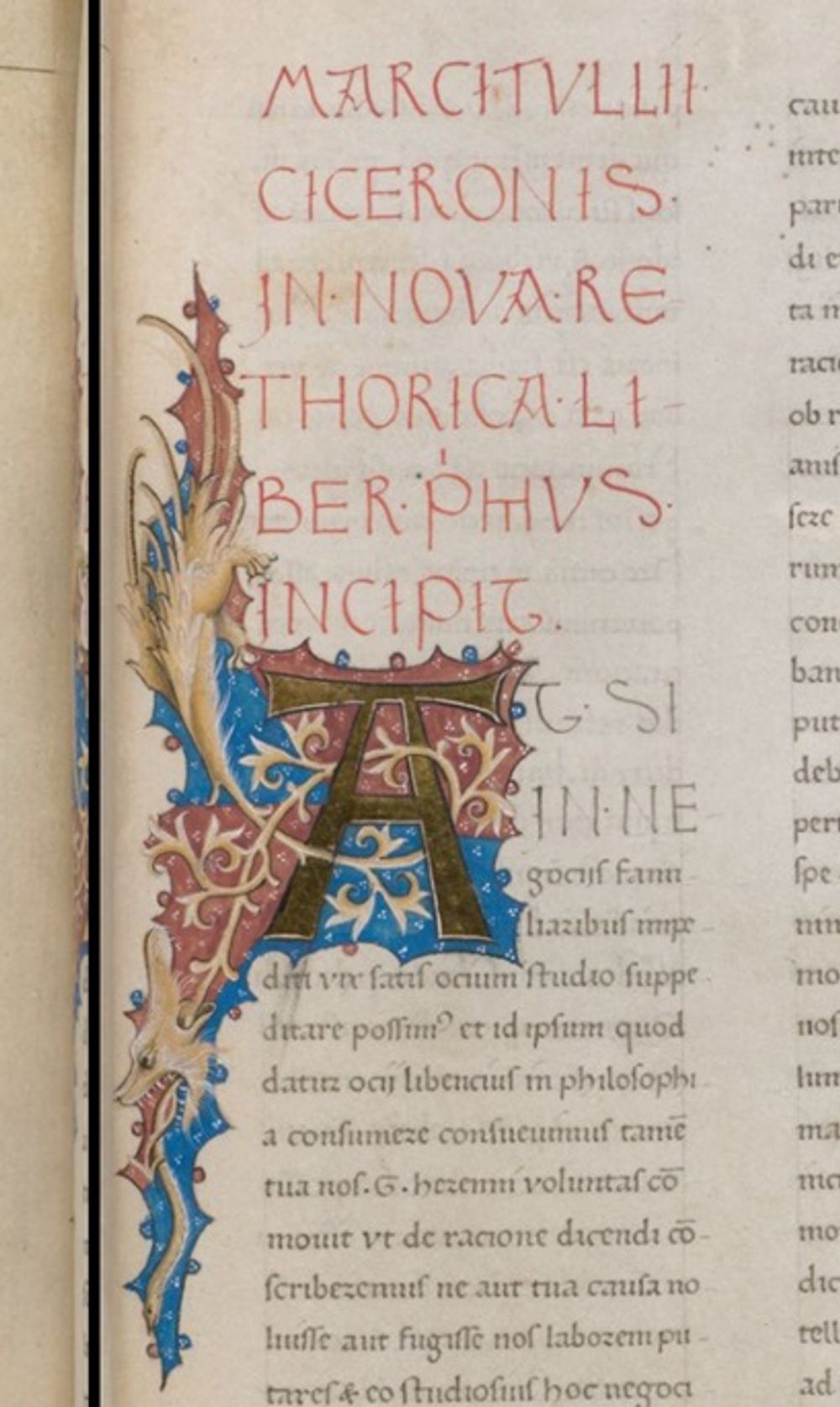

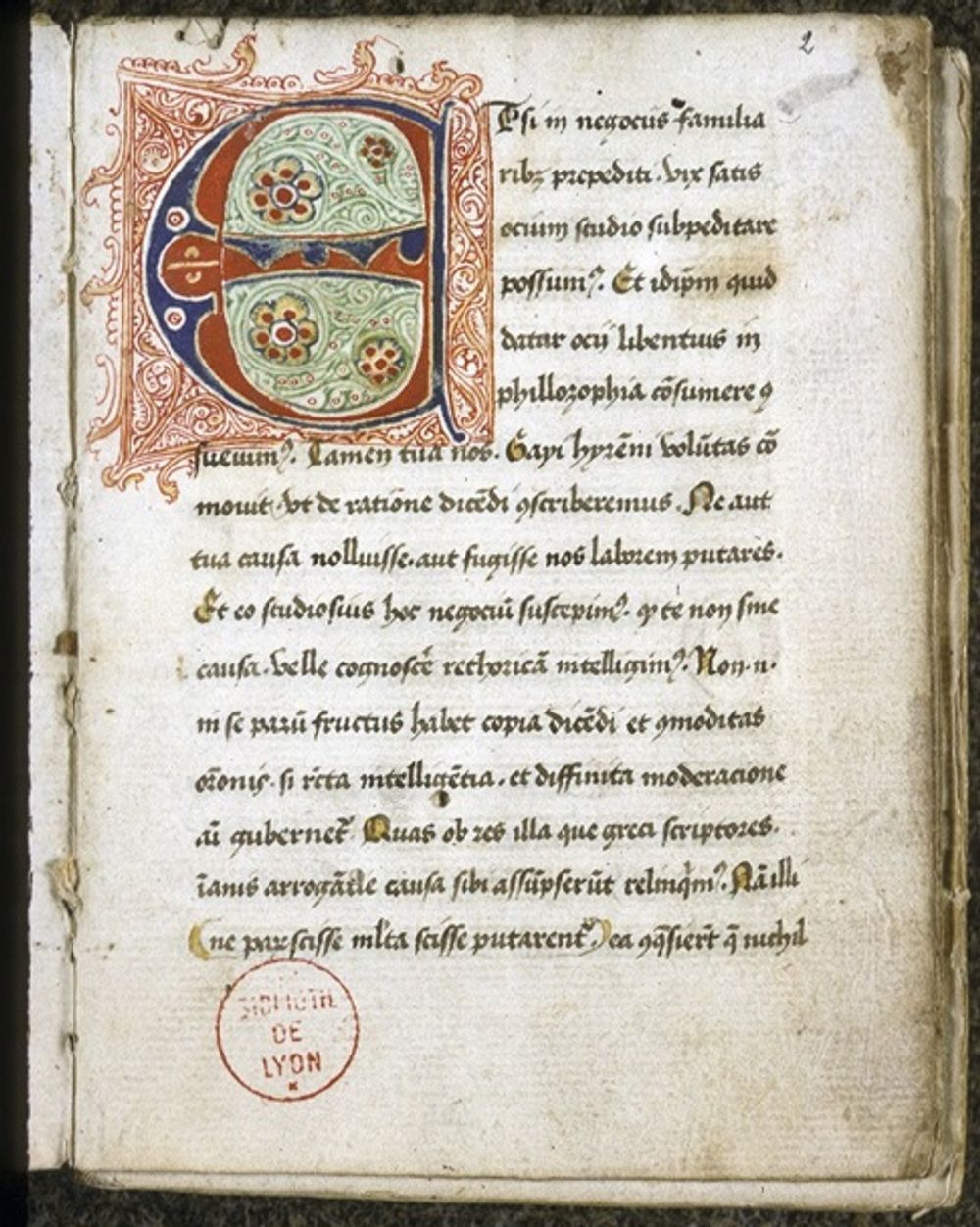

Rhetoric

Cicero’s De Inventione and the Rhetorica ad Herennium (unknown author but generally attributed to Cicero) were key texts for the study of rhetoric during the entire Middle Ages. Other late-antique texts that were used in the medieval study of rhetoric were the so-called ‘minor Latin rhetoricians’ such as Rutilius Lupus, Iulius Rufinianus, Fortunatianus and Marius Victorinus. Quintilian’s major rhetorical handbook, The Institutes of Oratory, circulated only in incomplete manuscripts. References to it from before the eleventh century are rare. In encyclopaedias, such as Isidore of Seville’s Etymologies, the fundamentals and terminology of rhetoric were discussed. Figures of speech, which one would perhaps expect to be treated here, were generally treated within the discipline of grammar.

https://parker.stanford.edu/parker/catalog/sp902vq7011

In the ninth century a new work entered the rhetorical curriculum: Alcuin’s Disputatio de rhetorica. In the eleventh and twelfth century a range of new rhetorical commentaries and treatises on the ars dictaminis (the art of composing letters) became a firm part of rhetoric. In rhetorical manuals the discipline was further divided up into specific, practical branches: the ars poetica, ars praedicandi, ars notariae, etcetera.

In the thirteenth century, together with the influx of Aristotelian logical texts, Aristotle’s Rhetoric was reintroduced in the Latin West, in a Latin translation of Herman the German (Hermannus Allemannus). This had an enormous influence on the development of the art of rhetoric: in constructing a general theory of persuasion, Aristotle firmly connected rhetoric to the arts of dialectic and logic. His philosophical approach was avidly picked up in the later Middle Ages.

http://initiale.irht.cnrs.fr/codex/2263/6742

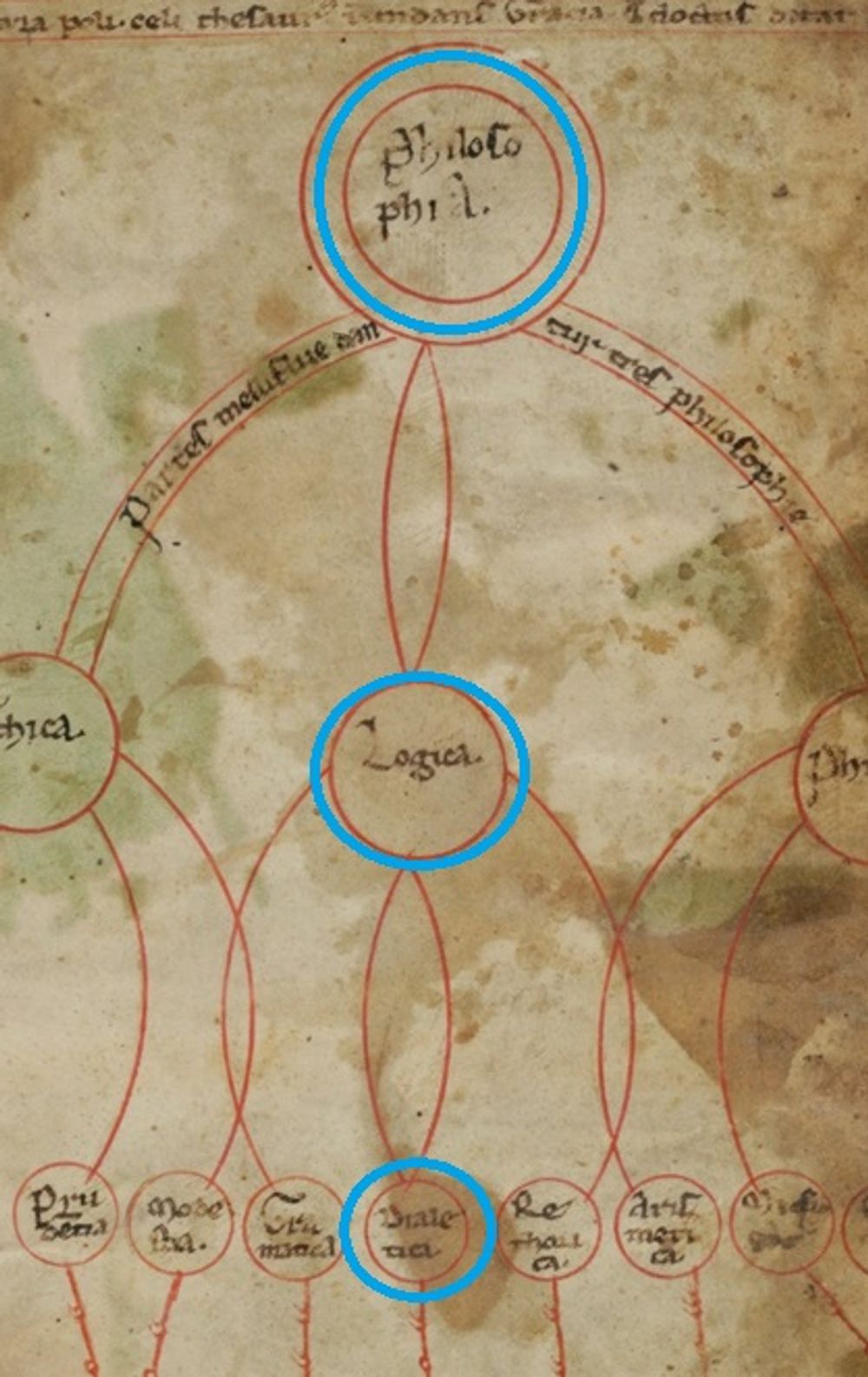

Dialectica and Logica

In some definitions, the art of dialectic and the art of logic were presented as separate, in some they were synonymous. One could make the distinction that Dialectic is the art of making a good argument, Logic of adhering to the rules of sound reasoning. The two were always closely linked to each other: in order to make a convincing argument, it had to make sense. For this reason these two arts were often treated in the same volume or text, or even as one and the same art. Logic, however, had its own set of curricular texts. The body of logical texts known and studied in the earlier Middle Ages is known as the Logica Vetus. In the twelfth and thirteenth centuries new texts were added, known as the Logica Nova.

https://www.e-codices.unifr.ch/en/list/one/fmb/cb-0188

Logica Vetus

Logica Vetus (Old Logic) is the set of logical works that were in available in the libraries and book collections of medieval Europe from the start. Several works of Aristotle are at the heart of this set, but some of his works came to the Latin West at a later point in time. These are not a part of Logica Vetus, but of Logica Nova, the new translations of Aristotle’s remaining logical treatises that came to the Latin West in the twelfth century. Many of the treatises of the Logica Vetus were made available by Boethius, who, in the late fifth/early sixth century made it his project to translate from Greek to Latin all the works of Plato and Aristotle and to provide commentaries on them. We have his translation of Aristotle's Categories and On Interpretation, and Porphyry’s Isagoge. He also composed supplementary works, such as the Book of Six Principles and works about syllogisms, a crucial tool for logical reasoning. The texts of Logica Vetus played a major role in the formation of the discipline of dialectic and logic. They were studied from the early Middle Ages on, and remained in use in the times of the medieval universities.

http://tudigit.ulb.tu-darmstadt.de/show/Hs-2282

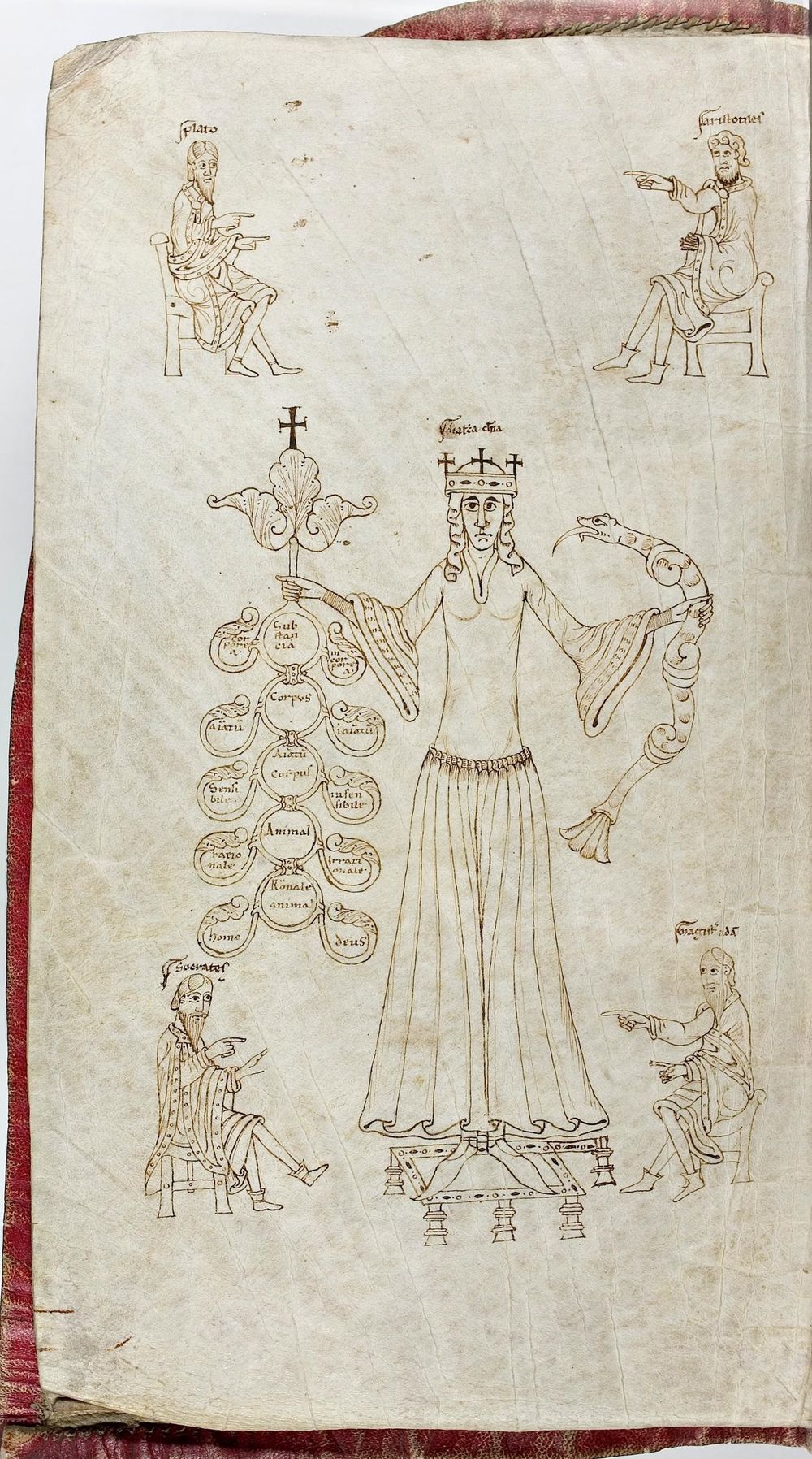

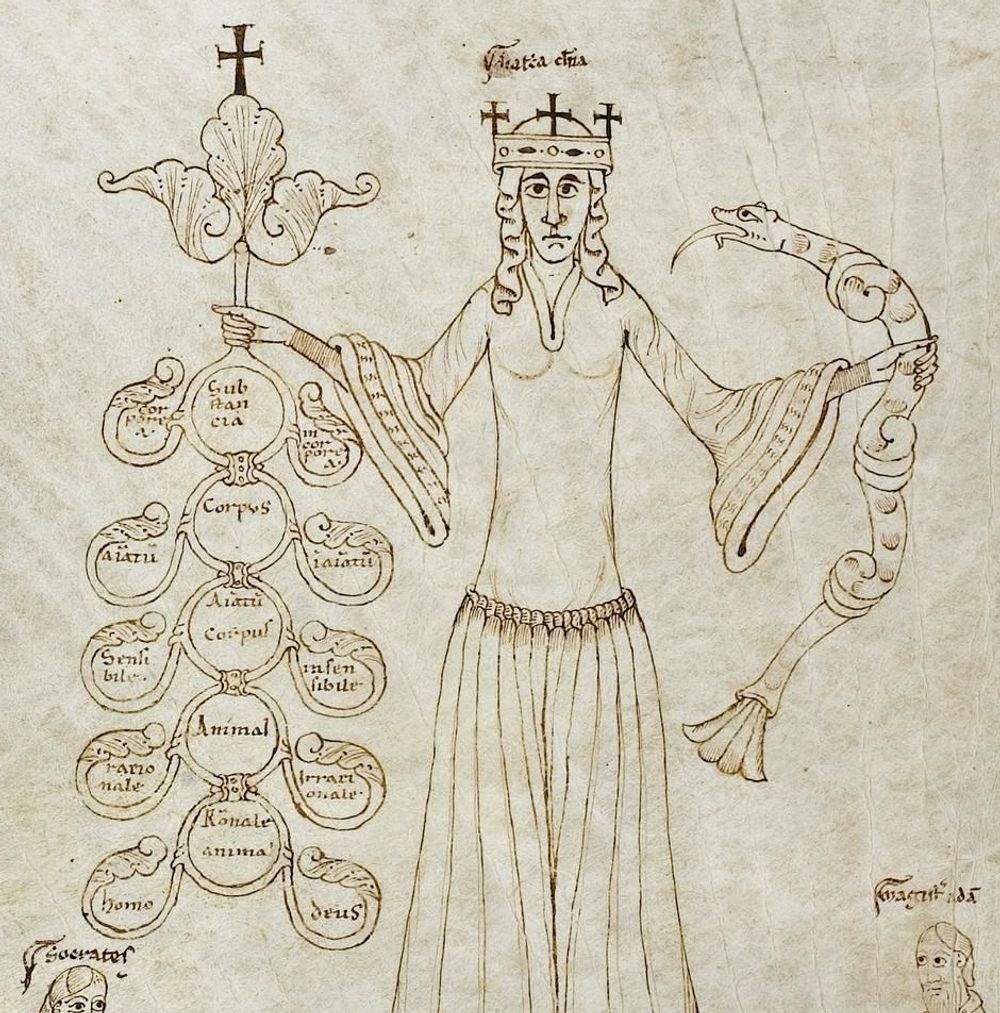

In manuscript Darmstadt, Universität- und Landesbibliothek, Hs. 2282, Lady Dialectic is depicted in the middle of the image. Above her crown, the words ‘dialectica domina’ can be read. She holds a snake in her left hand to symbolize the treacherousness of logical reasoning. In her right hand she holds a Porphyrian tree, a classic illustration of the ‘scale of being’. At the top of the tree is the most abstract ‘substance’, at the bottom the most concrete: ‘homo’, man on the left, and on the right in this case, rather curiously, ‘deus’, god.

http://tudigit.ulb.tu-darmstadt.de/show/Hs-2282

At the top of the page, the two arch-philosophers, Plato and Aristotle, are engaged in a dialectical argument, as their typical hand gestures show. On the left, Plato is seated, on the right his student Aristotle.

http://tudigit.ulb.tu-darmstadt.de/show/Hs-2282

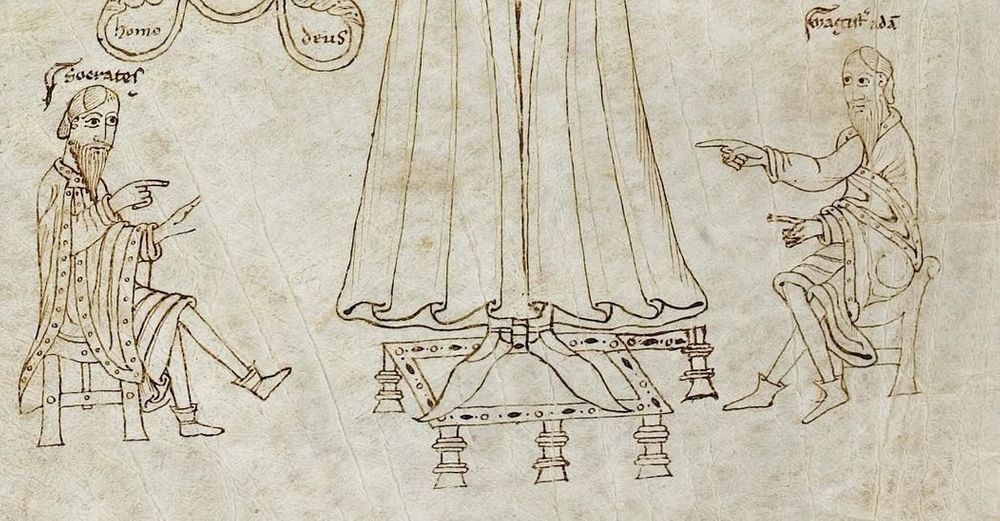

On either side of Dialectic’s feet (notice her pointy shoes), two more philosophers are shown: Socrates (Plato’s teacher) on the left and ‘Magister Adam’ on the right. It is assumed that this was Adam de Parvo Ponte, a master who taught on the petit pont (small bridge) in Paris.

http://tudigit.ulb.tu-darmstadt.de/show/Hs-2282

Logica Nova

In the middle of the twelfth century, many Aristotelian texts were rediscovered and re-translated, sometimes through Arabic translations and commentaries, especially by Averroes. Boethius had already translated many of the logical works of Aristotle, but not his Prior and Posterior Analytics, the Topica and Sophistici elenchi (read more about these texts here). With these new texts and commentaries and a new emphasis on Aristotle’s texts in the medieval university curriculum, fresh translations and commentaries flourished: William of Moerbeke, Thomas Aquinas, Robert Kilwardby and many other known and unknown medieval authors produced new commentaries. In the first decades of the thirteenth century, Aristotle’s works soon became the foundation of teaching in the Arts Faculties of medieval Europe. Logic became a fundamental subject, central to the programme.

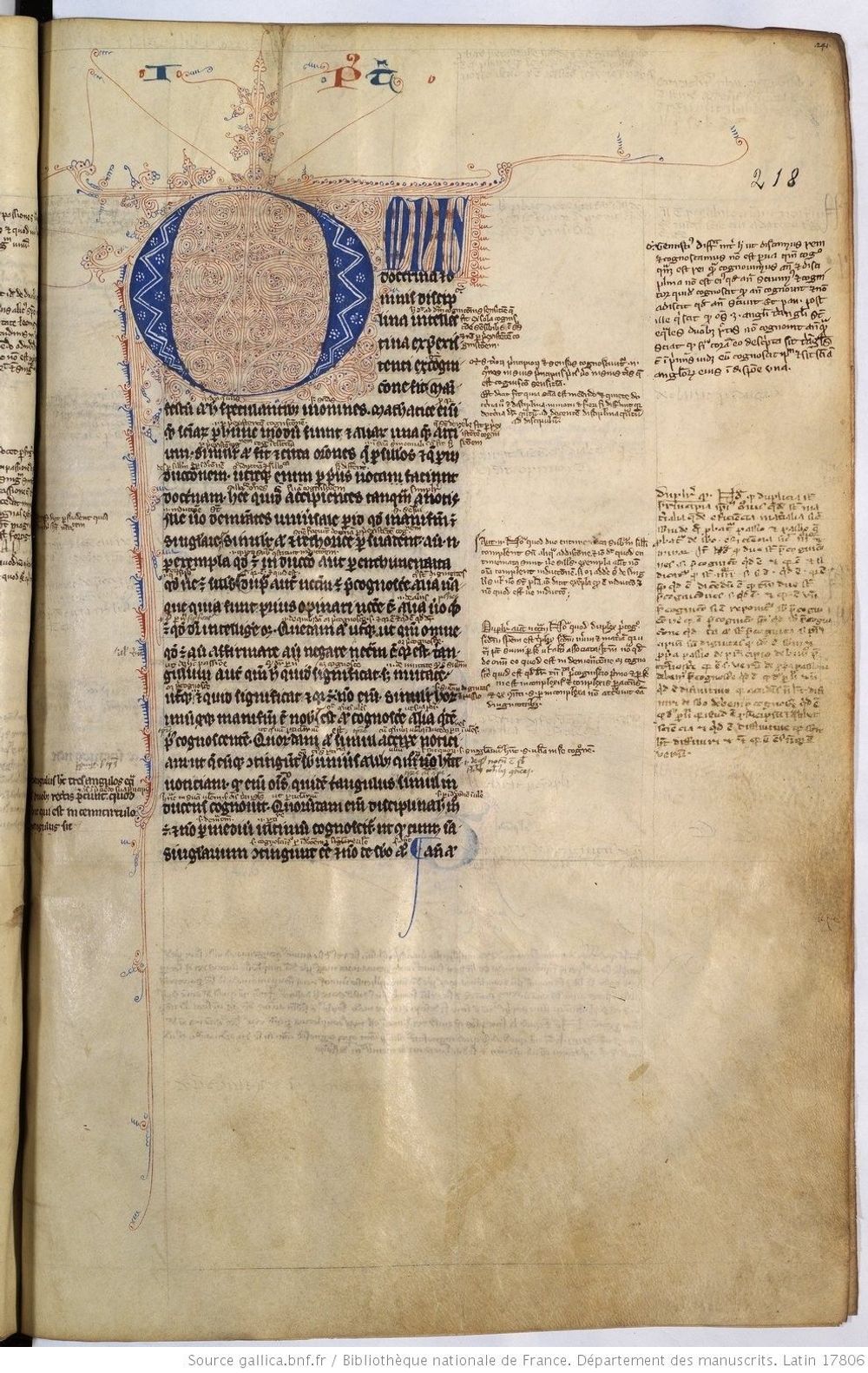

Handbooks with collections of logical texts set out in a certain format testify to this. This manuscript is an example: Paris, BnF, Lat. 17806. Here on fol. 218r we can see a column for commentary on the left of the text, and two columns on the right. The lower margin is also typically large to house large amounts of notes and comments.

https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b525053525

Sources used for this contribution:

- Olga Weijers, Le maniement du savoir: Pratiques intellectuelles à l’époque des premières universités (XIIIe-XIVe siècles), Turnhout: Brepols, 1996

- Mariken Teeuwen, The Vocabulary of Intellectual Life in the Middle Ages, Brepols, 2003: disputatio, dialectica, logica, et cetera

- Articles from the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/medieval-philosophy/) and the Cambridge Companion to Medieval Logic, eds. C. Dutilh Novaes, S. Read, Cambridge University Press, 2016 (https://doi-org.proxy.library.uu.nl/10.1017/CBO9781107449862).

Contribution by Mariken Teeuwen.

Cite as, Mariken Teeuwen, “Rhetoric and dialectic”, The art of reasoning in medieval manuscripts (Dec 2020), https://art-of-reasoning.huygens.knaw.nl/rhetoric-dialectic. ↑

Next Read:

Next Read: