The curriculum

What was taught in medieval schools?1

In the Carolingian period (ca 780-900) a teaching programme was promoted which included first and foremost Christian learning: knowledge of the Bible and the liturgy and the works of the Church Fathers. With that, however, a whole heritage of pre-Christian and late-antique learning was also adopted into the curriculum: the Roman poets for their beautiful and complex Latin, the Greek philosophers (in Latin translation) for their systems of understanding the world. The ancient division of learning into seven key disciplines, the seven liberal arts, was also embraced by the medieval world: these became a core element.

http://special.lib.gla.ac.uk/exhibns/chaucer/learning.html

The seven liberal arts

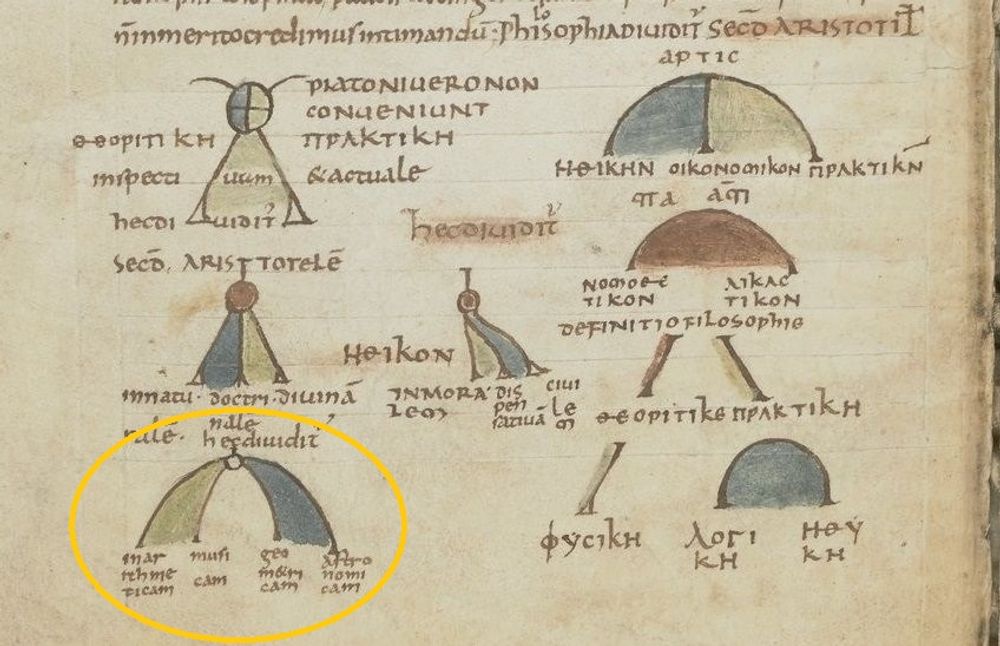

In the late-ancient and early medieval knowledge tradition, the body of knowledge (or wisdom, sapientia) was divided up into fields (artes or disciplinae) to make the whole more manageable. For the Latin Middle Ages, a division into seven liberal arts, as found in the works of Martianus Capella and Boethius, was most influential. These seven liberal arts were in turn divided into the three arts of language (trivium) and the four arts of number (quadrivium). In the image on the bottom left, several divisions of knowledge can be seen from Cassiodorus’ Institutiones divinarum et saecularium litterarum, a manual for all divine and worldly learning. In the circle you see the division of the arts of number into four disciplines: arithmetic, music, geometry and astronomy.

https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b105442152

The arts of language: Trivium

Three disciplines formed the art of language: Grammar, Rhetoric and Dialectic.

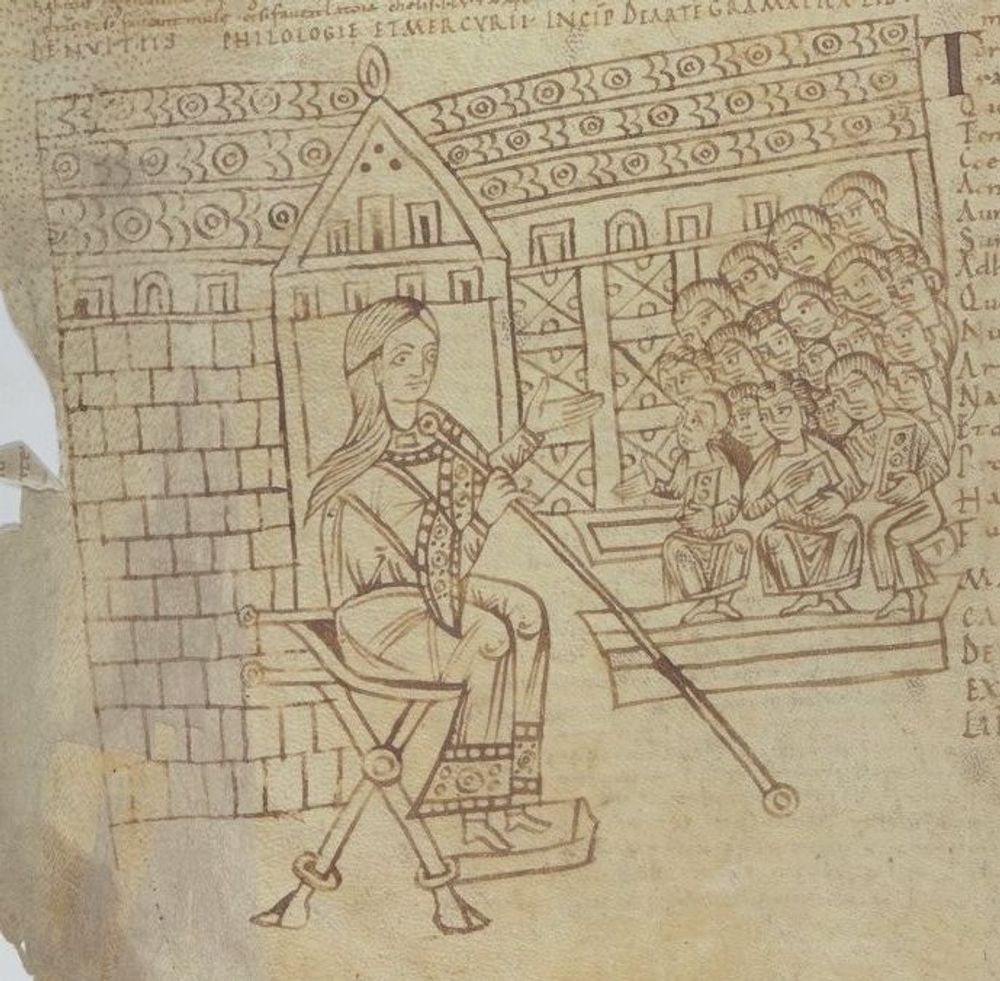

Grammar covered the basics: young students were introduced in letters, reading and writing. This introduction was in Latin, the language of the Church. Thus to learn to read or write automatically meant learning Latin. One of the basic handbooks used for a first introduction was Donatus, Ars minor. More advanced handbooks were also studied at a higher level: Donatus’ Ars maior and Priscian’s Institutiones grammaticae. In this image (Paris, BnF, Lat. 7900A, fol. 127v) we can see how Lady Grammar, a personification of the discipline of grammar, is teaching a school class. The pupils in the front row have wax tablets to practice their letters and words.

https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b10546779x

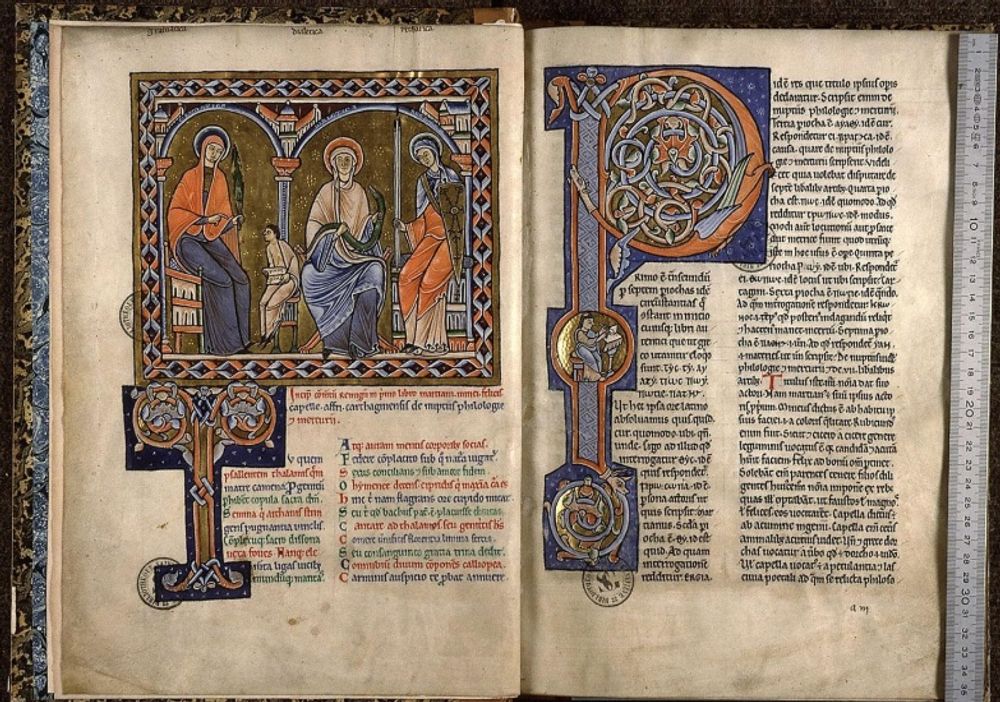

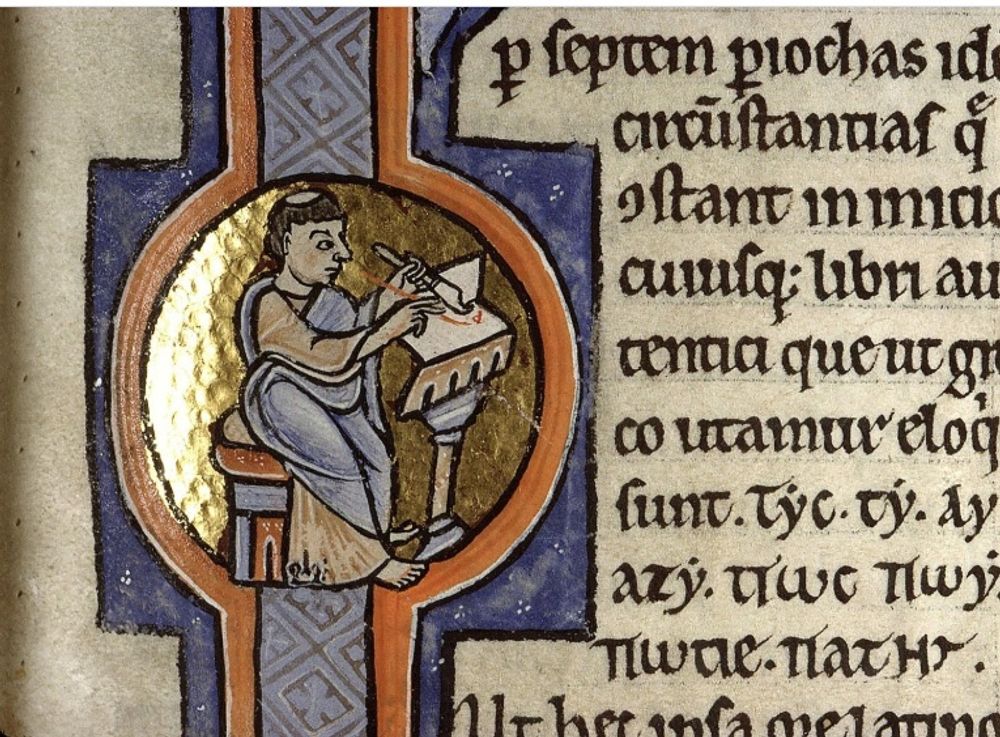

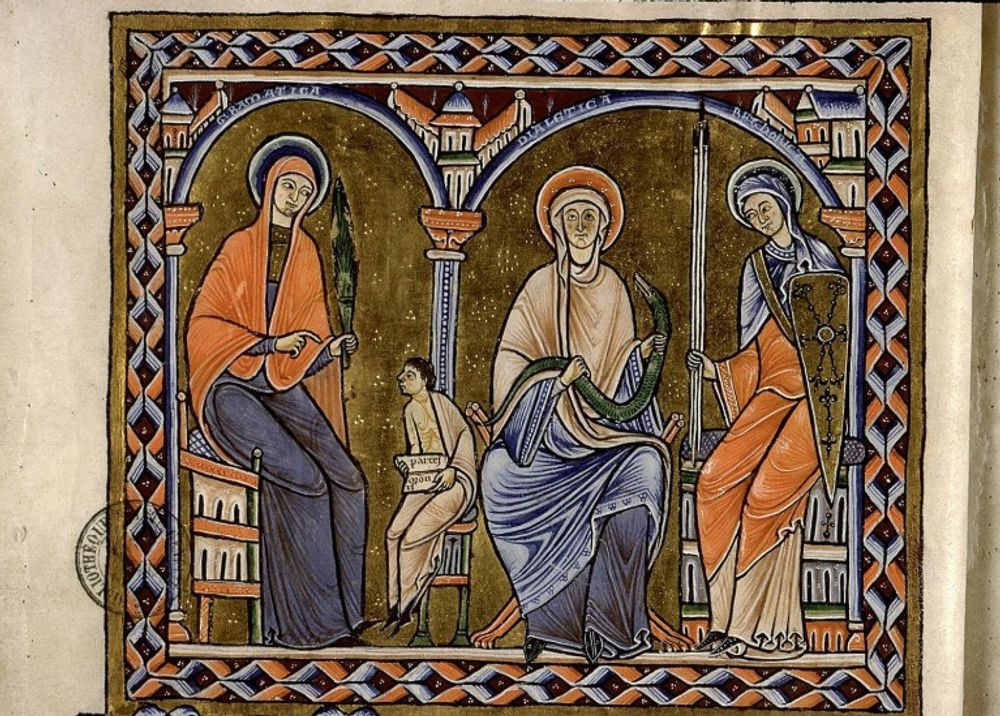

Shown below is a late twelfth-century manuscript of a part of Martianus Capella’s De nuptiis. The Trivium, personified as three wise ladies, is depicted at the opening of the text. The book was produced in north-eastern France in the fourth quarter of the twelfth century. It contains the first five books of De nuptiis, together with the commentary of Remigius of Auxerre. Perhaps the man portrayed in the initial on the right is a portrait of master Remigius himself, while he is scribbling his large commentary.

http://initiale.irht.cnrs.fr/decor/72821

http://initiale.irht.cnrs.fr/decor/72821

Lady Grammar has a bundle of rods in her hand, to chastise the student who is sitting in front of her. His upper body is already half bared to receive his punishment. In the open booklet on his lap we can read the words “partes orationis”, “parts of speech”. In the middle, Lady Dialectic is holding a snake, to symbolize the treacherousness of argumentation. On the right, Lady Rhetoric is holding arrows and a shield, symbolizing the weapons one needs to yield in a debate.

http://initiale.irht.cnrs.fr/decor/72821

Sources used for this contribution:

- John J. Contreni, “Learning for God: Education in the Carolingian Age”, in Journal of medieval Latin 24 (2014), 89-130

- Jean Leclercq (transl. by Catharine Misrahi), The Love of Learning and the Desire for God: A Study of Monastic Culture, Fordham University Press, 1961

- David L. Wagner, The Seven Liberal Arts in the Middle Ages, Indiana University Press 1986

- William H. Stahl, Martianus Capella and the Seven Liberal Arts, Columbia University Press, 1971-1977 (2 Vols.)

Contribution by Mariken Teeuwen.

Cite as, Mariken Teeuwen, “The curriculum”, The art of reasoning in medieval manuscripts (Dec 2020), https://art-of-reasoning.huygens.knaw.nl/curriculum. ↑

Next Read:

Next Read: