The medieval classroom

Teaching in the Middle Ages1

In medieval Europe, teaching and learning were firmly in the hands of the Church. To learn how to read and write meant to learn Latin, and Latin was the language of the Bible and the liturgy. In the earlier Middle Ages, monasteries were the most important institutions for learning and teaching, and also for the production of books. In the later Middle Ages, courts, cities and institutions such as universities also became centres of teaching, learning, and for the production of books.

http://initiale.irht.cnrs.fr/decor/99412

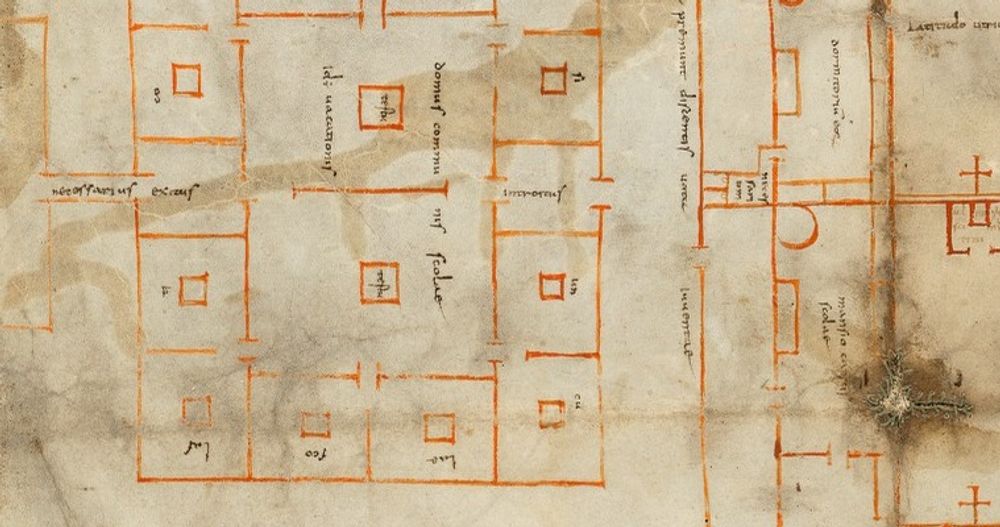

Classroom

In the early Middle Ages, and especially in the Carolingian period, children became more and more a part of monastic communities and were taught in schools housed within the walls of the monasteries themselves. In the so-called Plan of St. Gall, for example, a map of a real or ideal monastery created in the ninth century, a building is marked ‘school’ (domus communis scolae), and another one is the house of the master.

https://www.e-codices.unifr.ch/en/list/one/csg/1092

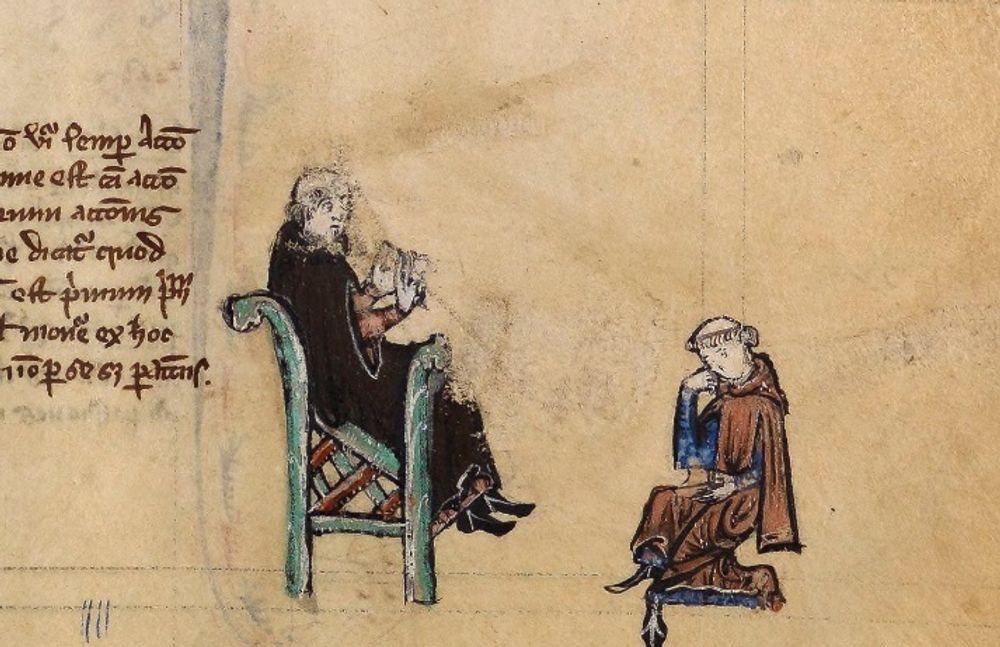

From numerous stories and pictures we learn that beating the students was a crucial pedagogical tool for the master to keep them focused. In manuscript Chambéry, BM, Ms. 27 we see a scene with a student who seems to be wearing donkey’s ears, perhaps as a punishment. The teacher is indeed looking rather stern.

http://initiale.irht.cnrs.fr/decor/35203

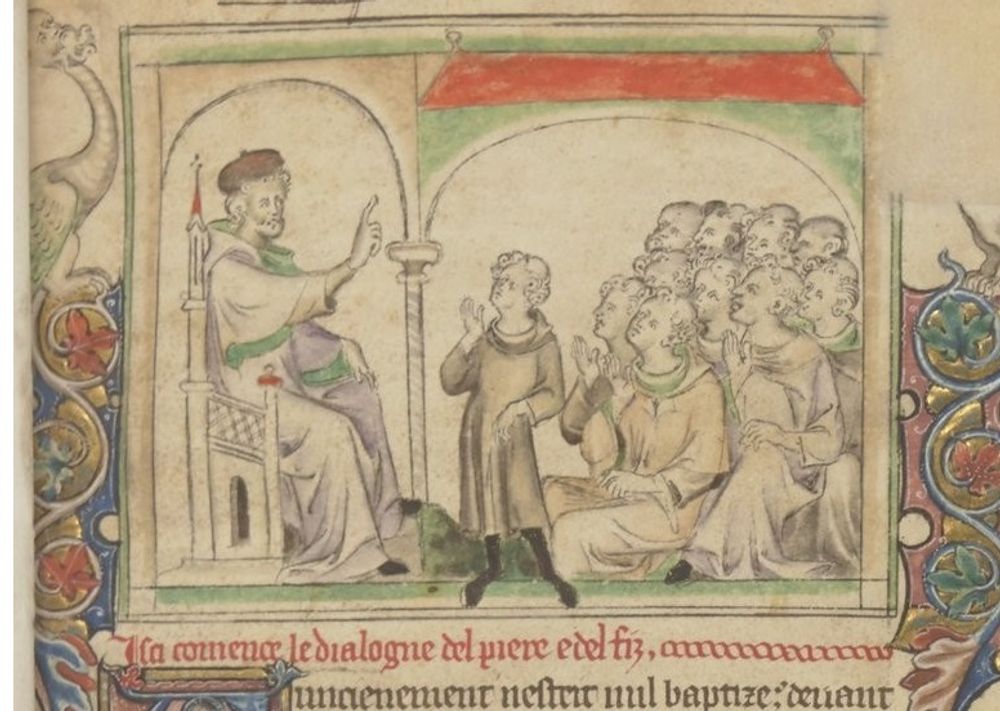

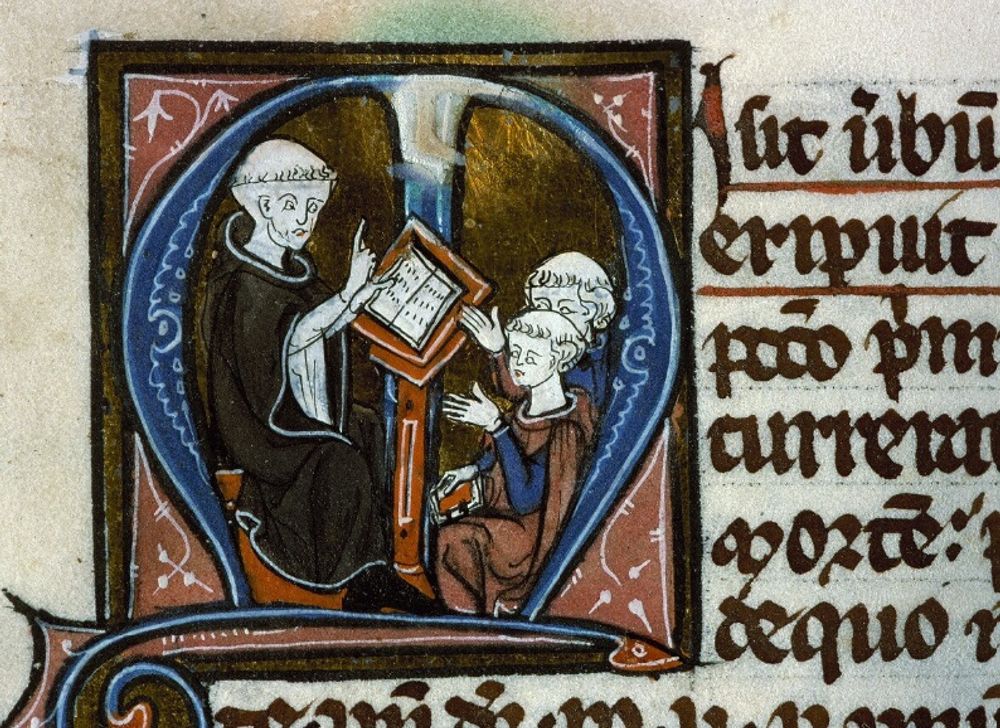

In manuscripts we find pictures of large and small classes, with young and older students, mostly male but occasionally also female. Initials in books with school texts were typically used for tiny portraits.

https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b105094193

http://initiale.irht.cnrs.fr/decor/16176

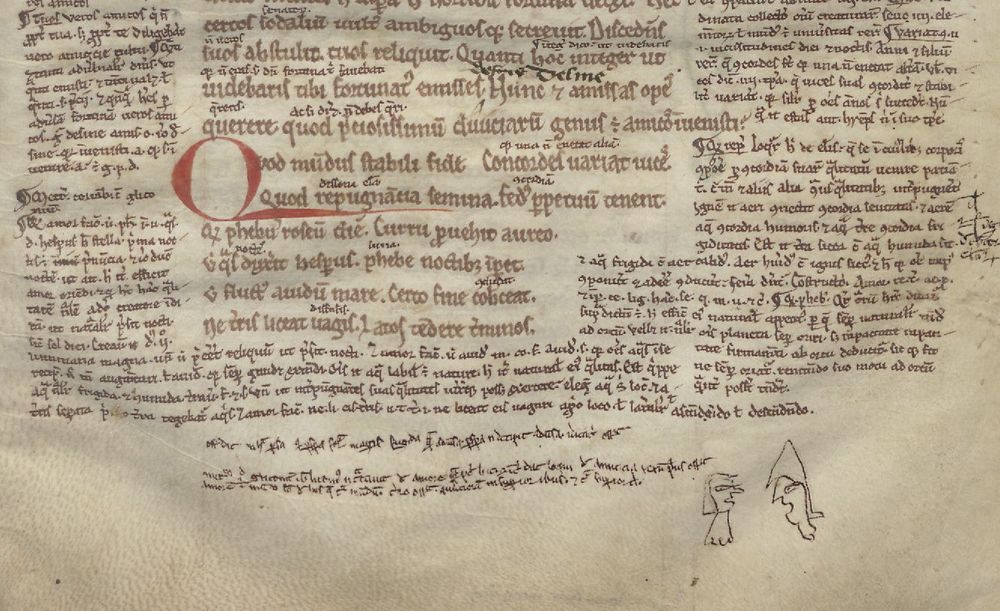

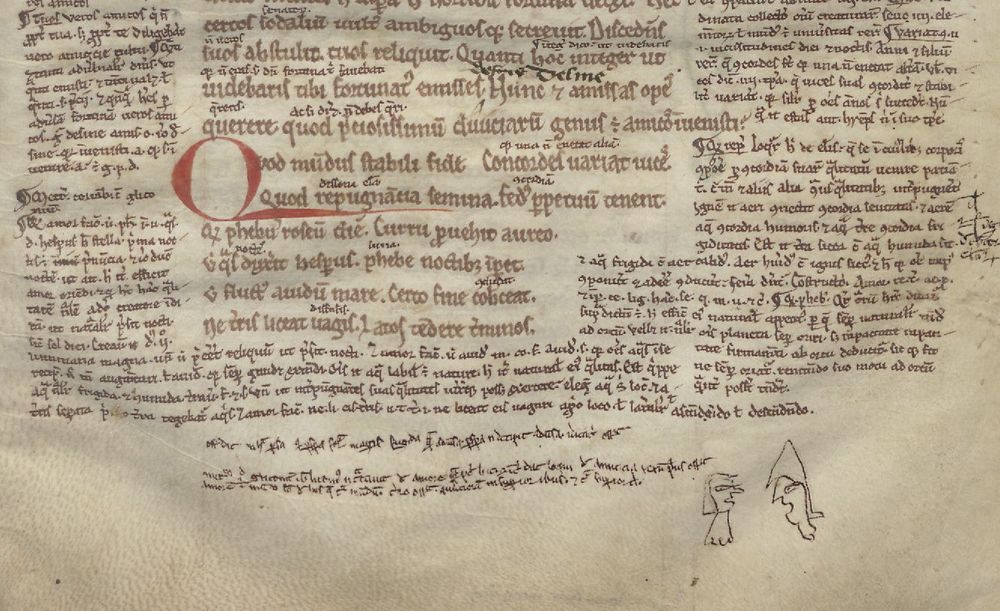

Books for the classroom

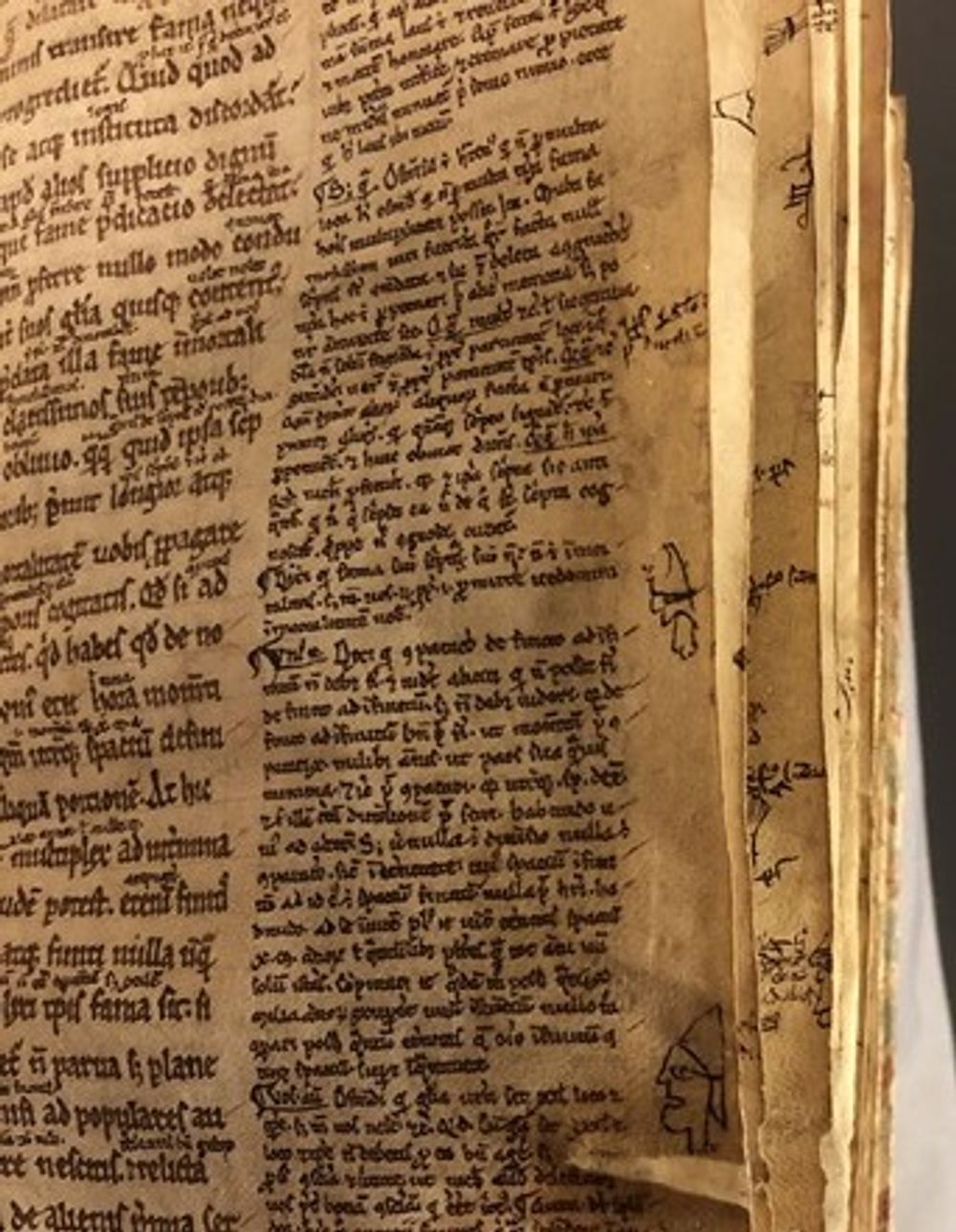

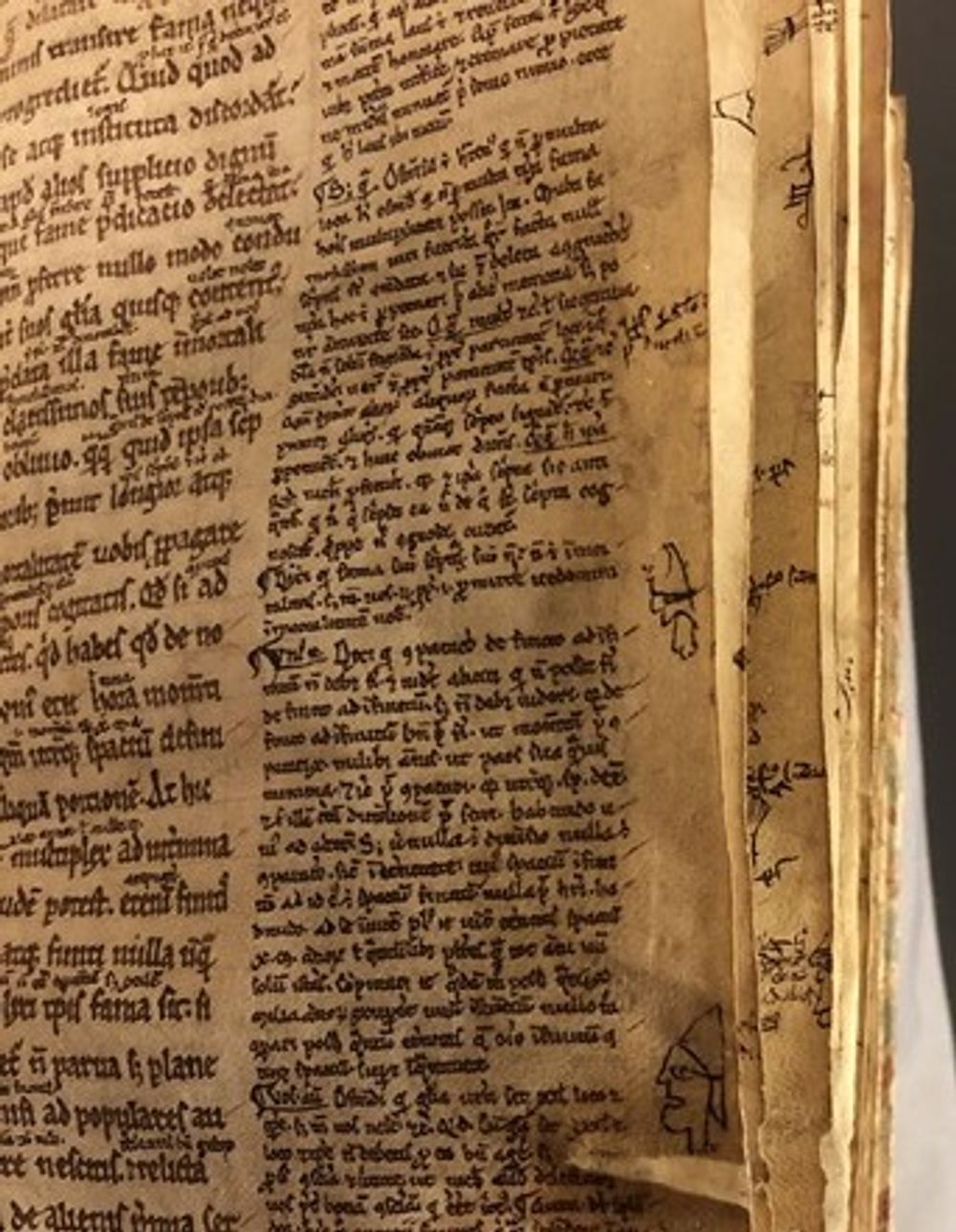

For the study of the basic topics and curricular texts, copies were made that were customized for classroom use or individual study. The traces of all this active reading and studying take many forms, ranging from wide margins, providing ample space for commentary and glosses, to a narrow format, so that the book could be held in one hand. Obvious traces, furthermore, are annotations by readers, who try to make sense of their texts with summaries, lists, signs and pointers. Portraits of teachers and students are, of course, also wonderful indications of a classroom use!

https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b525053525

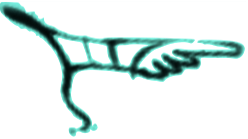

Pointers and Doodles

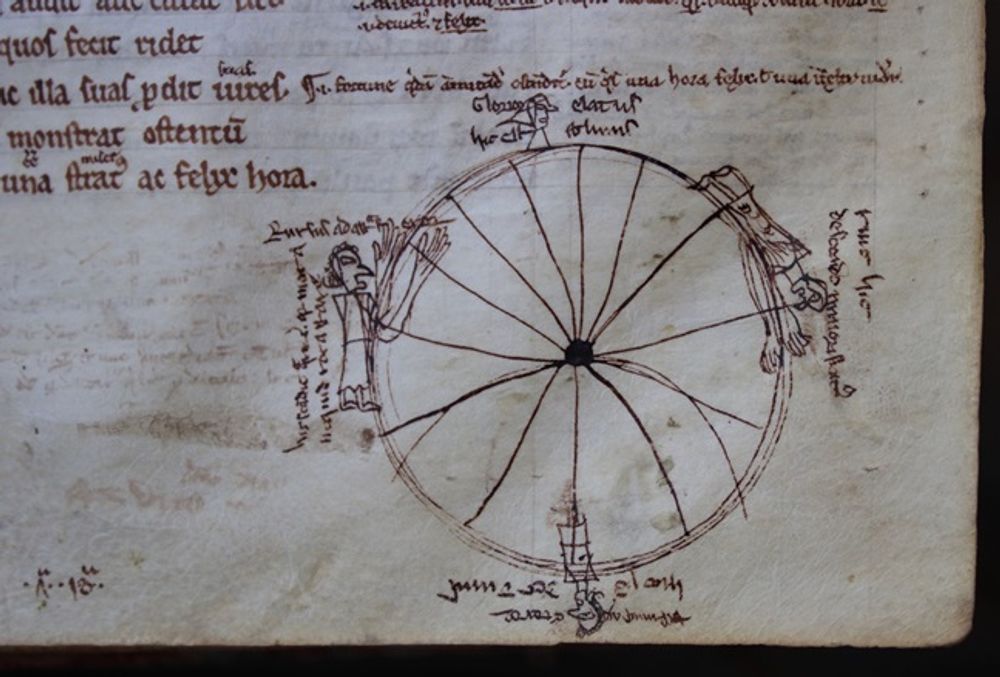

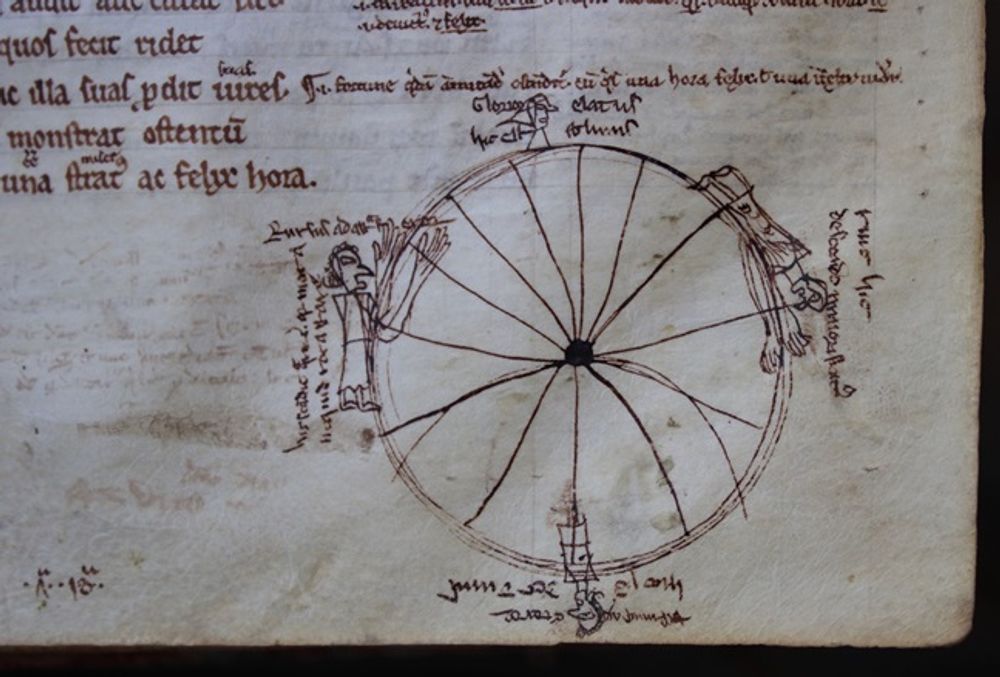

A vivid sign of personal reading is the addition of fanciful pointers and doodles that we find in some copies. Readers marked important or particularly noteworthy passages in their books with pointing hands, pointing heads or noses, sometimes even pointing feet! They also added drawings that bring a personality to these books that is astonishing. In manuscript Leiden, UB, BPL 144, with a copy of Boethius’ Consolation of Philosophy, we find many pointers and doodles added by a later hand. On fol. 10r, for example, he added a drawing of the metaphor of the wheel of fortune, which spins us up and down on the road of life.

http://hdl.handle.net/1887.1/item:2356986

http://hdl.handle.net/1887.1/item:2356986

http://hdl.handle.net/1887.1/item:2356986

Sources used for this contribution:

- D. Scheffler, “Education and Schooling”, in A. Classen (ed.), Handbook of Medieval Culture, De Gruyter, 2015, 384-405.

- Plan of St. Gall: http://www.stgallplan.org/en/index_plan.html

- E. Kwakkel, Books Before Print, ARC Humanities Press 2018, Chapter 20: “Books on a Diet”, Chapter 14: “Getting Personal in the Margin”, Chapter 15: “Helping Hands on the Page”.

- E. Kwakkel, “Doodles in Medieval Manuscripts”: https://medievalbooks.nl/2018/10/05/doodles-in-medieval-manuscripts/

Contribution by Mariken Teeuwen.

Cite as, Mariken Teeuwen, “The medieval classroom”, The art of reasoning in medieval manuscripts (Dec 2020), https://art-of-reasoning.huygens.knaw.nl/classroom. ↑

Next Read:

Next Read: